Western’s newest graduate program, the Rural Community Health Master’s of Behavior Science (MBS), which emphasizes holistic community and behavioral health, strategic prevention, and place-based education, is set to graduate its first two students this May.

Samantha Coleman and Spencer Smith are both wrapping up community projects designed to better understand and improve mental health on Western’s campus, and within the greater Gunnison community.

For Coleman and Smith, the hyper-intimate class setting, usually just the two of them with a professor, fostered both personal and academic growth as the pair seek to carve out a career within the growing field of mental and behavioral health.

With that miniature class size comes a personalized, hands-on education.

“You have to answer questions,” says Smith with a laugh. “There’s no hiding … I’ve learned so much from that. You have to be engaged.”

Both Coleman and Smith first came to Western, in large part, for athletics — but both have earned their undergraduate degrees and decided to pursue additional education at Western, rolling the dice on an entirely new program — a gamble that’s paid off in spades.

Understanding student needs

Since 2017, Coleman has been a staple of the women’s basketball team, starting more than 100 games and racking up more than 1,200 career points before completing her sociology degree in 2021.

This past year, Coleman served as the university’s director of basketball operations, where she organized team trips and itineraries, crafted experiences for players, and assisted with day-to-day coaching, drills and development.

Coleman also serves as the resident director for Ute Hall, overseeing more than 140 students, organizing activities, helping plan curriculum, and mediating conflicts as they arise.

She initially came to the MBS program for personal reasons surrounding mental health, family, and trauma within her past.

“It just hit home for me that what I want to do is help people,” she explained.

When considering what to do for her practicum, Coleman was influenced by a number of student deaths at Western during her tenure, including several instances where Mountaineer students died by suicide.

“We don’t have a mental health advocate for student athletes primarily,” said Coleman, who set out to make it easier for students to understand and access the resources available to them.

Coming from Las Vegas, Coleman admits the transition to the much more rural Gunnison was somewhat of a shock — one that often poses issues for new students as they try to make sense of a small, remote mountain town.

Sensing the need to understand the resource and knowledge gap, and to provide personalized guidance, Coleman created a mental health resources screening for her second-year practicum, utilizing the strategic prevention methods and survey techniques she has learned at Western.

She first piloted the questionnaire with the incoming cohort of student athletes back in the early fall.

Her screening seeks to understand existing student beliefs and stigmas around mental health, their knowledge of available resources at Western — and in Gunnison.

Then, she asked students if they would like to be connected with specific resources, like Western’s Counseling Center, Crested Butte State of Mind, and the Gunnison Country Food Pantry, which recently opened a satellite location in Western’s library.

In the midst of the fall semester, the updated questionnaire was sent out to all first-year and transfer students who entered Western in the fall of 2022. Later, Coleman followed up individually with participating students to dole out information about resources they had expressed interest in, connecting them to the broader community.

After that follow-up, Coleman sent out one last missive, which contained a second survey analyzing if students’ stigmas and attitudes towards mental health had changed over the course of the process and asking for feedback on the project. That feedback came back extremely positive.

Many new students expressed interest in being connected with counseling services at Western, although Coleman notes that one potential setback to accessing counseling resources is the center’s location — inside of Tomichi Hall, a freshman dorm.

Because of that location, the potential for students to perceive social stigma while attending sessions is high.

“It’s difficult for students to feel like it’s confidential,” said Coleman, who believes that stigma may play some role in dissuading students from seeking professional help.

Another option available for students which can be accessed remotely is TimelyCare, where students can schedule therapy appointments or talk to a provider 24/7, on-demand.

Moving forward, Coleman would love to see the survey continue and expand to include a physical healthcare component.

Altogether, Coleman, who hopes to play basketball overseas this summer, is grateful for the MBS program, which has imparted her with a wide range of skills — and stoked previously passions in working with adolescents and brain development.

“This program has really taught me the ins and outs of research, and what it’s like to be a researcher,” said Coleman.

In the immediate future, she is looking forward to relaxing and taking time off to explore after presenting her project and completing her master’s.

Stepping up to destigmatize suicide

Fellow Mountaineer Athlete Spencer Smith came to Western from his native California after pondering an offer to play football for the Naval Academy.

