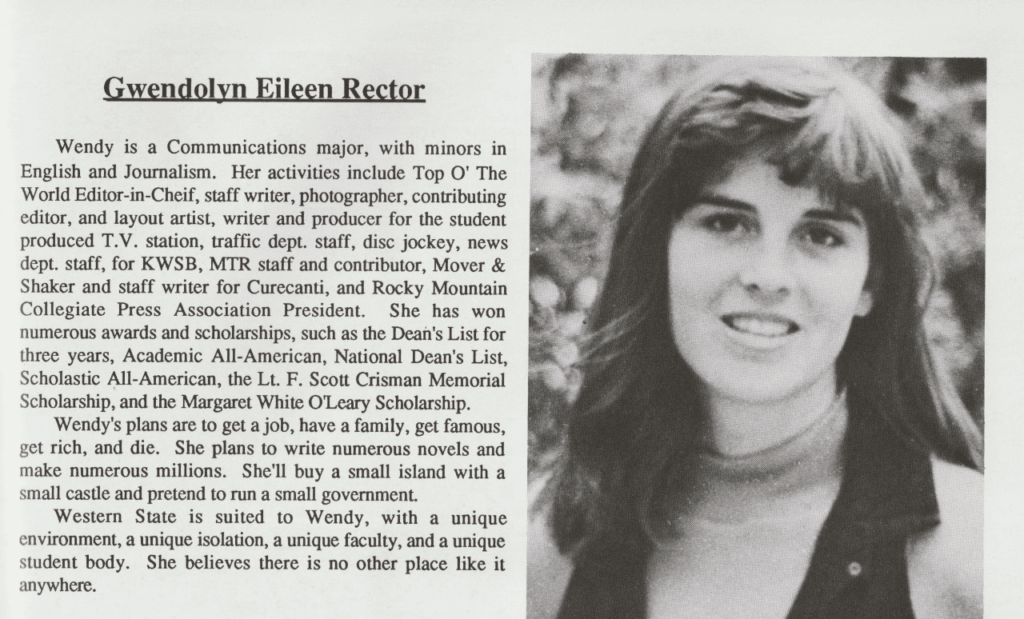

“It was crazy that I could get involved in everything [at Western] … so I did and I was having the time of my life,” recalls Wendy Rector, who served as editor of Top o’ the World in 1986-87.

When Rector first came to Western as a transfer student studying communications, she discovered a wealth of possibilities to get involved on campus, and quickly became a fixture of the university’s media clubs and organizations — Top of course, but also the annual Curecanti Yearbook, the Mountain Thought Review literary magazine, and KWSB student radio.

In her first year at Western, she hosted a KWSB radio show that ran from midnight to 3 a.m.

On the airwaves, Rector was known by the DJ callsign “Gwendolyn Wild.” During her shows, she cued up a healthy dose of Grateful Dead and the progressive rock band Yes for late-night listeners.

One night, she went outside to usher in the next DJ at 3 a.m., accidentally locking herself outside out. Meanwhile, KWSB was broadcasting the repeated “de-dunk” noise signaling the conclusion of that particular Yes album (the station could only play physical albums then), and Rector was left to frantically attempt to gain entrance into the building in the midst of a frigid Gunnison winter night.

The next year, Rector moved on to other media and artistic pursuits, but remembers a rift developing between KWSB and Top, largely centered on the newspaper’s critical coverage of the radio station’s mismanagement of funds — which included splurging for new equipment and then threatening to go off the air.

“It wasn’t a great relationship, even though half of [the Top staff] or more were DJs the previous year,” she says.

Assembling a news team

Rector recalls being urged to become the newspaper’s editor her second year at Western, and quickly assembling a ragtag team of journalists that would coalesce as the year went on.

“The hardest part was being in charge of a weekly newspaper without really knowing what I was doing [at first],” she offers. “I had a bunch of writers who had never written before, so I had to sit down with them and edit their stories and make them publishable.”

