By Kira Cordova

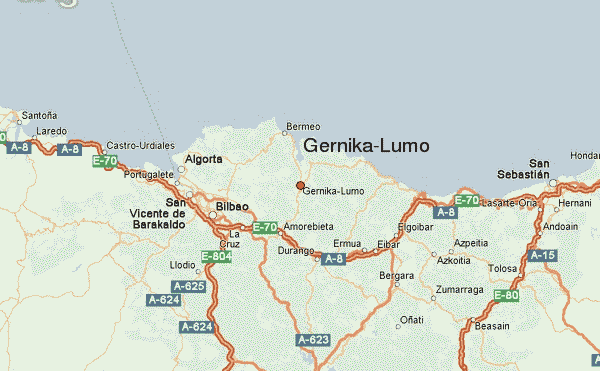

Note: The author is currently studying abroad in Bilbao, Spain, an hour’s drive from Gernika, a small town in the province of Biscay, Spain. They virtually interviewed the Founder of the Colorado Peace Heroes Museum in Gunnison, Lishka Blodgett, before the museum opened on May 6th.

In keeping with the spirit of collaboration between international peace museums, she reached out to the Gernika Peace Museum and had the privilege of interviewing the Founder and Director, Iratxe Momoitio Astorkia. The interview was in Spanish, and the original quotations in Spanish are included. The author’s translations are in italics.

“Se ve que Gernika es un trabajo no solamente que quería tanto una ciudad mártir que llora sus víctimas solo y llora sus tristezas, sino que quería dar un mensaje a favor de la paz también y los derechos humanos, que no haya más Gernikas,” says Momoitio.

“Gernika is a project that didn’t want [to be] only a martyr city that cries for its victims and their sorrows, but one that sends a message in favor of peace and human rights too, so that there are no more Gernikas.”

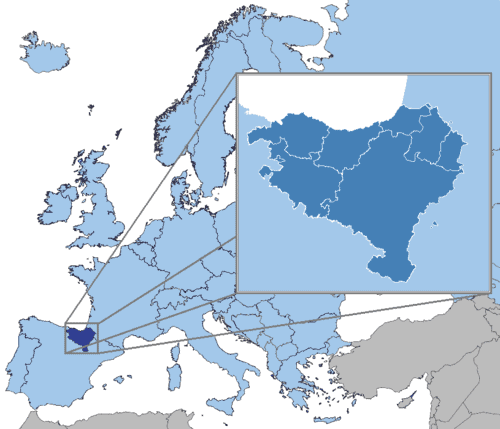

Gernika is the historical capital of what is now the province of Biscay in the Spanish Basque Country. The city assumed the seat of the junta general of Biscay (the traditional parliament, which still exists in a more modern form today) more than five hundred years ago, in which community leaders met to debate and democratically decide on local issues.

This Basque tradition inspired John Adams to make a research trip to Bilbao, the modern capital of Biscay, in 1780, shortly after the founding of the United States as a republic. Although the United States eventually didn’t incorporate Basque systems into the current constitution (which was signed in 1787), Adams wrote about the Basque Country in his letter “A Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the USA” in 1878.

Gernika (spelled Guernica in Spanish) is infamous for a much darker event, though, one that involves the Spanish Civil War, which transpired from 1936 to 1939. The war divided the country along ideological and economic lines between the fascist, monarchical, and predominantly wealthy Nationalists, and the Republicans, those who supported the previous Second Spanish Republic, including anarchists and members of the Spanish Communist Party.

On April 26th, 1937, during Spain’s civil war, Nazi Germany (an ally of the fascist Nationalists, led by the future dictator of Spain, Francisco Franco) bombed the city on a market day, targeting civilians and destroying more than 90 percent of the town.

The Nationalists followed the bombings with a series of misinformation, broadcasting that the Republicans had destroyed Gernika by setting the city on fire. The destruction inspired Picasso’s famous painting “Guernica” after the artist read about the bombing in an article by George Steer, a British foreign correspondent for The Times who fought against the propaganda, photographing the aftermath and interviewing survivors.

