“There’s a lot of hot button issues that have to do with protecting the environment—Bears Ears, [different] pipelines, etc., and to really get involved with them, you need a seat at the table—and I’ve wanted that for a long time,” says Nicholas Story, a former Western Master’s in Environmental Management (MEM) student who has put his degree on hold while working abroad in Nigeria.

Before Nigeria and the MEM, Story had found work as a freelance consultant for a number of years after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Geography from the University of Colorado. His consulting work largely revolved around geographic information systems, or GIS, providing technical support to law firms, as well as contractors working on large-scale environmental projects.

From his home base in Colorado, the world of consulting has brought him in contact with environmental work in Colombia, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Australia, and Indonesia. During that time, he also found himself picking up seasonal jobs to fill the natural lulls in consultancy work, including a stint at a heliskiing company in Alaska.

In 2019, Story was looking to make a career move, and accepted a position as a Shoreline Cleanup Assessment Technique (SCAT) Team Leader for an oil spill cleanup and mangrove restoration project in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria—which boasts the third largest mangrove system on Earth. At the same time, Story enrolled in MEM, making use of the program’s online option and using the flexibility afforded to students to pursue his degree remotely.

He became involved with the Nigeria cleanup after completing some consulting work on behalf of a British legal firm that represented the community members of Bodo, Nigeria that were affected by Shell Petroleum Development Company’s oil spills.

The two major spills occurred in 2008 and 2009 after a 55-year-old pipeline ruptured twice, leaking large quantities of oil into the Niger Delta and its highly connected network of waterways.

In 2012, 15,000 members of the Bodo community filed a lawsuit in the London High Court—Shell is headquartered in the United Kingdom—citing damages to their health, livelihood, and land from the spills, particularly within members of the fishing industry.

Then, in 2015, Shell formally agreed to pay out more than £55 million pounds in damages and facilitate a cleanup operation to be overseen by the Bodo Mediation Initiative (the BMI, which Story is now part of), an organizational entity initially sponsored by the Dutch government.

As far as the litigation aspect is concerned “that’s long gone now, though aspects of it pop up from time to time,” Story adds. The BMI cleanup project officially commenced in the fall of 2017, though there were attempts to start the project earlier.

More recently, Shell was hit with a May 2021 Dutch court decision that legally mandates the company to make substantive progress (reducing emissions by 45 percent of 2019 levels by 2030) towards its 2050 climate goals, restructuring its business operations to comply with the ruling. Shell is currently appealing that court decision.

The cleanup operation

“I’m in charge of all field operations for the BMI,” says Story, who oversees a fluctuating team of roughly 30 representatives from various project stakeholders. His primary task is to ensure that the cleanup efforts comply with agreements forged between Shell, state and federal regulatory agencies, non-governmental agencies and the community of Bodo.

Currently, the project is operating in both phase two (which is now 73 percent complete), environmental remediation, and phase three, mangrove planting and monitoring. Phase one focused on addressing sequestered and free phase oil in a condensed time frame.

Story notes that a solid damage assessment was needed to specifically tailor the project to the expectations and needs of both the affected community and the regulators involved. He highlights the BMI project’s stringent monitoring program, and the continued flexibility demonstrated to accommodate the project’s diverse stakeholder groups.

“We go and inspect these areas as a team. It’s multi-stakeholder: We have the community, the oil company, and three different regulatory organizations… and we also have civil service organizations working with us out there as well. We also receive many other visitors interested in viewing the project’s success—such as UNEP [the United Nations Environmental Programme],” says Story.

From a communications perspective, everyone in the project team speaks English, although Story is proud to have picked up some of Bodo’s local language, Gokana. He says it can be helpful when interacting with local fishermen and community workers.

“Saying things like “good work” (“le tom”) or a simple “good morning” (oke-ya) to the community workers in their own language can have a positive impact,” he adds via email, noting the importance of learning local place names and landmarks for navigational purposes.

It’s all in the details

On the technical side of the project, Story and the remediation team have to contend with complex environmental factors in their day-to-day operations. Story notes that the sediment in the Niger Delta mangroves, where the oil is trapped, consists of peaty mud and sand. And because the team is working within an intertidal zone, the project areas are only fully exposed twice a day.

For cleanup operations, the remediation contractors use pump systems with meter-long nozzles inserted into the sediment column to flush oil out of the contaminated sediment. While they are there, they also remove tar, asphalt and trash, break up algal growth, and remove the invasive species nipa palm, which has been outcompeting mangrove recovery in disturbed areas.

Each remediation contractor has defined work areas that are subdivided further into a grid system. When the contractors finish work in a grid, Story and his SCAT team will come out to ensure the work meets the established criteria set by the stakeholders. This process is repeated for the more than 350 different grids, more than 2,000 acres of land in all. Thus far, Story’s team has completed over 2,000 site assessments.

Next, chemical samples from the grids are taken to ensure regulatory standards are being met. Finally, mangrove planting can commence—with its own set of standards. Monitoring teams will revisit the planting sites to ensure that the mangroves meet minimum survival thresholds—95 percent after one month, and then 70 percent six months in.

