For art students, becoming a Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) student is an honor, achieved by submitting three top works, in addition to the artist’s transcript, an art history paper, and a formal artist statement for faculty review.

BFA exhibitions are often large in scale, spanning significant wall space within the Quigley Gallery. As part of his BFA exhibition, senior art student Daniel Lesh created 12 works, each one paying tribute to a different instructor, mentor, or Western art professor.

“My show is about celebrating each individual lesson I’ve learned from each individual teacher I’ve had,” says Lesh. “My work seeks to critically observe, symbolize, and celebrate those who shape our perceptions of the world and who we become,” Lesh adds in his artist statement.

An artist’s beginning

Lesh first first delved into art in middle school, pushed by his school’s requirements to take either art, music, or physical education. At the time, Lesh was not taking art all that seriously. “It wasn’t until 10th grade that I really did start taking art seriously,” he adds.

“I made this realistic drawing of Emma Watson, in the summer–I never finished it. Looking back, I’m like ‘Yeah, it’s an okay portrait.’ [But] in the moment, back then, that was a huge game-changer. I was really excited,” says Lesh, who was inspired by his love for Harry Potter.

‘It very slowly unfolded, this love for art,” adds Lesh. For his senior project in high school, Lesh explored different mediums – like ink drawing and painting – outside of his comfort zone, which at the time was realistic pencil drawings. By the time Lesh made the decision to come to Western, his passion for art was aflame.

Crafting an exhibition

Flash forward to this spring, and Lesh’s BFA exhibition allowed him the opportunity to dabble in different mediums. While many of the pieces are oil paintings, Lesh also got to flex and expand his graphic design, ceramics, and drawing skills. Lesh was intentional about choosing the frames used for each piece, picking frames that bolstered the feel and aesthetic of each work.

