By Courtney King

After decades of protesting against potential mining operations on Mount Emmons, commonly referred to as Red Lady, recent protection of the area served as a long-awaited sigh-of-relief for many in the Gunnison Basin.

Recently, I spoke with Julie Nania, Red Lady and Water Program Director at High Country Conservation Advocates (HCCA), an environmental nonprofit based in Crested Butte, about the progress that has been made to “Save Red Lady,” and legislation that HCCA is pushing for to further protect Mount Emmons.

Ranchers, recreationists, radicals, and Red Lady herself — all that and more illustrated in a poster for the film “High Country,” which recounts “a timeless American story of how a community of conscientious and forward-thinking young people, disguised as ski bums and hippies, happened upon a ramshackle mining town on the fringe of society and worked to conserve and protect it for years to come.” The movie was recently shown in Boulder and Salt Lake City.

The history of Mt. Emmons

The controversy around Mt. Emmons first began back in 1977, when a multi-national mining corporation called Amax announced its intention to mine for molybdenum, beginning a wave of creative protests including parties and “Red Lady Salvation Balls.”

The mayor at the time, W. Mitchell, raised awareness of the struggle to preserve the mountain among state and country officials — sowing seeds that would prove to be invaluable decades later. In 1981, protest parties transformed into celebrations as Amax announced they would be foregoing their plans.

The fight was chronicled by local journalist Paul Anderson. In a review of Anderson’s book, famed wilderness historian Roderick Frazier Nash wrote, “The environmental movement consists of victories in many small battles. ‘The Town That Said Hell No!’ is about one of the most dramatic. The mining company walked away and even the pro-mine locals learned they really could ‘eat scenery’.”

Protests haven’t ended, however, as once Amax left a revolving door of subsequent companies tried and failed to mine the area for decades. The issue came to a head nearly 40 years later, when in 2015 an Arizona-based molybdenum mining company called Freeport McMoRan (and its subsidiary, the aptly named Mt. Emmons Mining Corporation) came to town.

The company had a different plan than previous failed proposals, however, offering to take responsibility for the mine water treatment plant and find a way to mine the area’s minerals that would not involve Red Lady herself, but surrounding lands.

In 2016, the Town of Crested Butte, with the backing of local voters, approved $2.1 million in bonds to be paid to the Mount Emmons Mining Company, extinguishing over one thousand unpatented mining claims north of town.

It was around this time that Julie Nania, who serves as HCCA’s water director — and one of several lawyers on the nonprofit’s staff — arrived in the valley.

Formerly a faculty member of the University of Colorado Law School, Nania had predominantly worked with tribal governments on issues surrounding federal reserve water rights.

She had first heard about Crested Butte from one of her own former professors, Roger Flynn, who had been one of the long-term attorneys focused on Mt. Emmons. Nania leapt at the chance to continue that work with HCCA’s water program, which was increasingly focused on staving off Freeport McMoRan’s efforts to mine Mt. Emmons.

As the fight to save Mt. Emmons carried into its fourth decade, HCCA was looking to recruit the next generation of citizens to fight for Red Lady, the foundational issue that spurred the nonprofit’s initial creation in 1977, known then as High Country Citizens’ Alliance.

In her current work, Nania draws on combined expertise in public lands, mining, and water law as she negotiates the easements and water quality concerns associated with Red Lady.