He played five years as a tight end for the Mountaineer football team, and was named to the RMAC’s academic honor roll.

More recently, Smith, who graduated from Western in 2021 with a double major in sociology and psychology, has served as a success advisor out of the Academic Resource Center (ARC), working one-on-one with a cohort of mostly sociology students to help boost their academic performance via time management practices and improved study skills.

For Smith, Western’s MBS program fit his desire to practice social work, delve deeper into the field of behavioral health, and extend his football career through the 2021 season.

Completing graduate work in the program has opened his eyes to the difficult realities facing rural communities regarding healthcare access and the unique struggles that rural settings pose.

Those challenges, he says, include “less access to health care (whether that is due to smaller population size or far distances to receive care), workforce shortages, higher rates of substance use, risky behaviors, and some chronic health problems such as high blood pressure and obesity.”

Layered on top of these systemic factors is a stigma against seeking mental health care, a factor many people associate with an ingrained identity of rugged individualism, particularly in rural portions of Rocky Mountain states.

Choosing a practicum — the required project for MBS students, initially proved difficult for Smith, who has many areas of interest within the realm of rural health. After some consideration, he zeroed in on the field of mental health.

“I think something that really influenced me was the suicide last year on campus of a student athlete,” said Smith. “He was a friend of mine. That just showed that this was a huge concern … something that just needed focus.”

The safeTALK program

So Smith set out to address suicide head-on with a preventative program. After a series of meetings with county health officials, Western faculty, and others, Smith decided to facilitate a series of one-day, roughly four-hour suicide prevention trainings known as safeTALK, a program of LivingWorks.

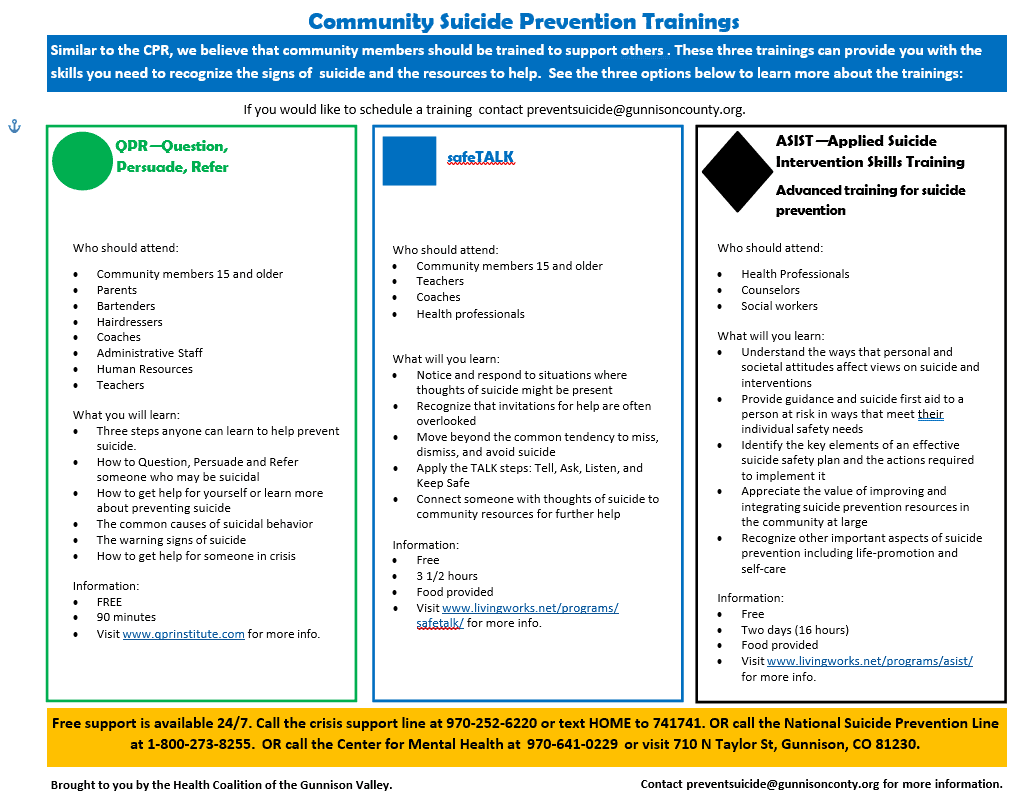

Other popular suicide preventions include the Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) curriculum administered by the QPR Institute, a 90-minute training which can be accessed online via the institute’s website, and is often offered through Western.