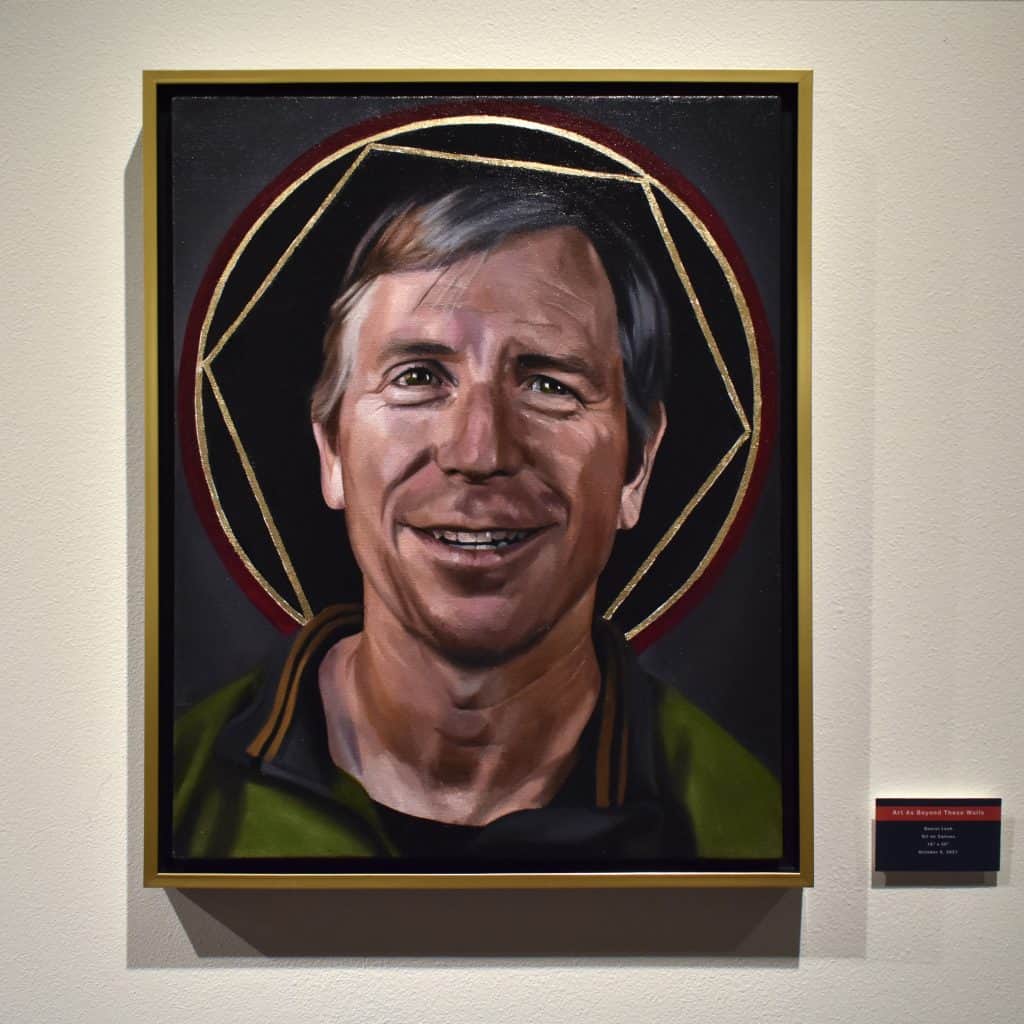

For example, Professors Jason Mullins and Jen Herdman, who both teach in the Chemistry Department, are showcased with gold-leafed, geometric symbols behind them, paired with thin, gold frames. The gold leaf, due to its delicate nature, posed a material problem of its own. “When I try to put gold leaf on a finished oil painting, it becomes really difficult. Not all art materials mix well together,” adds Lesh.

Professor Herdman taught Lesh for Chemistry 100, a course that emphasized material science. Professor Mullins taught that course’s sequel, Chemistry 101, and imparted knowledge of stoichiometry and chemical equations. The knowledge transmitted by Herdmen and Mullins in the chemical arts is reflected in the respective pieces “Art as Material ” and “Art as Beyond These Walls.”

The latter title reflects Lesh’s belief in interdisciplinary education as a building block for success. “I strongly believe that artists should take other disciplines, such as science, literature, math, business, [and others] seriously because all forms of study influence the way we perceive the world,” says Lesh.

The triangular shape behind Professor Herdman represents strength, and the hexagon behind Professor Mullens represents a benzene ring, a fixture of organic chemistry. The symbols serve to fuse together the artistic and the scientific.

Lesh’s portrait of Professor Emily Loehle, entitled “Art as Discipline”, reflects the drawing skills Professor Loehle passed to Lesh early in his Western career. “You can see that in the bottom left corner is a black and white scale. What I wanted to do was represent how artists break down the visual world,” Lesh offers.

“That starts with seeing things in terms of lightness and darkness, that’s the scale. Then we apply lightness and darkness to a form, that’s the sphere. Then the three circles above are studying that form…then we try to apply value to something more complex, like a skull,” relays Lesh on the sequential building blocks of drawing.

The first piece Lesh began working on was the portrait of Rick Thompson, a custodial worker in Quigley Hall. The work, entitled “Art as Beginning”, was a reflection of the wisdom Thompson imparted.

“Something he really emphasized was how to not get too caught up in the work of life, that the purpose of life was greater than being a worker. This changed who I was as a person and who I was as an artist,” says Lesh. “He was my teacher, [although] he didn’t have the title of a teacher…teachers [can] come from anywhere.”

