Second year MS Ecology student Heather Reynolds studies the connections between restoration efforts and habitat usage

This story is part of an ongoing series highlighting Clark Family School of Environment and Sustainability (ENVS) projects and their relations to the broader environmental movement and to the Gunnison Valley community.

Gunnison Sage Grouse (GUSG) conservation has been a significant topic tracing back to the turn of the 21st Century, when the species was discovered and formally recognized. The species discovery was largely the result of the scientific research of Dr. Jessica Young, a Western ENVS Professor. Since that time, the GUSG population has declined to its threatened current status, and its total population is estimated at under 2,000 individuals. More than 80 percent of the species population resides within the Gunnison Basin.

While the species is currently listed as Threatened federally, a Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) lawsuit launched in 2020 seeks to tighten restrictions on livestock grazing and other forms of species “taking” to try to stem population losses. An excerpt from a December 2020 “Wildlife Society” article:

“The groups say Gunnison sage-grouse, which are found in southwest Colorado and southeast Utah, are facing “catastrophic population losses,” citing a 40% drop in the Colorado population and a 50% decrease overall since 2013. In 2014, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Gunnison sage-grouse as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Gunnison sage-grouse conservation is based on the Gunnison Basin Candidate Conservation Agreement and the underlying biological opinion developed in 2013 to guide conservation measures. Parties to the agreement are permitted to cause some incidental take from certain development, grazing or other covered activities in the bird’s habitat.”

Local conservation efforts have attempted to aid the grouse’s survival by bringing ranchers, trail users, public lands officials, and city and county government personnel to the table to assist in species conservation planning and monitoring.

Despite these valiant efforts, threats from invasive plant species, a warming climate and a drying basin, and encroaching development, combined with conflicted interests in building increased housing, expanding trail systems, and continuing historic ranching operations have contributed to the GUSG’s steady, ongoing decline since the species was first discovered.

Encouraged and mentored by Dr. Jessica Young herself, second year Master’s of Science (MS) in Ecology student Heather Reynolds set out to analyze the effectiveness of habitat restoration measures, and the populations of GUSG, across the Gunnison Basin. “She’s been my number one supporter, she’s just absolutely incredible in terms of an advisor,” says Reynolds of Dr. Young.

Reynolds came to Western aiming to focus her efforts on human-wildlife conflict, and with the case of the GUSG, she found a readymade project where she could immediately plug in. Dr. Young encouraged Reynolds to build off a project started in 2016 by Colorado Parks and Wildlife Biologist Nate Seward, which uses trail cameras to examine populations of grouse in wet meadows.

Reynolds took over the data analysis and management of the camera project, which includes data for 36 different wet meadow areas spanning the Gunnison Basin. Half of these sites have been “treated” with restoration efforts such as one rock dams, and half of which are untreated.

Reynolds maintains the cameras, changing the batteries, performing vegetation maintenance, swapping out the SD cards, and examining and tagging the photos. “The project right now has over three million photos, and for perspective, about 6,500 of [those are] grouse…the majority of [the photos are] cattle,” says Reynolds. Reynolds will pick out and label the grouse, taking counts from each photo.

Analyzing restoration success on the ground is a complicated endeavor that raises a number of complex factors. The easiest factor to measure is vegetation change. GUSG are heavily dependent on wet meadow ecosystems to find forage, the insects and forbs (herbaceous, non-grass plants) necessary to survive from the time they hatch in the late spring and early summer to their first fall when they become self-sufficient.

Reynolds’ primary time block of study spans from mid-June to mid-October, the critical 18-week period where juveniles are most abundant on the wet meadows. Most of the grouse Reynolds sees on the cameras are juveniles, owing to the need for juveniles to forage on the wet meadow sites in their first half-year of life. “We do see plenty of adults, because the adults are opportunistic feeders,” adds Reynolds.

The ultimate goal of Reynolds’ study is to inform best management practices on the ground. “One way we can try and support the grouse is by supporting their brood-rearing season. Their population is limited by getting chicks and juveniles into the breeding population. And adult sage grouse, they can eat sagebrush year-round, they’re fairly hardy,” says Reynolds.

But when wet meadows become degraded by human activities and erosional forces, sagebrush creeps into the dry meadows. “Sagebrush doesn’t like to have its feet wet, it starts to die after 36 hours of having wet roots,” says Reynolds, adding, “Wet meadows have historically become degraded due to human presence on the landscape which primarily has changed the hydrology of these systems. When this happens, sagebrush creeps in and you no longer have the productive wet meadow that should be dominated by wetland vegetation.”

The first measure of success, then, is converting historic wet meadows from sagebrush back to wet meadows. So, one of the key factors Reynolds examines is a drought index. “In restoring these sites, you are hopefully increasing drought resiliency,” says Reynolds. She notes that when the study sites were first demarcated, many of the sites were selected because they were known to attract an abundance of grouse, influencing the data.

