By Kallie Klein and Matthew Eshed

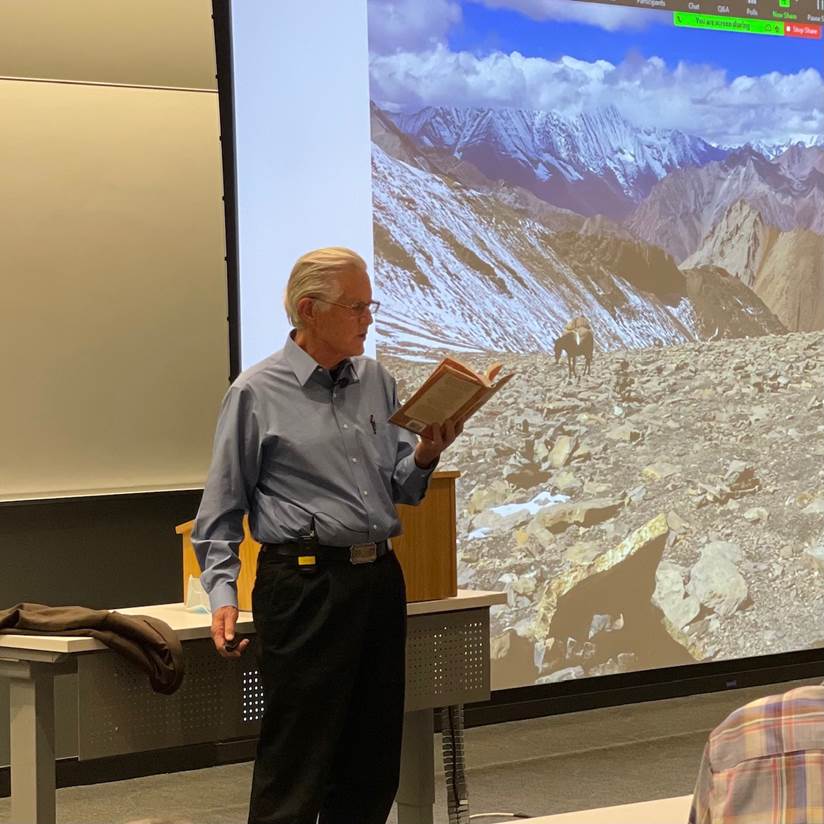

Friday, Nov. 5 marked the kickoff of the Clark School of Environment and Sustainability 32nd annual Headwaters Conference. This year’s theme was “Grief and Hope in a Changing Climate”. The weekend opened with a dramatic reading by veteran Headwaters attendee Art Goodtimes from his 2006 book of poetry titled “As if the World Really Mattered.”

This was an early indication that a unique Headwaters culture has developed over the 30 years. Interim Clark School of the Environment Dean Dr. Melanie Armstrong introduced the conference, reminding us that the headwaters in which we live is a place of art, community, as well as “vague ideas”, and “romantic visions.”

She also reminded us that the conference itself is a vision 30 years in the making, and that “we have a great gift in the valley.” Dr. Armstrong blessed the conference, saying “may tonight be loud and memorable.” ENVS professor and Integrative and Public Lands Management Director Dr. Micah Russell directed the conference this year.

The Keystone Address was given by author and conservationist William DeBuys, centering on his “accidental trilogy” books: “A Great Aridness,” “The Last Unicorn,” and “Trail to Kanjiroba.” In the presentation titled “Navigating the Rivers of Our Future – Have You Got the Right (Emotional and Ethical) Gear?,” DeBuys recalled stories from his journeys conducting research for his respective books in the American West, the forests of Laos, and the Himalayas. He reflected on environmental grief free from cynicism, despair, or apathy, and his journey while dealing with these emotions.