In the present day, the Gernika Peace Museum aims to honor the survivors of the bombing, tell their collective stories, and promote peace, human rights, and historical memory.

In addition to a permanent exhibit about the bombing, the museum rotates a number of collaborative exhibits and educational programs inside and outside of the museum’s walls, like family museum days, guided tours, and even gastronomic activities.

It also houses an archive of more than 7,000 books and extensive documentation from around the world about the war, bombing, and repression during the almost 40 subsequent years of dictatorship in Spain.

Back in 1996, Iratxe Momoitio had just finished a dual degree in Basque Language, Philosophy, and Letters (Filología vasca y Filosofía y letras) at Deusto University, and was working as an au pair in France cementing her french language skills, when a scholarship from the ayuntamiento (local government) of Gernika opened.

They were looking for someone to research and compile all available historical documentation about the bombing of Gernika and the Spanish Civil war in the international archives.

Momoitio accepted the scholarship from the local government and took on the colossal project of compiling all of the international documentation about the bombing and the war. At the time, there was no permanent exhibit concerning the bombing of Gernika.

The local historical group, Gernikazarra historia taldea, had already researched and compiled information from archives around Spain, which they incorporated into a seasonal exhibit about the bombing in the summers. However, Momoitio says it was difficult for visitors to Gernika to find information about the town’s history and the tragic event.

When Momoitio started investigating internationally, she says it quickly became clear that further research in Spanish archives was necessary, and she spent the entirety of 1996 diving deep into the existing documentation across the country.

She extended her scholarship into 1997, branching into archives in England, France, and Italy. In 1998, the information she had researched and compiled led to the foundation of what was originally named the Gernika Museum, which also incorporated the prior work of Gernikazarra and the Center for Research for Peace Gernika Gogoratuz, which focuses on conflict resolution and oral history, and was instrumental in the process of reconciliation with Germany.

This new museum, in addition to the archives of compiled documentation, housed a small exhibit on the bombing of Gernika, which has since evolved into a new permanent exhibit after the museum was remodeled.

Momoitio says a transition towards peace education and the museum’s current model started in 2001 with the reconciliation process and a grant to remodel the space. What was then the Gernika Museum has now belonged to the International Network of Museums for Peace, a network of more than one hundred museums worldwide (Momoitio is currently the co-coordinator), for more than twenty years.

When the museum reopened in 2003, though, the new space brought new possibilities to house peace education and exhibits beyond the bombing. This focus crystallized with the museum’s new name: the Gernika Peace Museum.

“En el mismo nombre se reflejaban las dos cosas, tanto la parte histórica como la parte de paz,” Momoitio says. “The new name reflected both things, history as much as peace.“

A team from Gernika traveled to visit various international peace museums as part of the remodeling and renaming process, just one example of the museum’s history of collaboration with other museums and organizations, both locally and globally.

“Siempre hemos tenido claro que no somos los únicos,” Momoitio adds. “We’ve always had it clear that we’re not the only [Peace Museum].”

And the museum’s list of collaborators doesn’t end with other peace museums. The team has also collaborated with artists, universities, activists, and other individuals and organizations, including the Reina Sofía Museum and the University of the Basque Country (Universidad del País Vasco, or UPV).

The museum also cooperated with the Chilean art collective Casagrande to bring a “Bombardeo de Poemas” (poetry bombing) to Gernika in 2004; dropping leaflet “bombs” of poetry from helicopters to pay homage to the victims of historical bombings, and to bring awareness for peace efforts.

In 2017, the museum collaborated with Agroarte Columbia, an organization that fosters both memory and resistance via symbolic events. Members “planted” themselves and resprouted from the plaza outside the Gernika Peace Museum in an act of resistance against violence.

“Siempre se aprende de otros,” Momoitio offers. “You always learn from others.”