But in short order Rector would find herself thriving at the helm of a functional, bustling student news operation — and enjoying the mentorship aspects that accompanied the editorship.

“The writers got better and better … it was so amazing to watch people find their voices, and that really had a great impact on me,” she adds.

Rector notes that the Top o’ the World was being advised then by professor Charlie Miller, who gave the students the freedom they needed to take real ownership over the paper, while providing the guidance the budding journalistic team needed to thrive.

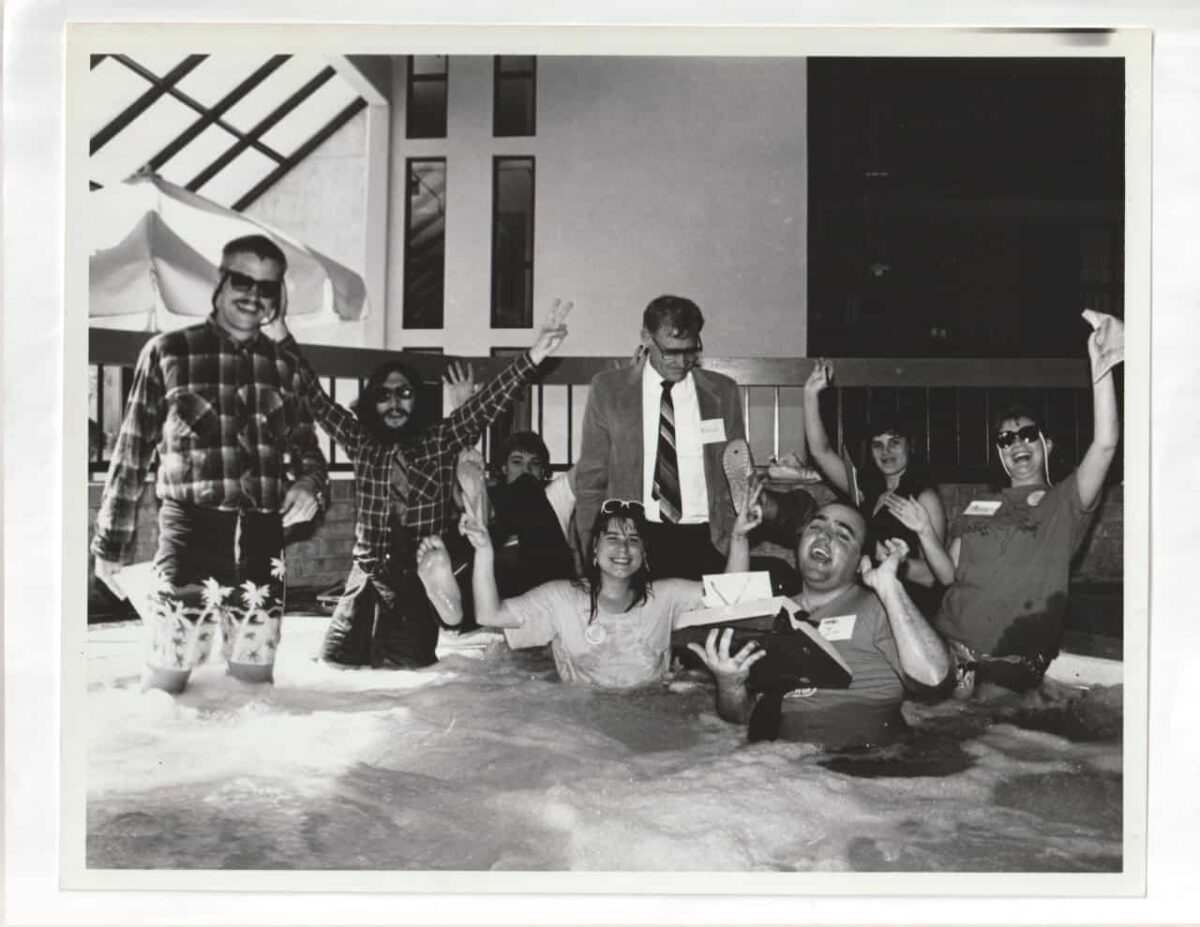

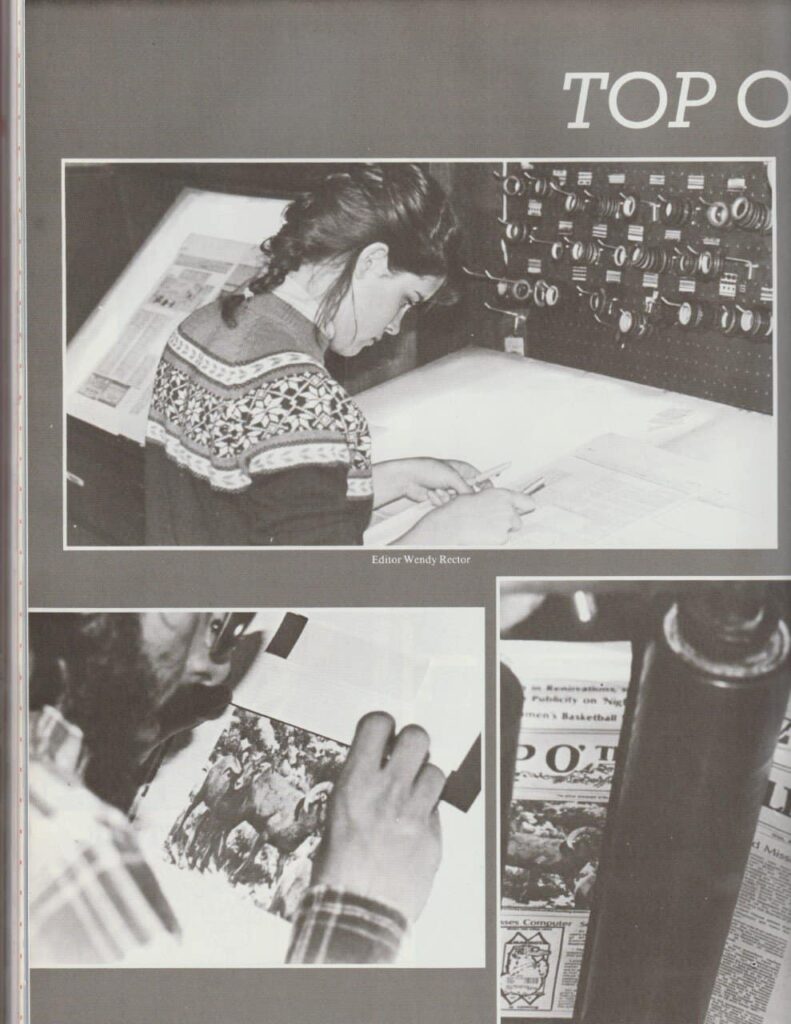

She remembers a lot of late nights spent writing, editing, and physically, painstakingly assembling the latest edition over at the Gunnison Country Times’ office, where the student newspaper was printed each week.

“It took us forever to do everything by hand. I remember coming home late at night with words and tape and paragraphs all over my shoes — and wax, because we had to wax it all together.”

Those late nights aided the process of forging a cohesive newspaper team.

“We’d stay up late and talk about politics and what was going on with the world and we kind of caught the journalism bug. We wanted to change the world,” Rector says.

Engaging Western’s campus on the issues

Wendy cites Dave Cuomo, the paper’s assistant editor, and Dave Benston, who became the news editor in the spring of 1987, as top-notch writers with a penchant for political coverage.

The duo covered president Ronald Reagan’s busy second term, including major flashpoints like the administration’s 1986 bombing of Libya and the onset of the HIV/AIDS crisis, which was first discovered in 1983.

Much of Top’s coverage came in the form of critical columns designed to engage with students and provoke debate on campus. Rector says that these entries were met with a variety of feedback — ranging from support to a barrage of conflicting letters to the editor — and all the way to outright hate mail.

