This story is part one of an ongoing ENVS Project Series highlighting Clark Family School of Environment and Sustainability (ENVS) projects, and their relations to the broader environmental movement and to the Gunnison Valley community.

As part of the Master’s in Environmental Management (MEM) program, students must complete 600-hour projects in collaboration with sponsoring organizations, which can be nonprofits, government entities, or private companies. Second-year MEMer Alex Stach wanted to pursue a project which integrated his outdoor passions, which include snowboarding, splitboarding, and fly-fishing.

In the MEM program, students pick between three designated emphasis tracks: Integrated and Public Land Management (IPLM), Global Sustainability (GS), and Sustainable and Resilient Communities (SRC). Stach is in the IPLM track, and in the fall of 2020 was on the lookout for a project which would allow him to garner experience working with federal agencies.

Filling the Lead Researcher role for the Winter Data Collection Initiative through the Center for Public Lands (CPL), a resource, research, and advocacy hub under Western, Stach located such a project. CPL is run by Dr. Melanie Armstrong, a former National Park Service (NPS) employee and the Interim Dean of the Clark Family School of Environment and Sustainability.

CPL’s mission statement reads: “The Center for Public Lands at Western Colorado University is a training and resource center connecting students, land managers, and communities in a collaborative manner with public lands and waters.” CPL’s dominant focus areas include research and project development, experiential, place-based education, and public engagement.

The Winter Data Collection Initiative, as it is formally known, began in 2016-17 with a pilot year, but the 2017-18 winter was the study’s first official data collection year, under the direction of former MEM student Luke Shaw. The data from the winter recreation survey is vital to a number of different stakeholder groups, including user groups like Silent Tracks (quiet uses like skiing and biking), Gunnison County SNO Trackers (snowmobiles), and Save the Slate (environmental advocacy), as well as federal agencies like the U.S. Forest Service.

Other local groups, including the Crested Butte Avalanche Center (CBAC), use the data to see which areas are experiencing high usage, and tailor their forecasting and education efforts accordingly. Local search and rescue groups might utilize the data to coordinate readiness for anticipated rescue efforts, and the Town of Crested Butte and CB Land Trust (CBLT) use the study data to inform trail maintenance, parking lot infrastructure needs, and broader recreation management strategies.

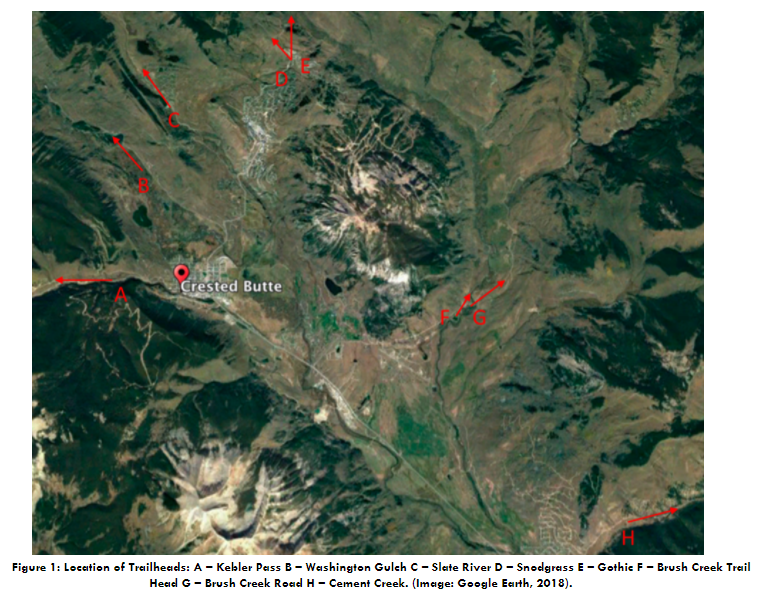

The winter recreation study utilizes eight trail cameras to monitor six distinct trailheads and generated about a quarter-million total images in 2020-21 representing about 44,000 distinct users. Managing the cameras is an iterative process throughout the winter, and one that is dominated by trial and error: checking the batteries, adjusting the cameras for snow levels, working with a private landowner that graciously hosts one of the cameras, and ensuring aggressive wildlife (or humans) have not damaged or tampered with the equipment.

With the cameras successfully in place, Stach and his trusty research assistants come out to collect the data around once every 7-10 days, ensuring everything is in working order and swapping out the memory cards. Stach often aims to cap off a productive day of making the camera rounds with some backcountry recreation of his own.

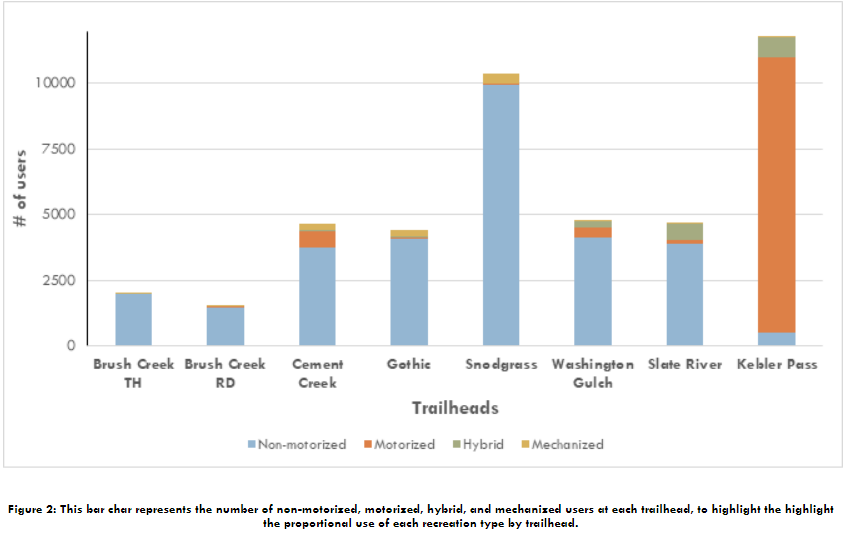

Back at their computers, Stach and the study’s assistants (typically Western undergrads) sort the users into four groups: motorized (predominantly snowmobiles), mechanized (bikers), non-motorized (foot traffic and all forms of skiing), and hybrid (motorized users bringing in equipment to ski, snowboard, etc).