The technical aspects of the project can prove challenging on their own accord, but Story and the BMI also contend with shifting targets, shifting stakeholder demands and agendas, and logistical complications, which all can contribute to extending the Project timeline.

Currently, Story’s team is unable to work in the field because of a lack in military support, which may set them back another two weeks. Story adds: “I’ve definitely grown thicker skin. I’ve learned how to better deal with immense frustration.”

That learning curve comes with some growing pains. Story says he has witnessed contractors attempt to circumvent the integrity of the process and take the easy way out, including releasing flushed oil directly into the water where it can contaminate other areas, rather than collecting and properly disposing of it. These instances, combined with other, budding frustrations can lead to emotionally charged moments.

“There have been some situations here where I’ve totally lost my cool. I’ve had to reflect on that quite a bit because I’m generally a pretty calm and easygoing person,” says Story.

Lessons learned in Bodo

Yet Story notes that his experience in Nigeria has tested him on a mental and emotional level and ultimately made him into a better, more patient environmental manager. “A lot of it is just being present and understanding the situation well enough to make sound decisions”, he remarks.

This kind of international work can prove straining, especially as the months roll on. Story notes that feelings of isolation from friends and family have taken a mental toll, and are heightened by the stress of managing a large complex project under time pressure, and under public and media scrutiny.

But working on the Bodo project has instilled Story with both incredible patience and a habit for maximum efficiency when in the field. “Thinking about: If I have four teams out there, and I need to get [X] many sites done, and we can do each one in 10 minutes, but this team is a bit fatigued—[so] how many can I do in one day?” he asks. “Then it’s doing that four-five days a week,” he says.

When he gets time off, Story enjoys playing music and exercising, as well as traveling on the project breaks he receives every three months. Since he came aboard the Bodo project, he’s visited Mexico, Costa Rica, Greece, Italy, Switzerland, and France, in addition to trips back to the U.S.

“Being part of these big projects–it’s very rewarding despite the frustrations. I’ve been able to work alongside United Nations Environmental Program representatives who are now considering my advice for other projects,” Story relays.

Of course, the pandemic also presented a major hiccup in the midst of BMI’s efforts. After his initial arrival in Bodo, Story spent most of a year in Nigeria working uninterrupted on the massive, multiyear project.

But the pandemic had other plans, and he was forced to evacuate Nigeria in the spring of 2020.

“I got out here—we had to do a lot of legwork to get everything up and going. We were six or seven months into the project, and we were really starting to build speed, and everyone was on the same page. There was still that fresh, new energy there. Then Covid hit and we shut down for seven months,” recalls Story.

A Coldharbour venture

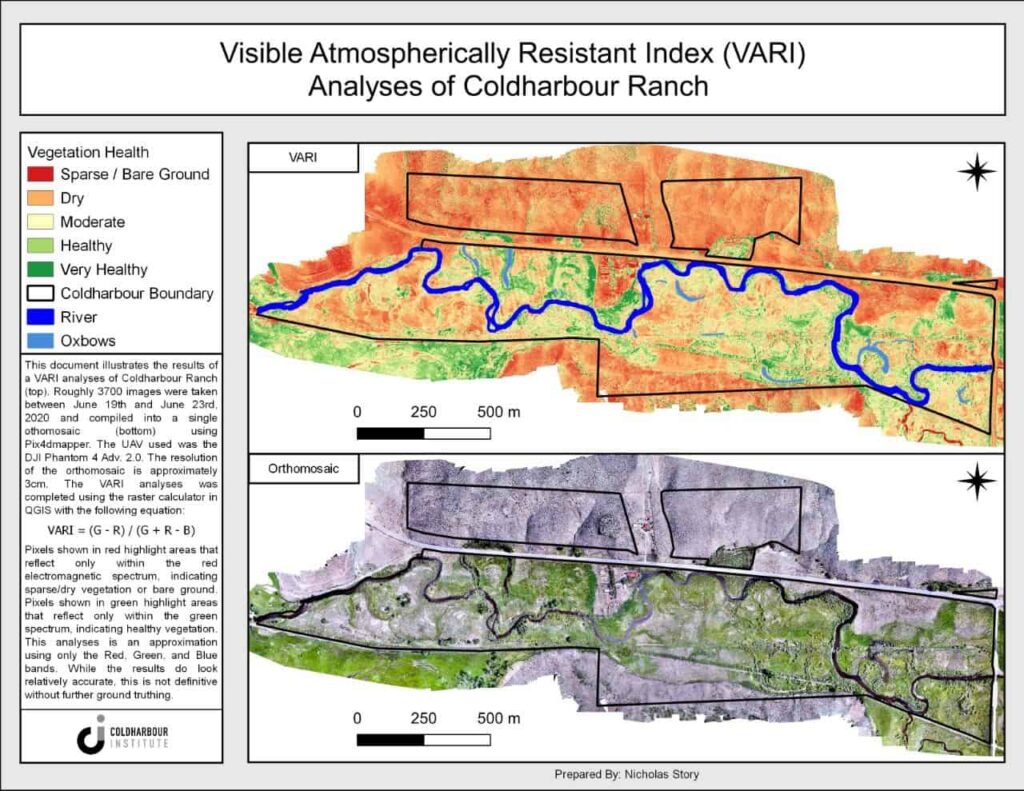

That exodus, and his subsequent move to Gunnison, allowed him to pursue an area of passion he had toyed with for years: drone mapping. “I saw how great the imagery came out. What a great utility it [had], and I enjoyed doing it,” he says.