On the more intensive end is ASIST, a two-day, 16-hour program largely intended for healthcare professionals and counselors that proves additional practical intervention skills.

Smith settled on the safeTALK program, an interactive course which emphasizes boosting suicide awareness, identifying when suicidality may be present, and learning about the TALK steps: Tell, Ask, Listen and Keep Safe.

He scrounged up the funds to travel to Seattle, Washington to attend a three-day, intensive course to become a certified trainer.

Starting after the holiday break, Smith facilitated four on-campus trainings for a mixed crowd of Western students, faculty, and staff this spring, with the last training taking place in early March.

“safeTALK’s [mission] is creating people who are aware of suicide,” says Smith, who references “invitations”, signs that someone who is currently experiencing suicidal ideation may be contemplating ending their own life.

Once a person has recognized prospective suicidality, the next step is to ask the question directly: “Are you having thoughts of suicide?”

Years of evidence-based research has emphasized the importance of asking that question outright — not couching it in euphemisms or asking more generally about a person’s mood.

“If you’re going to ask this question: ‘Are you having thoughts of suicide?’ then is there a chance that you are giving this idea to them?” asks Smith, assuming the mentality of a safeTALK trainee.

No, he reassures us, adding: “Humans just aren’t that easy to convince like that. For you just to ask a caring question, it doesn’t create [thoughts of suicide],” he says — an assertion that is backed up by the best data available.

Once the question has been posed, the resulting answer helps the practitioner narrow in on what to do next.

If it’s a no, that allows the questioner and the respondent to move on to addressing the underlying issue — whatever that may be.

If the answer is a yes, that opens the dialogue in a different direction — hearing out the individual while remaining on the scene.

“You make sure that whatever happens next you’re going to be involved,” says Smith. “You don’t promise any secrecy after that — you let them know that we’re gonna seek help together.”

Upon seeking that formal help, Smith notes that the research shows that suicidal ideation often abates.

“You can truly save a life,” says Smith, who emphasizes how easy it is to make excuses and write off the possibility of suicidal thoughts and intention.

There’s this really common narrative that “you never would have seen it coming with this guy, or this girl,” but programs like safeTALK allow people to make a material difference in their communities, and to move beyond the feeling of helplessness.

Through a series of presentations and videos, safeTALK training empowers students to follow-up on the suicide question, referring resources to individuals who are experiencing suicidal thoughts — and keeping the individual safe in the interim.

