In this series, we will trace the history of the Top o’ The World, and Western itself, through the recollections of the student newspaper’s former editors.

“I was very politically naïve, and I was just in the job because I was having a lot of fun, and one night I was down at the Red Dolly Pub and someone says: ‘Hey, Cunningham, you’re about to be impeached!’”, recalls John Cunningham, the editor of Top o’ the World for the majority of the 1967-1968 year. “I still have got the paper with the votes pro and con on [my own] impeachment.”

Cunningham was elected editor of the student publication after working as both a writer and a business manager for the student paper beginning in 1965.

He remembers his first piece, a feature story for Etcetera — the student magazine published in concert with Top O’ the World — recapping Winston Churchill’s life after his passing in January 1965.

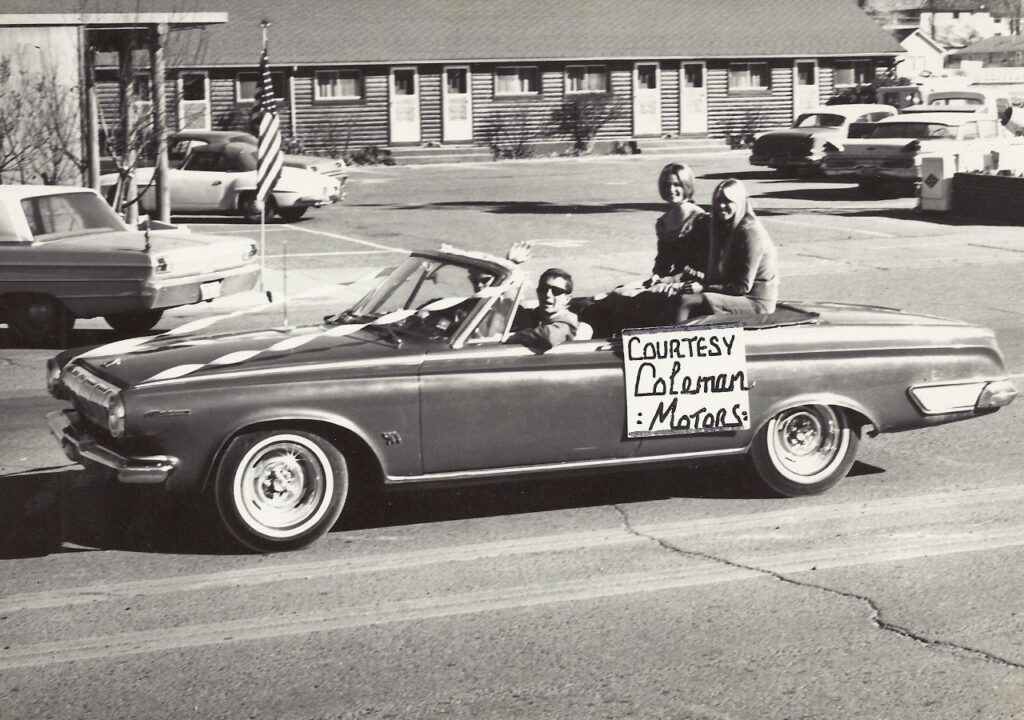

In his earlier role as business manager, Cunningham would ride his bike around town picking up the ad copy from Mario’s Pizza and other businesses around town.

“It was a pretty nice job until my bike got stolen, then my roommate wrote a searing editorial about the poor business manager and how his bike’s been stolen,” recounts Cunningham.

He notes that without a journalism major or relevant coursework offered at Western (a journalism minor would be instituted later), the paper’s editorial standard was not always the highest during his tenure.

His roommate at the time submitted political cartoons, and Cunningham says it was not a rare occurrence for articles poking fun at professors for their real or perceived misbehavior to be published.