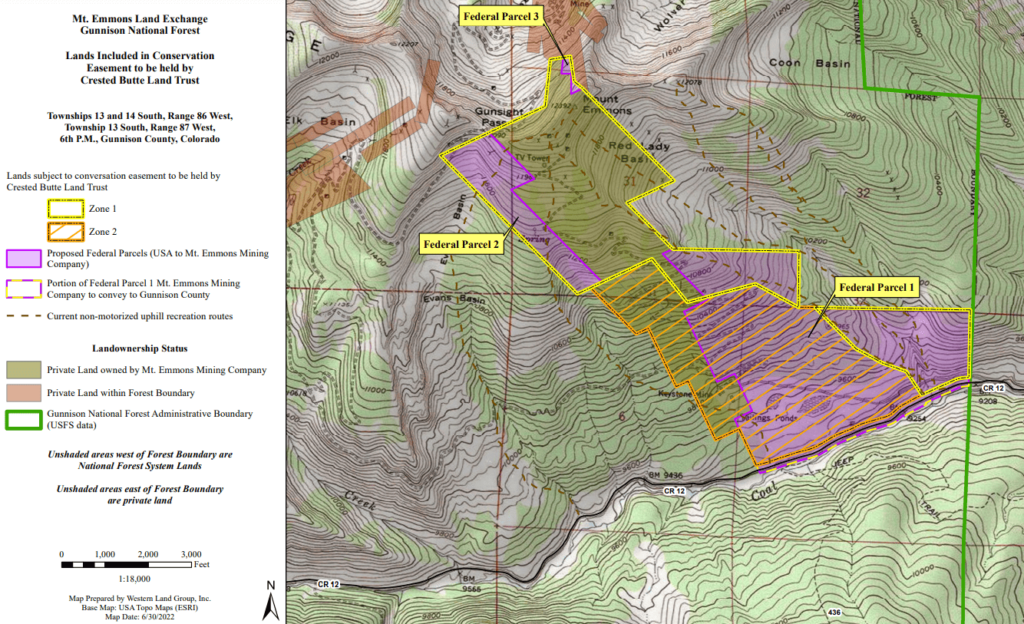

In February 2021, Nania, working in concert with Roger Flynn, an attorney for the Western Mining Action Project, struck a deal with the Mt. Emmons Mining Corporation, which applied for a land trade with the U.S. Forest Service.

The finalized deal would protect the headwaters of the Gunnison River, allow recreation like hiking, biking, and skiing to continue on Red Lady, and would provide the company with other lands on which to mine, roughly 650 acres spread across four areas in Gunnison and Saguache counties.

Turning the tide for the Red Lady

A year later, the decades-long struggle to stave off mining efforts was rewarded when the Biden administration began the process of considering and potentially implementing a 20-year mineral withdrawal.

Perhaps overshadowed in some parts of Colorado, as the decision was announced during the ceremony to designate Camp Hale a new National Monument, the withdrawal was cause for celebration in Crested Butte.

Nania believes that the intensity of public participation in support of preserving the Red Lady carried significant weight with state and federal officials involved in the withdrawal decision.

Additionally, Mt. Emmons presented a unique opportunity for the interests of land management agencies, conservation organizations, and mining companies to be represented.

Other collaborative, multi-stakeholder public land management processes like the Gunnison Public Lands Initiative (GPLI), which was introduced as the GORP Act in 2022, have provided further backing for the area’s protection, as have the simple fact that recreationists and ranchers alike are fully on board.

After the declaration at Camp Hale, the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service submitted a joint withdrawal application to Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, which was later approved.

That federal decision prohibited new mining claims and federal mineral leases in the Thompson Divide area, but only for two years while further environmental analysis was prepared for a potential 20-year withdrawal.

The move was a step in the right direction for Crested Butte conservations, but not enough in the eyes of dedicated locals, who’ve been waiting more than 45 years for a final resolution in favor of conservation.

The fight rages on

As federal agencies started their review, locals buckled down and continued to wage the decades-long fight, which has seen numerous iterations of mining corporations come and go.

Sen. Michael Bennet, who has worked on the Gunnison Public Lands Initiative since 2012, ensured that protections for Red Lady would be included in the Colorado Outdoor Recreation & Economy (CORE) Act.

Back in May, the usual trio of Benett, Sen. John Hickenlooper, and Rep. Joe Neguse reintroduced the bill, first proposed back in 2019. The CORE ACT, which includes protections for more than 400,000 acres of land in Colorado, has passed the House of Representatives five times, but has always stalled out in the Senate.

The act combines four bills: the Continental Divide Recreation, Wilderness, and Camp Hale Legacy Act; the San Juan Mountains Wilderness Act; the Thompson Divide Withdrawal and Protection Act; and (also quite locally relevant) the Curecanti National Recreation Area Boundary Establishment Act.

If passed into law, CORE would protect and provide more lands for outdoor recreation, and reserve areas utilized for hunting and ranching as off-limits to new oil and gas development.