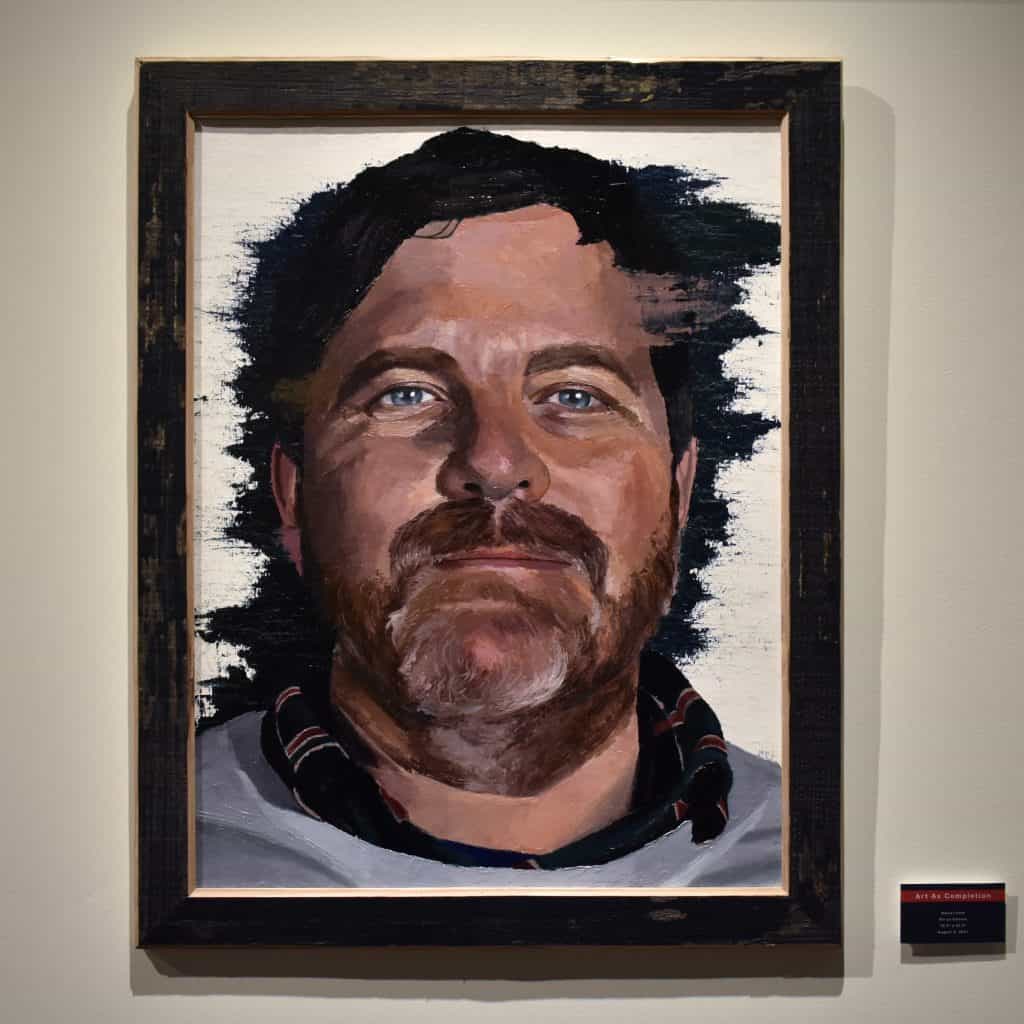

Other pieces reflect specific lessons picked up from different instructors, like Lesh’s portrait of Anders Johnson, titled “Art as Completion,” which was solely painted with a palette knife. “For people who don’t know, that’s a tool for mixing paints, not usually for applying. But it’s great for applying thick layers of paint in this very loose, painterly way,” notes Lesh.

“The only area that’s not painted with a palette knife are the eyes. The point of it is to draw you into his eyes.” Lesh derived the piece’s name from the unfinished canvas, which harkens back to a discussion he had with Professor Johnson that investigated the nature of completed work.

“When do we decide that it’s done? Is it when every pore is drawn? Is it when every hair is painted? What dictates when we finish pieces?” inquires Lesh. “His face is done…but there’s this raw canvas around it, so is it [really] done?” The frame for the piece, weathered wood, plays with the piece’s theme of unfinishedness.

Lesh’s portrait of Professor Chase Hutchison, the Chair of the Art Department, reflects Professor Hutchison’s own vast skills in drawing, most often single-line drawings. For the work, entitled “Art as Interdisciplinary,” Lesh drew Hutchison photo realistically as an homage to the photography course Lesh took with the professor.