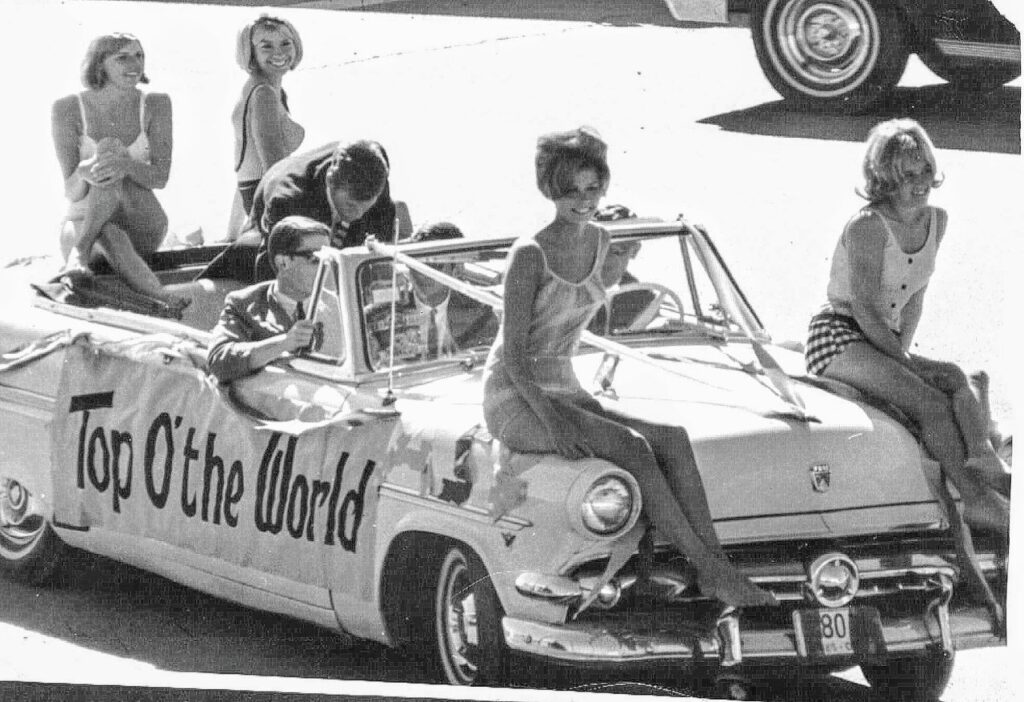

On the sports beat, fellow student Mike Taylor providing consistent coverage during a period when Western’s football team was consistently winning the RMAC Championship, including a parade of titles from 1963 to 1966.

For his part, Cunningham wrote a number of features on the research going on at Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory (RMBL), the research laboratory in Gothic, Colorado up in the mountains beyond Crested Butte that maintains an ongoing partnership with Western.

Navigating campus politics

In those days, the editor was selected by what was known then as the Associated Student Body (ASB), which is now called Student Government Association (SGA).

“It was a little like succession to the crown, because generally the business editor became Assistant Editor and [then the Editor],” says Cunningham, who assumed the editor’s chair after Dick Montrose.

In hindsight, Cunningham recognizes the inherent folly of selecting a position like editor by a vote. “What happened was the people who chose me as editor were not the same people who were there the next year,” he explains.

With a shift in campus politics, Cunningham found himself ousted, and later pushed for systemic change to the process.

“I started proposing a committee that would be appointed with the job of selecting an editor not based on their popularity … [but] on their talents,” he adds.

Back then, the Quigley Club and the Luftseben Club, a pair of social, political, and community service clubs on campus, were constantly battling for influence and status at Western.

Cunningham believes he had run afoul with the Quigley Club members by hanging around with the more “elite” Luftseben crowd, who had earned themselves a reputation for being wild partiers.

He recalls asking a member what the deal was with the Luftseben Club. The member replied, “’Our job is to party with the elite of Western State College,'” relays Cunningham. “That’s a direct quote … I would say better than half the kids who belonged to that club were from back east … they were party people.”

Because every club, fraternity, and organization at Western was granted one vote within the ASB, there was a tendency to practice vote “stuffing” by formulating new sanctioned campus organizations, each of which received one vote.

Properly incentivized, Luftseben members chartered the Waterskiing club, the Ski Club, the Geology Club, and others, and the Quigley Club followed suit, ultimately resulting in Cunningham’s downfall.

The Vietnam War comes to Western

Before his sacking, one of Cunningham’s editorial pushes at Top O’ the World was to assemble two full pages of letters and editorials about the ongoing Vietnam War.

“I wanted to have as many letters as possible, I announced that. Of course, the antiwar people were much noisier than the pro-war people. I had quite a few antiwar articles … and a poem about the war, and it appeared that I was not very objective about it,” says Cunningham of the editorial disparity.