“For all 10 years I have served as a commissioner, these public lands designations and conservation efforts have been front and center and the CORE Act has been the mechanism to move four individual public lands bills forward,” says Gunnison County Commissioner Jonathan Houck.

“While we celebrate the much-deserved Camp Hale designation and the movement on the Thompson Divide Withdrawal and Protection Act, we will continue to be relentless in our pursuit of making those mineral withdrawals permanent and to have the Curecanti National Recreation Area Boundary Act passed in its entirety,” Houck explains.

Nania also views the CORE Act as a major part of the Red Lady puzzle, which involves protecting water from the Slate River and Carbon Creek from contamination, safeguarding the ore body on Mt. Emmons, and extinguishing mining claims on surrounding lands.

With Red Lady as the iconic figurehead, the Thompson Divide Withdrawal will protect a large footprint of land around Carbon Creek and Whetstone Ridge, where companies have previously staked mining claims. The move will safeguard the area’s critical headwaters region, protecting the health of downstream water users.

Should Freeport McMoRan agree to take on the responsibility and liability for the plant, they will have a perpetual obligation to maintain and operate the plant in exchange for more streamlined processes (i.e., not needing to go through as many steps through the National Environmental Policy Act, despite still being subject to the Clean Water Act and other legislation).

A model for conservation

It has been easy to accuse Crested Butte locals in the fight for Red Lady as being solely concerned with the place they have the privilege to call home. Indeed, Aspen-based journalist Paul Anderson stated, “Once the values of the town were clearly defined and personally imbued, most of the townspeople vowed not to allow our coveted backyard to become a sacrifice zone. In this, we became unrepentant and unapologetic NIMBYs who would hold back the barbarians at the gates.”

Acknowledging this critique, HCCA actively works to combat NIMBY-ism, and is concerned with exporting high standards for the mining industry. As molybdenum continues to be mined for use in everyday consumer products like electronics and mountain bikes, HCCA and other organizations are advocating for better environmental and social best management practices — sharing strategies as they work alongside communities engaged in similar fights.

Additionally, Nania stresses the importance recognizing traditional land rights and utilizing uniform standards of community consent, so that protecting a mountain and a town in Colorado won’t lead harms to befall others in a different part of the west, or the world.

With nearly 50 years of experience serving as an advocate and watchdog, HCCA exports its expertise and serves as a plaintiff in other communities, dispelling concerns that similar issues would be ignored if not staring Crested Butte — and its wealthy, educated populace — in the face.

Nania says that developing good case studies in communities like Crested Butte, which boasts large public support and capacity, does a great deal to establish precedent for related, difficult-to-tackle legal cases.

Legal and social precedents for creative solutions like those finally found in Crested Butte are crucial for supporting communities with fewer resources and less available support. A pertinent example is that of the Apache, currently engaged in a fight to protect the sacred Oak Flat site from copper mining. Water is key there too, with the proposed mine set to remove “about 250 billion gallons of groundwater”

Exporting their conservation success story beyond Crested Butte is part of why Julie Nania and others involved in High Country Conservation Advocates are not, and never will be finished, even if Mt. Emmons receives the perpetual protection that activists have fought to attain for nearly half a century.

And while the fight for Red Lady is what prompted HCCA’s founding, it led to the nonprofit’s involvement in other local concerns surrounding water, timber, and serving as a stakeholder in the GMUG forest planning process.

The group has also become heavily involved in stewardship, with on-the-ground restoration and volunteer projects, stewardship hikes, and other events taking place on public lands across the valley.

Celebrating success

Nania is excited to see what comes next for the organization, and to use the creative solutions found here to support conservation efforts across the West.

And while there’s a lot of work still to come, HCCA will do what it’s done best: Bringing the community together, raising awareness, and throwing “one hell of a party” to celebrate the wins when they do come.

If you want to join that party too, check out HCCA’s 46th Annual Red Lady Salvation Ball, held on August 6 at The Slogar, featuring the Mile High Soul Club. Come out and “celebrate the beginning of the end of the fight to keep Red Lady mine-free!”