“It was great because we had a lot of engagement,” she says. “We really were all about urging students to become involved.”

At the state level, Top o’ the World staff was keyed in on Colorado’s budgetary issues, which included cuts to higher education spending that trickled down to impact Western’s bottom line.

The paper in those years had a liberal bent, but the staff retained their journalistic integrity and took great pride in the work they were churning out on a weekly basis.

All the while, Wendy was learning how to manage a team through the ups and downs of the newspaper world — taking the brunt of any criticism resulting from Top’s coverage, writing the stories no one else wanted, and altogether burning the candle at both ends to make weekly publication possible.

When she first assumed the role of editor in the fall of 1986, 21 students were listed as newspaper staff. By the spring of 1987, the total Top personnel count had ballooned to 38, and the newspaper was humming along nicely.

“Not sure what they all did, but we were definitely gaining momentum,” Rector told me via email.

Top gains acclaim — and imitators, too

Top’s professionalism under Rector earned them the respect of J.W. Campbell, Western’s information director. Her senior year, Rector would go to work for Campbell’s office, where she helped write university releases and the script for an award-winning recruitment video.

Despite some pushback and unease towards Top o’ the World from Western’s administrators over certain stories, Rector says the paper’s efforts were always intended to push for positive change on behalf of students. Across campus, the newspaper was largely held in high regard.

Top’s efforts resulted in a group of young Republicans at the university starting an opposition publication called “The Alternate”, which aimed to directly counter stories published by Rector and her crew.

“They spent their own money doing it, and they could have just written letters to the editors and we would have printed them,” says Wendy with a laugh, noting that nearly all of the paper’s work was unpaid at the time. “They could have taken over if they wanted.”

She remembers writing one piece where she advocated for doubling down on the university’s strengths — its unique and strong competitive skiing program, for one — and the ski resort up in Crested Butte (then family owned), which Rector suggested giving students free passes for. Recreational skiing has been a major recruiting draw for Western since the 1960s.

In that same column, she called for less money to be funneled towards the school’s football team, which at that time was rather mediocre. For her efforts, she found herself escorted out from a campus party to protect her from some unamused football players.