Although his firing came shortly after that piece ran — and it was cited by some detractors as the rationale for his dismissal — he views the timing as more of a convenient excuse to pounce on him by the Quigley Club members than a genuine journalistic stance.

Cunningham remembers that Prof. Trần Văn Dĩnh, a Vietnam native and scholar who had held posts in Vietnam’s diplomatic corps in Asia and in America, came to Gunnison to speak in opposition to the ongoing war. Sadly, the professor and peace activist was greeted with anti-Asian discrimination while at a local gas station.

Despite the outburst of editorials in Top o’ the World, Cunningham says that antiwar sentiment at Western was rather muted compared to many other American universities for a variety of demographic and geographic reasons.

“We always joked that there had been an antiwar protest at every college in the state of Colorado except Western State,” he says.

In fact, Cunningham recalls that some students affiliated with the Quigley Club organized a series of “study-ins” to lobby in support of the war.

“It was to support the war, and to support scholarship, and to support good citizenship, and so they would have these study-ins all night long and cloak it in patriotic themes. I didn’t go to any,” relays Cunningham, who believes that Gunnison’s physical separation from the world played a key role in suppressing antiwar sentiments.

John remembers having little to no access to television (a cable system was being installed during his days at Western, but was not popular at the time). The Denver and local radio stations would both finish broadcasting by 5 p.m.

That left KOMA Radio in Oklahoma City as Gunnison’s lone consistent connection to the outside world during the evenings.

The news that Gunnison did get via radio was rather conservative, mirroring the views of the region’s population, largely farmers and ranchers who lived off the land.

Cunningham vividly remembers watching a cattle drive come down above Kelley Hall while sitting in class one day.

“There aren’t a whole lot of colleges where you would watch a cattle drive come down through the edge of the campus,” he says with a chuckle.

Gunnison’s place in the world

After Cunningham was fired in the spring of 1968, his successor at the newspaper was arrested (and later convicted) for breaking and entering into the Western Motel.

Cunningham ended up writing about the incident on his new beat with the Gunnison County Globe, the town newspaper and the precursor to the Gunnison Country Times, which ceased publication in 1975.

“Revenge is sweet,” says Cunningham with a laugh.

His beat with the Globe varied widely, from covering Crested Butte school board meetings to passing judgment on such important matters as the paper’s featured “yard of the week”.

John also pitched and wrote stories that suited his historical inclinations, like a feature on the Pioneer Cemetery located near Dos Rios.

He remembers being bewildered when asked to cover the town’s longstanding summer rodeo, Cattlemen’s Days, which began in 1900.

“Being from Denver, [and] being a city kid, I had no clue about anything [rodeo-related],” he says. “Like ‘what the hell is this stuff?'”

The outside world comes to Gunnison

But news and broader culture occasionally did occasionally make their way into Gunnison. Gus Grissom was a former U.S. Air Force pilot and an astronaut in the Project Gemini and Apollo programs, and he became the second American to fly into space in 1961. Grissom made a trip to Gunnison during Cunningham’s tenure at the Globe.

Cunningham covered Grissom’s arrival, and remembers Gunnison’s mayor at the time remarking, “’My God, this is really gonna put us on the map!'”

Even reaching Gunnison was much harder in those days, says Cunningham, who notes that the planes that made the trip from the Front Range were referred to as “vomit comets”.

Overall, Cunningham looks back fondly on his Western days, and appreciates the experience he picked up writing for both Top o’ the World and the Gunnison County Globe.

His passion for writing has continued long after his Western days, and he maintained his own website entitled “The Lost City of Colorado Springs” where he wrote historical features, including on Colorado Springs’ local minor league baseball team, the Sky Sox, which has since been relocated to Amarillo, Texas.

Cunningham’s website functioned as a sort of personal campaign to document the culture and history of Colorado Springs.

“I felt like Colorado Springs has been growing so fast that we’ve lost where we’ve come from … I don’t think there’s much heart to the city right now, and it’s nobody’s fault,” explains Cunningham.

After departing Gunnison, Cunningham taught history and economics in his hometown Colorado Springs for three decades before his retirement.