She adds that collaborations like these often lead to joint publications and to “buenas amistades que luego hacen que surjan nuevos proyectos,” or, “good friendships that later make new projects arise.”

For instance, Momoitio said that a recent collaborative exhibit with art students from the UPV about historical memory, the Spanish Civil War, and dictatorship will hopefully be developed into an annual cooperative art exhibition with local artists every spring.

She emphasized that exhibits and events like these are vital because of their ability to forge new connections, and to reach people who wouldn’t otherwise visit the museum.

The museum offers extensive educational programs, which purposefully take varying forms. For Momoitio, “la educación tiene mucha potencia si somos capaces también de hacerlo de maneras diferentes.”

“Education has a lot of potential if we’re also capable of teaching in different ways,” she says, adding “Tenemos que ser un socializador de la memoria, de la paz, y de los derechos humanos”

“We have to be a social influence for memory, peace, and human rights.”

Through its youth education, the museum aims to incorporate the history of the bombing and the civil war into stories about more recent conflicts and peace efforts. Momoitio stressed that, while the bombing of Gernika 85 years ago might seem ancient to younger students, the fundamental issues remain the same.

“Los jóvenes y los niños saben del presente, entonces hay que hablar de esto, los otros Gernikas, los otros sitios que por desgracia no aprendemos mucho y seguimos repitiendo.”

“Young people and kids know about the present, so you have to talk about the other Gernikas, the other sites that, unfortunately, we don’t learn much about [so we] keep repeating them,” she says.

Education at Peace Museum Gernika does not stop at school programs, though. “Intentamos también trabajar por un público variado,” she says. “We also try to work for a varied public.”

The museum wants to offer not only education for children, or research opportunities for scholars and academics, but a broade appeal to “un amplio abanico que gente que podría visitar el museo,” or “a wide range of people who could visit the museum,” Momoitio says.

To that end, the museum started offering online seminars during the pandemic. For Momoitio, art, including theater, music, and poetry, is a vital part of peace education.

“El arte es otra manera de transmitir que muchas veces no con palabras, a veces [con palabras] también, y llega muy dentro de la gente,” she elaborates.

“Art is another method of transmission, often without words, and sometimes with them, and it reaches deep within people.”

She emphasized that art is also a way of reaching past the doors of the museum. Art’s ability to appeal to human emotions, and its capability to permeate spaces outside of the museum, make it a powerful way to reach people who would otherwise never walk in.

“Yo soy consciente de que a no todo el mundo le gustan los museos y que no todo el mundo ha visitado nuestro museo,” Momoitio offers. “I am aware that not everyone likes museums, and that not everyone has visited our museum.”

But Momoitio does not want the museum’s format to be a barrier to entry. “Al final, no nos importa tanto la herramienta que utilicemos para transmitirlo, sino la transmisión,” she elaborates.

“In the end, we don’t care as much about the tool we use to transmit [the message] as we care about transmitting it.”

Then, Momoitio pivots towards her vision for the museum:

“La cosa es difundir un poco todo lo que ha pasado en diferentes lugares del mundo […] o las personas que han sido más desconocidas, que históricamente necesitan también que se les rescate, que se les homenaje en algún lugar por el labor que en su día hicieron.”

“The idea is to educate a little bit about everything that’s happened in different places around the world…[and about] the people that have been more unknown, who historically need to be rescued, to be honored somewhere for the work that they did in their day.”

Working to recover those very stories and link them to modern day issues, the museum has plans to collaborate with Sites of Conscience, a global network of historic sites and museums, and has developed an exhibit on humanitarian crises for the Gernika museum next fall in cooperation with international collaborators, including the Museum of Terezin and the Musée de la Mémoire in France.

Ultimately, the museum’s goal is to maintain and improve the varied exhibits and events the museum already offers. When it comes to historical and peace education, “una cosa es leerlo y otra es vivirlo,” Momoitio says.

“It’s one thing to read about it and another to live it.“

As impressive as it is informative! Kudos to this student for fully embracing study abroad.