“You just got to be adaptable. As the world’s changing and you want to keep these traditions alive you got to figure out ways to keep them alive, and you might have to say goodbye to a few things, and that’s okay,” says Justin Gallen, the owner of the Gunnison-based boat shop Raindog Boatworks.

Gallen grew up in a small town in northeastern Oregon. The son of a raft guide, he became a guide himself, and boasts more than a decade of experience navigating the rivers of the southwest, including the Grand Canyon, the San Juan, and the Salt in Arizona.

Gallen also worked for Grand Canyon Youth (GCY), an educational and service-based expedition organization, as a Trip Leader. In his teenage years, Gallen recalls being party to a GCY outing that fueled his love for rivers and boating.

An education in boating

Later in life, Gallen remembers looking on in awe at wooden dories during his tenure as a river guide in the Grand Canyon. Then in 2015, Gallen received an invitation to check out Brad Dimock’s boat shop, Fretwater Boatworks, where wooden dories were constructed.

“I walked in and saw the boats they were working on, and just didn’t leave for about an hour. Brad handed me a Japanese pole saw and told me to get to work, write down my hours at the end of the day, and come back to work the next morning. That was my job interview,” Gallen says.

That meeting was the start of Gallen’s five-year apprenticeship with Fretwater and Dimock, which included the creation of the Doryak. “He’s a historian, an author, and he’s done a lot of work just to keep these boats alive,” Gallen remarks of Dimock.

Gallen notes that Dimock and Andy Hutchison of High Desert Dories are the preeminent wooden boat builders in the southwest. Both have roots with Martin Litton, the owner of Grand Canyon Dories, a company he founded in 1971, and later sold to OARS—a leading adventure travel company, in 1988.

Litton was a renowned river runner and conservationist, credited with saving the Grand Canyon from prospective damming, and with popularizing wooden dories—previously used in Oregon—both in the southwest and more broadly.

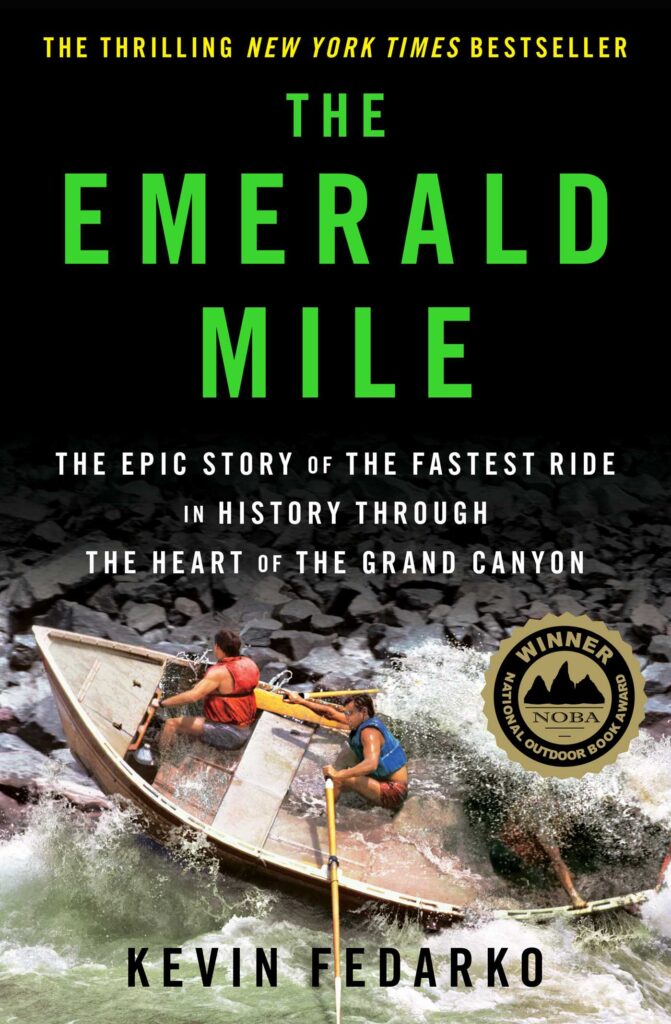

Also boosting the renown of wooden dories was the 2013 book “The Emerald Mile”, which recounted a river trip down the Grand Canyon in 1983 during exceptionally high flows. The book derives its name from the eponymous wooden dory—slated for destruction before being revived and restored—that carried the three boaters down the 277-mile stretch of river in less than 37 hours, a record which would stand for more than three decades.

“The [book] piqued a lot of people’s interest in dories,” says Gallen. The book, in fact, spurred a bump in boat purchases of all varieties.

When Gallen worked for Fretwater, he built a fleet of wooden dories for Canyon Explorations, a company he had previously guided for. That purchase marked the first commission of wooden boats for a Grand Canyon company since 1981.