“We used to have a much more detailed categorization process, and we would look at: are they cross-country skiing, are they backcountry skiing, are they walking their dog, so we don’t do that anymore, it’s just too much,” says Stach. He notes that among the more than 200,000 images are some cute fox photos, a lot of dogs, a possible mountain lion sighting, a woman having a rough ski day with her dog, and a slew of recreationist selfies, including fellow MEMers.

The Forest Service is in the midst of revising the combined Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison (GMUG) National Forests management plan, a once-every-several-decade process with big ramifications for recreation users, extractive industries like logging and mining, and the future of the region more broadly via decisions on grazing, water resources, and other hot topics.

The GMUG revision includes planning for winter travel and recreation planning. These decisions could have huge impacts on recreation opportunities and access, with particularly large ramifications for snowmobilers and other motorized recreationists. Motorized recreationists could lose out on roughly 90% of their current usage area should Alternative D, the most restrictive option that would designate the most wilderness and special management areas (areas which often restrict certain user types), be chosen.

Of the four alternatives on the table, Alternative A calls for largely maintaining the status quo, while B and C favor blended management and active management, respectively. The public comment period for the GMUG revision closed in Nov. 2021, and now the forest service will take time to analyze public comment into 2022 before making a series of final management decisions, which will likely come down in 2022 or 2023.

Stach notes that the bulk share of motorized usage takes place on Kebler Pass (about 10,000 of Kebler Pass’ roughly 10,500 users were motorized, largely in the form of commercial tours), and recreationists will often utilize snowmobiles to access safer terrain for non-motorized recreation off the pass, like backcountry skiing, a point that Stach sees as valid in an era of heightened avalanche concern. Last year, 12 Coloradans died in avalanches, a fact largely attributed to increased backcountry visitation.

Stach notes that both Emmons and Gothic, two of the closest mountain options for recreation based out of Crested Butte, carry high avalanche danger. Users looking to avert this danger and still ski in the backcountry often turn to snowmobiles to expand their range of recreation opportunities while mitigating hazards.

Stach believes that Kebler Pass is firmly off-limits to losing motorized recreation access, but knows that the winter recreation study will help inform what secondary or tertiary areas are also of significance to motorized users, and should not be axed “cold turkey”, as he terms it.

Snowmobiles are often a point of contention due to their outsized impact on wildlife, high noise profile, and other factors that irk various other types of recreationists, as well as conservationists. Another issue at hand is the Slate River trailhead, which sees the second-most motorized usage behind Kebler Pass, and the parking lot is not as well suited to handle the excess traffic load, leading to some trailer-based traffic jams.

While Stach notes that there was a significant jump from 2019-20 to 2020-21 in total usage and average usage, he cautions reading too much into the spike. One caveat for the findings is that Stach collected substantially more data than in previous years, having the cameras in position for longer amounts of time. “The reason I was able to collect more data is because they have the methodology figured out,” notes Stach, referring to research minutiae such as camera placement.

The honing of research tactics could explain a portion of the total usage bump, but would not explain the increased daily averages. Covid-19 and a nationwide uptick in outdoor recreation as refuge is also a factor, as is the increasing popularity of Crested Butte and the surrounding backcountry region, buoyed by pandemic concerns and reflecting a broader trend to escape the crowded Front Range and head into the backcountry.

Stach notes that the first year of official data, 2017-18, is the second highest in the four years of completed study. He adds that during the 2019-20, the lowest year on record thus far, research was truncated with covid lockdowns and travel restrictions, skewing data from March 2020 until the seasons’ end.

Another huge factor: total snowpack and snowfall events across research years. Western Statistics Professor Zackary Treisman aided the recreation study with their four year study report, cross-referencing snowpack data with recreation data in the statistics program R Studio. The findings were largely predictable, and suggest that higher snowpack years correlate strongly with increased recreation. News flash: winter recreationists love fresh powder. One interesting finding was that massive dumps of snow at avalanche-prone areas often leads to a temporary decline in recreation activity as users avoid avalanche danger.

Stach is curious to see if the covid recreation bump will hold or even increase this year. “I think also the industry’s just growing, more and more people just want to get out and backcountry ski,” he says, citing technological increases in gear which allow people to travel farther faster, dropping gear prices, and Crested Butte’s burgeoning popularity as a backcountry hub.

Looking ahead, Stach will shut down the cameras sometime in mid-spring. April 15 has been the designated cutoff point in the past, but he is curious to potentially extend the research season to May 1, as the best (and safest) part of the backcountry season often arrives at the tail end of winter, which he would like to capture.

Beyond his anticipated graduation in May 2022, Stach would love to find the proverbial “dream job”, working on issues of winter recreation management, incorporating snow science, integrated land management skills from Western, and his personal love for winter recreation.

Alex: let’s hope you find that dream job next!