DeBuys shared that even with all the environmental tragedy he saw across continents and expeditions, he still sees hope and a chance to heal our planet, even if we cannot completely save it. How can we cope with our feelings about the natural world and our future? The following passage from “The Last Unicorn” reflects DeBuys thoughts:

“Off to the side from the rim, I saw this: a white horse part way up a dune at the bottom of a cliff. The dune was corrugated with sheep trails, thorny inedible green shrubs stipple the sand, I couldn’t imagine what that poor horse was finding to eat. The land was battered, almost barren, and yet I could not take my eyes from the view. A bright white horse amid emerald shrubs on purple-red sand. The color, the contrast, the unadorned solitude of the horse. All the elements of the tableau converged in a way that was more than pretty, more than merely picturesque. I felt stunned, and then inspired, although I could not immediately say how. I snapped a dozen photographs sensing that the horse and the land on which it grazed answered a question I had not known how to ask.

Months later I realized the photographs expressed something I had failed to grasp in the Lao forests. The realization was almost mathematical. It said that Earth’s beauty is inexhaustible; even where the world is most diminished, beauty remains. The forces that erode the life of the planet can reduce but not eliminate that beauty, for beauty is intrinsic to this planet. Or if not to the planet, then to the way we sapiens have evolved to see it. And the beauty belongs to us; it inheres also in us and it needs to be conserved in us too, for we are part of the planet… If beauty is infinite then the need, and for some of us, the obligation to defend such beauty is also infinite. This obligation will last as long as beauty lasts, and so it will have no end. And that kind of work, serving that duty, that work can be meaningful and meaning in life is something we all hunger for.”

DuBuys’ most recently published book, “The Trail to Kanjiroba: Rediscovering Earth in an Age of Loss” (2021), discusses an important takeaway from his journeys: “every day a yatra (pilgrimage).” He explains this lesson by saying “on a pilgrimage you can’t go missing, you have to show up and be present, and you have to be clear about your intentions.”

This lesson and many others came through traveling around remote Himalayan villages with the Upaya Zen Center Nomad Clinic, a Santa Fe-based Buddhist center that traveled with doctors and limited medical supplies to provide healthcare services in the backcountry. DuBuys’ experience with the local Sherpas and guides, the healthcare providers, and the villagers provided him with the life lessons he shared with us at Headwaters. He implored us that “life is a pilgrimage,” and invited us to build our own personal “arks,” as in refuges, wildlife corridors, healthy soil, and other alternatives to polluting and ecologically disruptive ways.

After all of his journeys, DuBuys’ guidance on carrying grief is this: “the right way to carry the grief is the right way to walk,” or “the right way to walk is the right way to carry the grief.” He now sees that social-ecological relations can take on qualities of hospice; a process that involves sitting with the dying, letting them live out the remainder of their lives with the highest comfort and purpose available to them. Outdoor movement for mental health and healing is not a new concept for this Mountaineer community — and perhaps the spiritual aspect will also be familiar to our readers.

Following DeBuys keynote, the conference continued on Saturday with talks and an ensuing discussion between authors Lynne Quarmby and Ayja Bounous, hosted by the Director of Western’s Nature Writing program, Laura Pritchett.

Dr. Quarmby is a scientist and author and is currently working as a professor of cell biology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. She gave a wonderful talk about her book “Watermelon Snow: Science, Art, and a Lone Polar Bear.” Dr. Quarmby described how global warming science increasingly took over her attention, how it inspired her to run for Canadian Parliament in 2015, and how these actions were all steps on her “path to healing.”

Her exhaustion was not only burnout; it was failure to grieve, a failure to feel what was lost. Through learning to appreciate sorrow and pain, she initiated a new scientific research program, which led to her watermelon snow study, pairing climate change with microbiology. Dr. Quarmby brought a different angle to the table by sharing that the fossil fuel industry has invested significant money in controlling the narrative, and implored the audience to take the narrative back.

Avid skier and author Ayja Boumous shared from her book “Shaped by Snow: Defending the Future of Winter.” She opened with a statement regarding the effects of global warming that the Mountain West has experienced in the last few years. Accompanying this was an observation that the ski community often talks about climate change during low snow years, but not during ‘normal’ years.

Some people leap from grief into action, and some don’t, instead being consumed by down-ness. Boumous shared solidarity with those of us who recognize this, saying “climate grief is common – you are not alone.” In a particular moment of creativity, Ayja shared her perspective on harnessing the oscillations of grief, like we harness the oscillations of water, wind, and sunlight to generate energy. And finally, Ayja shared a call to action: to meet once a week, that great things come when people meet regularly around a common cause.