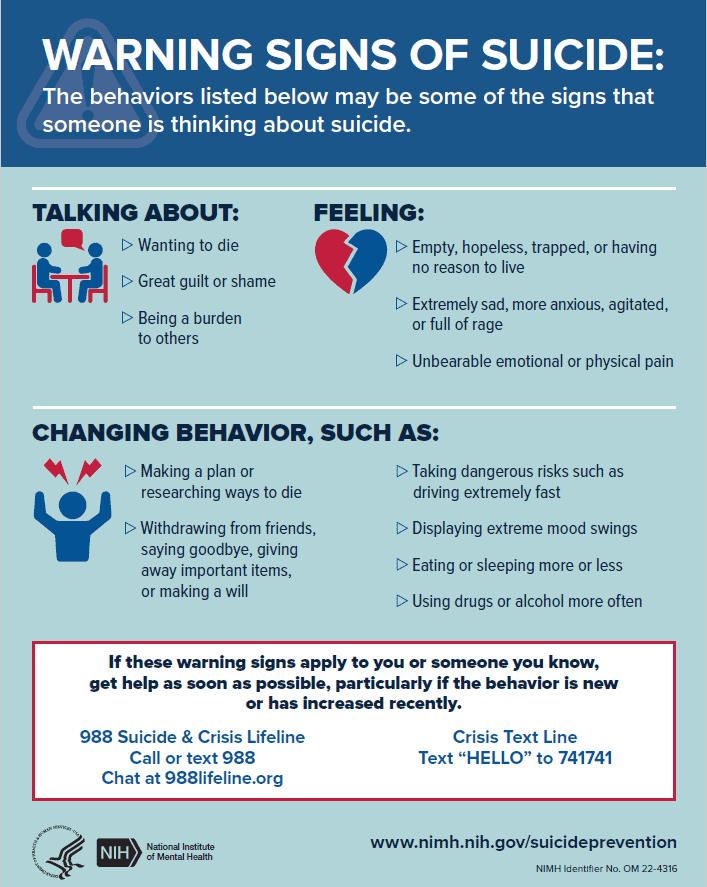

One of Smith’s favorite portions of the course involves group brainstorming on how to more effectively communicate with community members, and to become more aware of the telltale signs of suicide (pictured below).

After enabling students with a number of tools, the course culminates in a 30-minute roleplay scenario where students have the opportunity to embody different individuals whose backstory is laid out on a card — rotating between characters as they learn to directly ask an individual about suicidal thoughts.

In the roleplay, participants have the chance to experience the other end of that painful but necessary conversation.

“It’s always super fruitful,” says Smith. “It creates really good conversation and shows how difficult it can be, but also how easy it can be to ask the [suicide] question and get it off your chest.”

At the end of the training, Smith says that many attendees will start contemplating and reflecting on their own life, identifying situations where there may have been individuals wrestling with suicidal thoughts who could have utilized more support in those vital moments.

The road ahead

Seeing his series of spring trainings fill up has been affirming for Smith, who knows that some students — and others in the community — may be struggling, particularly in the long winter months in a remote mountain town.

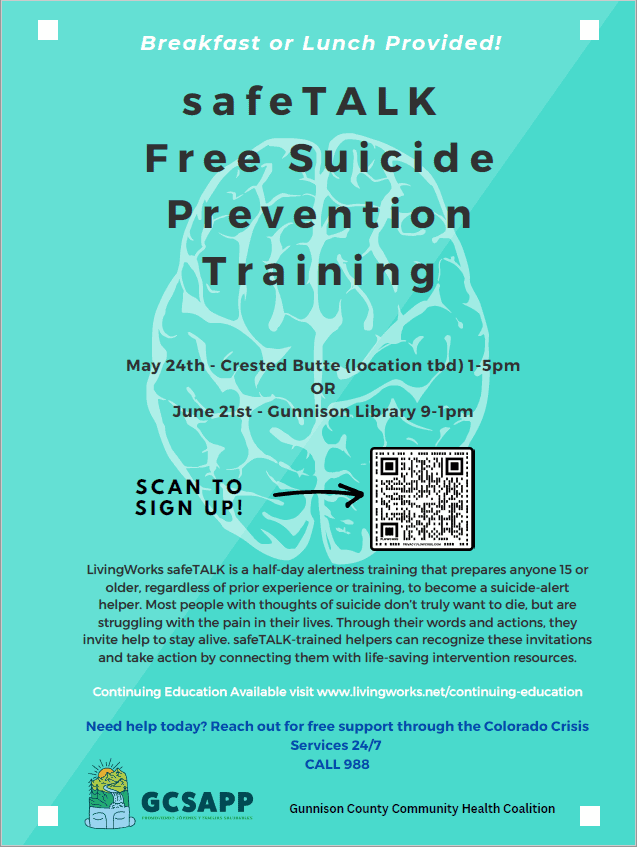

And for students and others sticking around town over the summer, Smith will be hosting two more webinars, May 24 in Crested Butte (1 to 5 p.m., location TBD) and another to be held on June 21 (9 a.m. to 1 p.m.) at the Gunnison Library.

Stepping back, Spencer can’t recommend the nascent MBS program enough, adding that the coursework has helped him attain skills in sensitivity and language, knowledge of how oppression impacts health and healthcare, and the avenues available to approach and connect with people on a human level.

With this newfound knowledge, he hopes to work in behavioral health — possibly in social work, or with a health-based nonprofit.

Altogether, Smith is feeling positive about the state of mental health resources, and the direction the Gunnison community is taking.

“Compared to when I first got here six years ago, there are so many more opportunities to seek mental health assistance,” he concluded.

Coleman and Smith’s project presentations, presented in the first-ever Western Community Health Forum, can be seen on Tuesday, May 2 at 12 p.m. in Kelley 229, or via the QR code on the flier.