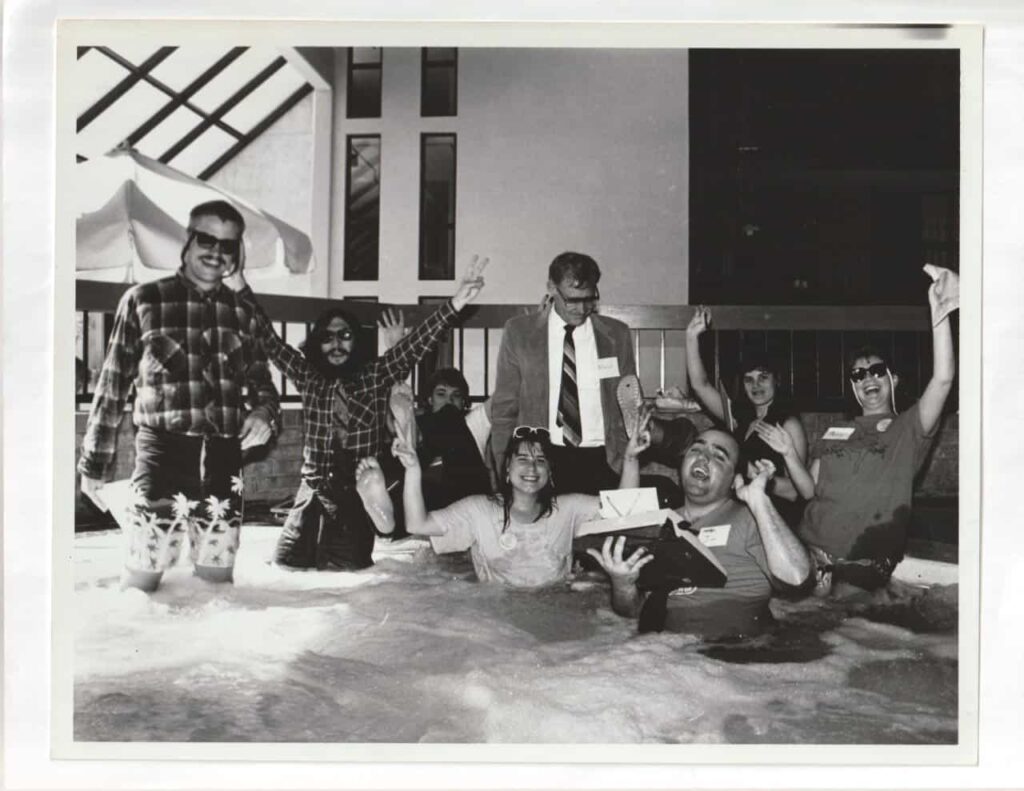

In the spring of 1987, Rector and her staff traveled to the Rocky Mountain Collegiate Press Association annual convention in Odessa, Texas, a gathering of collegiate newspapers hailing from 14 different western states.

At the regional conference, Top o’ the World was recognized with a number of newspaper awards and student reporters had the chance to compete in a variety of live journalism competitions.

The following year, Rector became the president of the press association and was in charge of hosting more than 300 student journalists in Gunnison in March of 1988.

At that year’s convention, students covered live debates and speeches from various local and state politicians in real time — including written and broadcasting elements.

“There was a difference between broadcast people and print people,” says Rector. “The broadcast people are all big personalities .. and the print people are all these kinda weird, nerdy intellectuals who wrote about ideology.”

From left, back row: Sean Herrin, Dave Cuomo, Dave Benston, J.W. Campbell, Wendy Rector, Shelly Ostwald. Front row: Becky Bush, Jim Hoffman.

Life after Top o’ the World

Immediately after graduating, Rector spent a year working up at Crested Butte, before decamping to Oregon and working for a small newspaper, The Bee, which covers parts of southwest Portland.

During her time at the local outlet, Rector was solely responsible for the entirety of the paper’s writing, editing, and photography.

After leaving The Bee she pieced together a series of writing and marketing jobs before going on to earn her master’s degree in Liberal Arts from Reed College in Portland, Oregon.

Similar to other featured editors John Cunningham and Yvette Roberts, Rector so settled into a career as an educator, and spent more than two decades teaching high school in Colorado and in Portland, Oregon.

Both Daves from her staff also found their way into the educational field — Benston now works as an IT director for a school district in the southern Portland metro, while Cuomo works in astronomy education and programming.

“I loved the classroom and I love debating issues with students — learning from them and teaching them how to improve their writing, their analytical and research skills, and just opening up the broader world to them,” says Rector.

Over the course of her teaching career, she taught topics as varied as film, journalism, literary artistic movements, and mythology.

“I used everything I learned at Western — I advised school newspapers, I advised the [high] school yearbooks, I directed student drama productions, I coached the girl’s and boy’s varsity soccer teams. My kids won awards, they got published in the outside world, they went to college — they did all these wonderful things,” says Rector. “That was the best part of my job, hearing all of these wonderful things that my students had done. It gave me purpose.”

Wendy advised the high school newspaper in Fairplay the year that the popular animated show South Park, which is based on its creators memories of real life locations in the town, debuted on Comedy Central.

“We got a lot of national attention, and not all of it was good,” notes Rector. “I had my student news editor call Comedy Central and tell him that we actually were a real place. Comedy Central had no idea.”

The summer after the show’s debut, staff from Comedy Central came out to Fairplay to film the town for segments that later ran between the show’s episodes.

In retrospect, Rector can partially trace her career path, and its underlying pursuit of purpose, back to her time at Top’s helm in the 1980s.

“It taught me that I could change the world — in small ways,” she says.