Story spent his pandemic layover—roughly half a year, back in Gunnison—and found an eager project partner for his drone work in Coldharbour Institute.

Coldharbour is a 334-acre ranch, nonprofit, and “living laboratory” located just 7 miles east of Gunnison that has fostered a tight relationship with Western and Clark Family School of Environmental and Sustainability (ENVS) students.

Story recalls listening to the previous MEM cohorts’ end-of-year forum, where students present their project work in dissectable, 10-minute chunks. One of the students, who had worked with Coldharbour for their project, noted that there was a gap in knowledge surrounding the property’s physical geography.

So, Story used the spare time between his Nigeria stints to map out the Coldharbour property, stitching together 3,500 distinct images which allowed him to put together 3D models of the land. He also worked on mapping invasive species on Coldharbour land, venturing out with a GPS camera and documenting the property’s invasive thistle.

Additionally, Story started to work with Dr. Micah Russell, an ENVS professor, to assist with creating a more formal drone education program for Western. He aided in the purchase of a “super computer” that MEM acquired to process drone and GIS imagery in 2021.

In the time Story spent in Gunnison, he found plenty of good work to occupy his time, but the evolving response to the pandemic made his return to Nigeria feasible in the late fall of 2020, so he headed back to continue his work on the remediation project.

Heading back to Bodo

Shortly after his return, Story found that continuing his schooling online while working full-time on the ground was no longer tenable. “At that point, I got burnt out—I couldn’t do both at the same time with the time difference…it was just too much,” he remembers, so he opted to put graduate school on hold until the project’s completion.

In his time in the Niger Delta, Story has soaked up knowledge about the importance of mangrove ecosystems. Story notes the ecosystem’s broad utility in providing habitat and water filtration services, but also as sources of timber and firewood for local peoples.

“[Mangroves are] a big buzzword. Everyone’s all about mangroves these days, and I just happen to be working with them,” says Story with a chuckle, who notes the inherent hardiness of the species.

Even so, the BMI has opted to plant mangrove seedlings rather than seed pods, a safeguard against other possible spill events because the seedlings are taller, and their leaves stick out above the high tide, limiting their potential exposure to oil or other waterborne threats.

Despite the setbacks for the pandemic and the managed chaos of coordinating diverse stakeholders on a huge environmental restoration project, Story is incredibly proud of what the BMI have accomplished. They have witnessed the products of their continued labor—the delta environment, and particularly the mangrove habitat, is starting to spring to life.

“When I arrived, there were still illegal refining operations in the area, spilling oil directly into the creeks,” says Story. Now, the illegal refining operations have been halted, and the remediation work is well underway, with more than 330,000 mangroves planted thus far, and more to quickly follow when the major planting contracts are secured—more than two million in all when the project is said and done.

The project, operating at full speed, is slated to wrap up the environmental remediation phase by the end of 2022 and the mangrove planting shortly thereafter. While the remediation work will then be finished, ground monitoring of the mangroves will continue for three more years to ensure the planting program functions properly, followed by an additional two years of monitoring via remote sensing.

Story adds that it has been a pleasure to serve as SCAT Team Leader, working with a group of dedicated stakeholders, and serving as a site host to UNEP, non-government organizations (NGOs), the Hydrocarbon Pollution Remediation Project (HYPREP), and visitors from oil companies.

He also had the opportunity to present a research poster at the International Oil Spill Conference in May 2021, and two articles he co-authored regarding the project—one on the use of remote sensing to estimate mangrove regeneration in Bodo, and the other concerning the technical aspects of the cleanup efforts—are in the peer review process.

Story’s future

Eyeing life after Bodo, Story is interested in founding a drone mapping venture with a friend, but he notes that his vision for the future has shifted during his tenure on the Bodo project. “Being in Nigeria, my goals have changed. It’s very interesting to be on the management side of things—being at the table.”

To that end, he has been offered a position in a neighboring project that would find him continuing work on the effects of the same oil spill— an offer he is considering.

Story is also exploring the prospect of further education—a Ph.D perhaps— in a field like conflict management or environmental policy that would situate him to work on international environmental issues that span many different stakeholders, and involve conflicting values.

He finds that he is drawn to more complex and conflict-prone environmental issues, both as a matter of excitement and as the result of a natural skill set in working through tensions. “I think I’ve always been somewhat of a mediator,” Story adds.

He recalls being kicked out of high school at 16, and taking a trip shortly thereafter with a humanitarian group to Honduras, where the team doled out medical aid in the middle of the rainforest. “That right there is maybe the reason why I’m here,” adds Story, who has made humanitarian work a staple in his life.

For now, Story is focusing on finishing the Nigeria project—often working seven days a week—and browsing jobs in international aid, disaster planning, and other similar fields to gauge the market, and his interests, in his free time.