Going into business

After years of guiding, education, and boat building, the pandemic hit, and Gallen moved to Gunnison to be closer to his brother and parents, officially launching his own boat building venture, Raindog Boatworks, at the end of 2020.

Raindog primarily builds two models of wooden dories, the one-person “Doryak”, a nine-foot boat designed by Fretwater Boatworks—with Gallen’s help, down in Flagstaff, Arizona, and a vessel of his own design, the “Gunnimoon”, a 10.5’ boat which seats two.

Gallen finished up the first-ever Gunnimoon just in time to take it, and the Doryak, out on a twenty-day Grand Canyon expedition in April, testing the boat’s mettle on a stretch of river with a storied history of wooden crafts.

“It was its first time touching the story, it’s kind of a hesty test,” says Gallen with a grin. “But it passed, it did really well, and I am really pleased with it.”

Nowadays, most boats built for river usage rivers are made from fiberglass or aluminum, in addition to the typical rubber rafting boats. Designed as fishing boats initially, Gallen notes that wooden dories can be constructed to withstand serious whitewater—hence the added decking on the Doryak and Gunnimoon models.

With smaller models, like the ones Gallen builds, that boaters are afforded additional maneuverability, and the ability to hit lower, more technical water. He has also brought the dories to the Lochsa River in northern Idaho, which has more than 40 major rapids. The boats held their own.

In the construction of the boats, choosing the proper wood for the job is critical. White oak, Gallen says, is a cornerstone of boatbuilding, often found in eastern sailboats. “It’s your standard, really strong marine-grade wood to work with,” he says. White oak can be found here in town at Western Lumber.

Other woods are more difficult to source, but worth the effort for their distinct properties. Gallen makes special trips to acquire Port Orford cedar, which only grows in southern Oregon.

The cedar is used in the boat’s structural components—the ribs and deck framing. “It’s rot resistant, super lightweight. Clear grain—really easy to work with, and really strong for its weight,” adds Gallen.

Marine-grade, rot-resistant plywood, Gallen says, is the trickiest to find. Meranti plywood is the wood of choice, a product of the red mahogany tree, a false mahogany species that is imported from Indonesia and the Philippines. The species, however, is endangered, and Gallen says he is considering the viability of switching to Douglas fir plywood, which some builders in Oregon use.

Raindog Boatworks also constructs paddles—made from Port Orford cedar—and oars, constructed out of eastern white ash, a flexible, strong, and shock absorbent wood. “When you row with ash oars, you can feel the flex,” Gallen adds.

The dory advantage

Gallen adds that while wooden boots can require significant maintenance and repair work—especially for boats put to the test in whitewater—they are far easier to restore than aluminum or fiberglass models. “You can clean [wood] boats up really well after a full wreck, they look brand new,” adds Gallen.

To demonstrate his point, he notes that of the 38 boats that Litton commissioned from Jerry Briggs, a master boat builder who built the original Grand Canyon dory, 37 are still in use today.

“Whereas a rubber raft, there’s a life span on a rubber raft. The rubber will just decay, and you can’t use it anymore,” notes Gallen.

On the environmental side, dories have some distinct advantages over rubber rafts, the production of which are intensive from both a chemical and carbon emissions standpoint. Rubber boats can also leach chemicals into the river. “The rubber industry is its own monster,” notes Gallen.

“That’s [another] reason why I like the idea of wooden boots. Sure, you might scrap over a rock, but it’s just going to leave [mainly] wood splinters—there’s plenty of wood in the river already,” he notes.

Gallen is increasingly trying to incorporate reclaimed wood, including Douglas fir, into his boat construction—both for its own sustainability merits, and for its utility as a cost cutting measure.

“With all the construction going on in this valley, there’s so much scrap wood [to go around]. [But] you still got to be choosy about the quality of wood you can use,” says Gallen, who is especially on the lookout for scrap Douglas fir.

“The good thing about wood, though, is that it’s an inherently renewable resource. If you plant a tree in the ground, it’s going to grow. [Then] it just depends on your consumption choice, and where you source it from.”

Presently, much of Raindog’s clientele hails from the river guiding community themselves. “They know the history of these boats,” notes Gallen. “They have the passion for it.”

In the future, Gallen wants to make inroads with the flyfishing community, and experiment with different building projects. He would like to build a lengthier two-person boat, and maybe even construct a wooden kayak—a unique creation.

“It would just be fun to build a wooden [kayak], but that’s definitely not going to be a [viable] market,” says Gallen with a chuckle.

You can learn more about Raindog Boatworks, examine their products and gallery, and grab their contact information on their website. They are also on Facebook and Instagram.