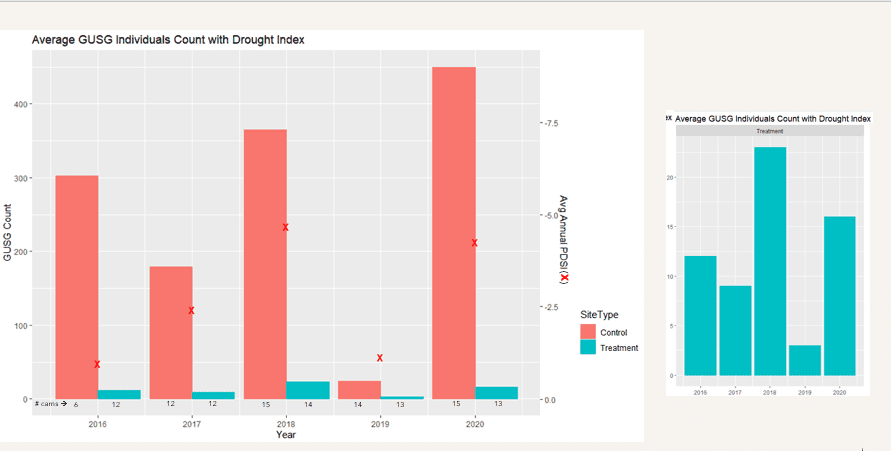

What Reynolds has not seen in her dataset may be the most illuminating finding of her study: grouse are not moving from the untreated sites to the restored sites as might have been expected. Just eight percent of the grouse photos have been captured on treated sites (with the majority on just three of the 36 sites), yet the annual patterns in grouse photo count between the untreated and treated sites track almost identically.

“There can be two sorts of explanations for that. The main one is [that] they have really high site fidelity… we might need to do this for another ten years before we start to see grouse moving into these [restored] sites more. Another thing we could maybe focus on is trying to restore sites where we know they go,” says Reynolds, who quickly cites the dangers of disrupting sites as a possible counterpoint, before continuing on.

“The restoration is justified, [however], because it’s not just grouse that are benefitting, other bird species, we have a ton of elk, mule deer, I’ve seen a ton of different rodents, rabbits and little weasels, bears, mountain lions, bobcats, moose…tons of different wildlife species are using these areas. And of course, cattle. It improves grazing for cattle,” says Reynolds. The benefits for cattle have played a major role in aligning the interests of ranchers and biologists for this specific project. Everyone wants to see the wet meadows restored to the landscape.

Despite the fact that grouse are not switching sites readily over the study’s first five years, Reynolds keys in on the positive changes in vegetation as a hopeful sign that demonstrates habitat restoration has the intended impacts: increasing moisture and revitalizing wet meadows.

But then there are more seemingly puzzling findings. 2018 and 2020 were both bad drought years, yet GUSG study counts were up in both years, and down in 2019, a relatively wet year. Reynolds believes this is likely the result of GUSG relying on wet meadow areas even more heavily during the drier years (as opposed to drier, upland sites), leading to more photos across all sites. In 2019, GUSG may have opted to stay in the upland with the wetter conditions, which provides more cover from predators than the more open wet meadows.

Reynolds is still deep in the process of analyzing her data currently, making her first foray into the RStudio statistics analysis software, with the aid of recently hired Wildlife Ecology Professor Madelyn van de Kerk, who specializes in quantitative methods related to wildlife biology. Reynolds plans to defend her thesis in the summer when the analysis has been concluded.

The biggest challenge during the project? Besides the data-crunching, Reynolds cites being a newcomer to the world of the Gunnison Sage Grouse. “Being the new person on an established, well-known [wildlife] project has been a curveball…the truth is there is no way I could possibly learn about every facet of this project,” she adds. “The good thing is [that] everyone has been willing to get me up to speed.”

Reynolds will be at the Gunnison Sage Grouse Summit on April 4 and 5, amongst a slew of other presenters discussing the grouse’s population trends, related wildlife and restoration efforts, and updates on ranching, trails, vegetation, and a host of other topics related to the bird’s survival.

Reynolds came to graduate school to acquire the knowledge and tools required to be useful in the wildlife management world. “The whole thing is rewarding, as difficult as it is, as much as I want to be done right now. Overall, the product is really, really rewarding,” says Reynolds of the Gunnison Sage Grouse, a species she didn’t know before she came to Gunnison, but quickly grew fond of.

“One thing I also love about this project is that yes, when they’re leking they’re really fabulous, but otherwise they’re just a little brown bird that’s sleuthing around the sagebrush. I’m so glad that they caught someone’s attention a couple decades ago, and we started figuring out their story…let’s give ‘em a chance, let’s keep fighting for ‘em.”

Editor’s note: Don’t miss out on the fifth GUSG Summit on April 4 and 5. Zoom registration is still available for latecomers.