“The first [time] I came up with the study was when I was getting no sleep when my daughter was born, in April 2021, and this idea came [to me],” says Clinton Cole, an Exercise and Sport Science (ESS) graduate student who studied the impact of sleep intervention on NCAA athletes for his research project. Back in his undergrad, Cole ran sprints on the Track team for Incarnate Word (UIW), a private, Division I school in his home state of Texas.

While at UIW, he picked up a degree in Kinesiology and a minor in Education in pursuit of a prospective career in coaching. Cole’s Track coach at UIW, a former teammate of Lindsey Grasmick, head Track and Field coach at Western, led Cole to enroll in graduate school at Western.

As a Graduate Assistant Coach for sprinting and jumping at Western, Cole provides mentorship and guidance for the team’s athletes, a role he began back in 2020. While pondering the focus of his second-year research project, Cole noticed a trend within the team. “I noticed a lot of [team] fatigue and hearing a lot of the athletes saying they’re fatigued,” he notes.

Cole decided to craft a study that examined fatigue and sleep amongst the Track and Field athletes, based on the literature examining athletic performance and sleep habits. “Who wouldn’t benefit from coming in at two or three in the afternoon taking an hour nap or two-hour nap?” Cole asks.

The study participants, members of the Mountaineer Track and Field team, were divided up into two groups: control and experimental. Experimental group participants were prescribed twice-weekly, hour-long “treatment” naps taken over the course of a month and evaluated in several areas of their life: academics, athletic performance, and overall mental health and wellbeing.

To make the study’s comparisons, Cole cross-referenced the student athlete’s 2021 and 2022 grade point averages (GPAs), ran the athletes through a pre- and post-study timed 10-meter dash, compared their 2021 and 2022 meet results, assessed changes to sleep quantity, quality, and excessive daytime sleepiness (i.e. dozing off in class), and inquired into participant’s anxieties surrounding their sleep habits.

Several athletes reported that the study’s naps boosted their energy for practice and stated a desire for more naps. Statistically, Cole saw the study’s experimental group gain .2 hours of average sleep over the course of research, and that increased sleep length appeared to trickle over into better grades and performance, including faster 10-meter dash times.

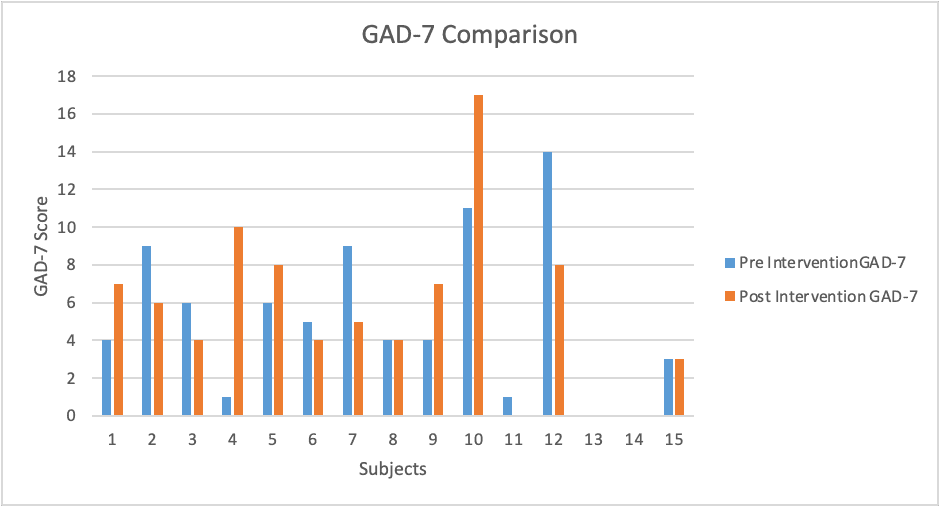

Interestingly, both the experimental and control groups were able to reduce their self-reported anxiety over the study’s course.

Cole adds that the study is ripe for a transition into nonathletes in the future, hypothesizing that the structure provided by the study’s nap would allow the general student body to boost their GPAs by instilling more rigidity and structure in the student’s schedules. “You’re going to be a lot more focused, you’re gonna be a lot more awake [post-nap],” he adds of the benefits of a midday siesta.

Cole adds that while he was overseeing his study, his own sleep was not always up to snuff. “The study was contradicting [with my own life] because I did work overnights, and I had a newborn child. If I could be a part of the study, I would love to,” he adds with a chuckle, before encouraging a future student to pick up and build upon his study.

Looking ahead, Cole is interested in pursuing personal training with a mind towards practicing exercise physiology in a hospital setting, helping patients fulfill their exercise “prescriptions” to meet their physical and wellness goals. He is also considering options to attend further his education to become a physician’s assistant (PA) or pursue a doctorate degree in sports psychology.