“I did these faces of single-line drawings of my own, and I collaged watercolor washes into different shapes to represent eyes. It kind of looks like stained glass. They’re kinda organized like a comic panel because he’s a huge comic nerd,” says Lesh of his homage.

Moving through the exhibit, Professor Heather Orr’s piece was actually Lesh’s first in the series and draws inspiration from standard Renaissance portraits. “She’s this really well composed woman, cut off at the bust length. There’s drapery behind her, and she’s leaning on it– and there’s this really heavy focus on the drapery. I hit the light right on her forehead, so it highlights her intelligence, that’s something Rembrandt did,” says Lesh of the art history references he wove into Professor Orr’s piece.

She imparted the foundational knowledge of art history onto Lesh, thus inspiring “Art as Knowledge.” Lesh adds that the whole piece is done in a glazing technique, invented by Jan van Eyck, the founder of oil painting.

For the piece of Professor Mayela Cardenas, Western’s graphic design professor, Lesh stepped outside his comfort zone with a medium he is not as experienced with. “It only uses linear shapes, there’s no curved lines anywhere, to build this abstract, very creative, very color theory-based portrait,” says Lesh of “Art as Precision”.

When Lesh is painting, he can mix colors as he goes, creating thousands of color iterations on the fly. With graphic design, he’s more limited in his color options he uses in Adobe Illustrator, deploying just about 10 colors strategically to bring the piece to life.

Professor Jeff Erwin, the newest of Western’s art professors, delves into more experimental artistic styles, reflected in Lesh’s portrait of the professor “Art as Experimental”.

“I had to draw, and paint, and then paint ‘em again, so there are three pieces I did. And then I had to cut them up and collage them together, not really knowing if they were gonna line up, [or] if they were gonna look good,” adds Lesh, who says the piece is largely about trusting the artistic process, especially as a more technical artist making a foray into the experimental realm.

At the end of the gallery line, Professor Tina Butterfield’s piece, entitled “Art as Precious”, was meant to draw the viewer’s eye. “[With] this great big bright red painting, you’re going to want to come all the way down to the show to see it. It’s a realistic portrait…I covered half the painting with red paint, including the frame, because her main lesson was that artists need to detach themselves from their work in order to learn. It’s the idea of a growth mindset,” says Lesh.

Finally, off to the side in Lesh’s gallery display, was Lesh’s Professor Al Caniff piece, “Art as Central.” Professor Caniff has been at Western for more than 30 years. “His is the smallest piece, but it is also [perhaps] the most important, it incorporates elements from every single of these pieces before. He has the unfinished quality of Anders’ piece, he has the black and white realism of Emily’s, he has this broken, unprecious quality like Tina’s, and he’s the ceramics professor,” expands Lesh. “He’s this really central, structural element in the department,” says Lesh, rounding out his dozenth piece.

Making Lesh’s work all the more impressive is the fact that he is balancing multiple roles on campus; as a student of course, but also as an employee working for Sodexo in the Rare Air Cafe (RAC) and for Quigley Hall as a custodian, as the head of the Student Art League, and of course, as an artist taking every free moment he can to steal away and work on his art.

That process of squeezing art into a busy schedule goes against Lesh’s natural inclination, which is to sit for hours straight and bang out his work in one long, uninterrupted session. “It’s convincing myself that it doesn’t matter how much time it is: 10 minutes? Get down and work,” says Lesh. Clearly, that attitude worked, with Lesh producing a dozen works representing hundreds of cumulative hours in the studio.

Eyeing post-graduation plans, Lesh wants to convert his passion for education and scholarship into a teaching role of his own, striving to become an art professor. Lesh has taken great joy in assisting his peers with their work and their shows, including recent BA graduate Sarah Ackerman.

In the world of art academia, a Master’s of Fine Arts (MFA) is the terminal degree, and most programs do not accept recently-graduated bachelor’s students, preferring work experience. After he graduates, Lesh will head to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to take a gap year while pursuing admission into the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s MFA program.

Editor’s note: Stay tuned for more features of Western student artists this spring.