Both Boumous and Dr. Quarmby beautifully discussed how to cope with grief and eco-depressions, sharing examples of how they heal and how they have helped others to heal; how to balance your anger and depression with the motivation to continue the climate fight. As authors, they both energetically encouraged writing. If you are writing a book, Ayja says “keep pushing!” Lynne described writing as “facilitated processing,” as a way to “go deeper into meaning,” and a way to “shift the zeitgeist.”

Dr. Quarmby also recommends writing letters to the editor and op-eds as tools for action. For their closing remarks, they were both asked to describe snow. Boumous’ description entailed a “joining of sky, hydrogen and oxygen bonds, miraculously falling around us….snow defines our planet, and is a wonder of the world.” Dr. Quarmby views it from the microbiological lens, that snow is “ephemeral, yet a place for communities of microorganisms,” and that the microorganisms she studies exhibit “cooperation for life to survive.”

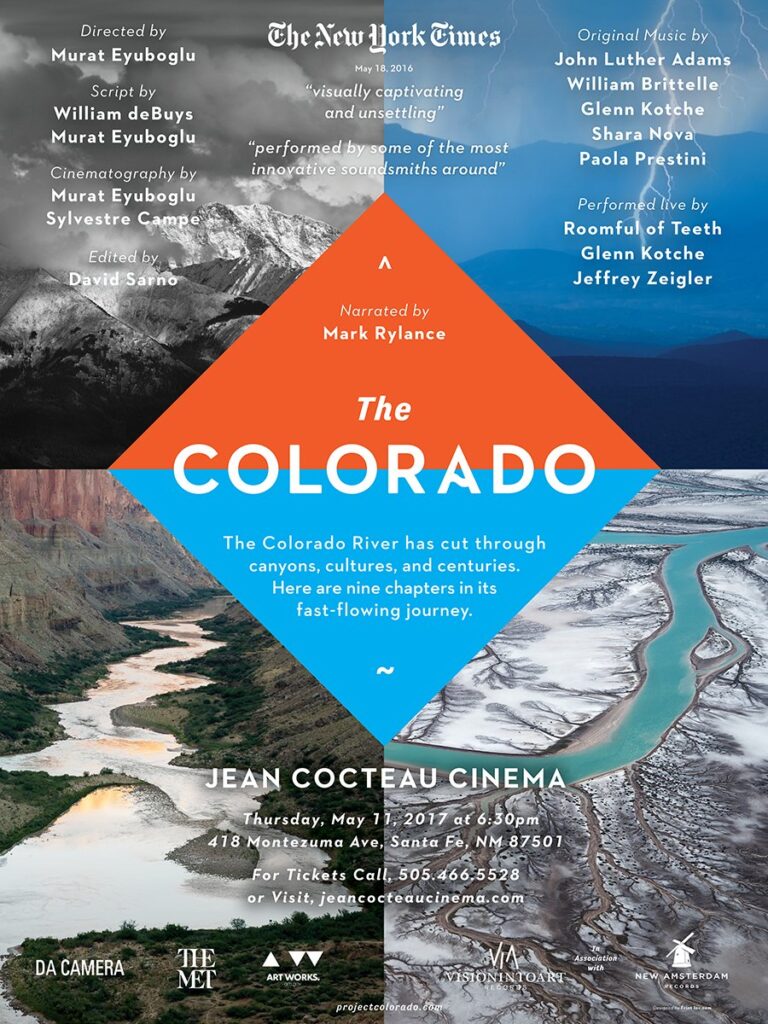

Saturday afternoon brought the conference to a close with the showing of two movies. “Wild Climate” (directed by Peter and Virginia Sargent) and “The Colorado” (directed by Murat Eyuboglu; co-written by Murat Eyuboglu and William DeBuys). “Wild Climate” focuses on stories from people living in the rural west and how climate change has been impacting their livelihoods.

They travel from Texas all the way up into Montana, stopping in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Idaho interviewing locals and telling their stories. In the film, they visit an outfitter in Idaho who is outspoken about climate change, as his job requires protecting and conserving the backcountry, and thus climate change directly affects the backcountry guiding industry.

“Wild Climate” also brings us into conversation with Justin Reiter, a pro snowboarder in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, who decisively states that climate change has a drastic effect on people’s livelihoods in small mountain towns. His perspective, echoed throughout this film, is that elected officials are not doing enough.

The film also delved into the lives of the family behind Purple Sage Farms in Middleton, Idaho, who remembered a recent big snow followed by a big rain event that destroyed their greenhouses and wiped out some of their crops. The more extreme, “vicious” weather events motivate them to take action while facing “a really gnarly climate future.” The family implores the audience to “talk to people, get the federal government to recognize the emergency, and step up in action.”

Wild Climate board member and environment-focused branding and marketing expert Rob Duray was present on Zoom for questions. Duray shared that “folks on the land in the West are not represented in the climate movement.” To what scale this is true is difficult to say, but it is a call to awareness nonetheless.

In response to a question about affecting the actions of the federal government, Duray had this to say: finding common ground is hard work, there is no magic or silver bullet, you have to build influence via organizing, and elected officials will eventually listen. If Senators from the West come together to address climate change, they can wield considerable collective power. In Duray’s opinion, the West is a great place to talk about climate change, since the changing climate’s impacts are felt as much, if not more, than the rest of the country.

“The Colorado” tells the story of the Colorado river with a modern score and stunning imagery, featuring music from leading composers. Director Murat Eyuboglu shares a bit of his genius regarding the audio and visual aspect of the film, saying “extralinguistic qualities can be a foundation for communities.”

Covering everything from European exploration, the dam-building era, including the unfortunate accident that created the Salton Sea, and the current impacts of climate change, the film spans hundreds of years in time and a vast topical scope. It is a true journey into the West and a story about the adaptability of nature, split into nine distinct chapters, including: “Myth of Origins,” “An Unknown Distance Yet to Run,” “Shimmering Desert, and “The Colossus.”

Within the auditory experience of violins and flowing water, we are reminded that the river “crashed and howled, and sometimes it murmured. Over 12,000 years, hardly a blink in the life of the river.” Visually, we were provided with images of petroglyphs cut with images of animals today: elk, coyote, bison, bighorn sheep, as well as gnarled trees, storms, precipitation, lightning, and a full moon. The music is always epic, harkening to the director’s career beginnings as a music video director.

The auditory and visual aspects, as well as the story-like structure softens the impact of learning about the dried-up Colorado River Delta in Mexico and how 85% of America’s winter vegetables are grown in California’s Imperial Valley, which is irrigated from the Colorado River. Elders of the Cucupah people, literally “People of the River,” remember what was once a plentiful estuary and fertile delta where fish were plentiful, is now a barren, dusty lakebed. We are reminded that “people have forgotten to ask what progress costs the earth and the future.”

The conference ultimately instilled a sense of hope in this time of environmental crisis, reassuring that we don’t have to fix everything, and simply doing what we can is enough. In the words of William DuBuys, we are called to “navigate the river of your future with conscious intent,” and from Ayja Bounous, we are invited to “inject everyone with empathy.”

Between these great authors and thought leaders is great potential. In the middle of his talk, DuBuys mentions a list of slogans he has derived from his travels and explorations. They are as follows:

“Care over cure; avoid attachment to specific outcomes; optimize the present but also recognize and honor endings; strong back, soft front, by which I mean you have to be ready for the hard stuff but not by shutting out the people or other beings entangled in it… the real breakthrough turned out to be something else. something less in the mind and more in the heart. I need to make peace with sorrow. My delight in the beauty of the natural world coexisted with grief at its destruction. These emotions were like cell mates who cannot get along. They dwelled in my head and in my heart and their constant argument created a moral ache. I had to either dispel that ache or learn to live with it.”

The conference concluded under the theme that these feelings are normal and make us all the more human; without the humility of understanding our limited agency there will be neither care nor cure.

Links to additional educational resources surrounding the films screened at Headwaters: