By Kira Cordova

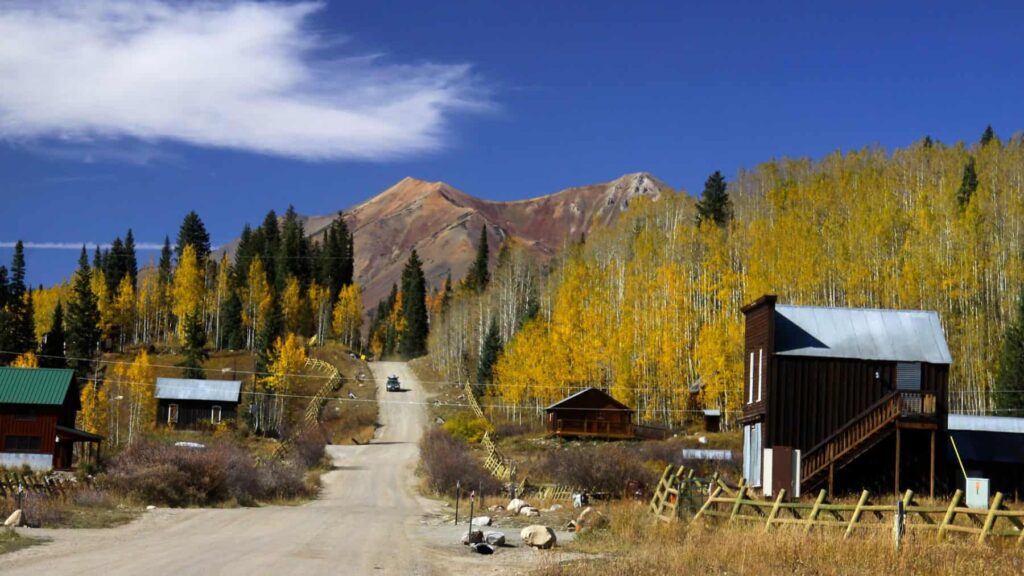

The Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory (RMBL) in Gothic, CO sustains long-term data collection and scientific study with the help of student researchers, providing critical insight into the effects of climate change on the Gunnison Valley — and beyond.

“It’s definitely life changing,” says Western alumnus and returning research assistant David Hopp about his experience with the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory up in Gothic, Colorado. “I was told that before and didn’t truly understand it until [later].”

Hopp had previously participated in RMBL’s undergraduate student science program, where students complete 10 weeks of in-depth, field-based research under the supervision of renowned biologists.

Western biology professor Dr. John Johnson founded RMBL back in 1928, beginning a storied relationship with Western. In the near century since, RMBL has earned a reputation for recording long-term data on the Gunnison Valley’s ecosystems and inhabitants, which offers important insights into the ecological impacts of climate change.

Student researchers play a key role in sustaining the laboratory’s work, gathering data in the field and conducting their own personalized research projects. For their efforts, student scientists can earn academic credits, a wealth of experience, and even free housing, as well as the opportunity for invaluable networking that can launch their careers in science.

“Even if you have 20 students [up there] during the summer, they all contribute to the long-term data [collection] at RMBL,” emphasizes Alyssa Rawinski, a 2023 Western graduate in Biology and the outgoing president of Western’s campus chapter of The Wildlife Society.

Rawinski completed an undergraduate student science project on burying beetles at RMBL in Summer 2022, part of her broader work on a small team of student scientists investigating various research questions about the beetles.

Hopp, who graduated from Western in Spring 2023 with a double major in Biochemistry and Ecology, has seen this cycle in action; this summer will be his third spent up at RMBL.

In his first year up in Gothic, Hopp designed and implemented an undergraduate student science project on the smell profile of the Skyrocket flower for his senior thesis in 2021.

He returned the next year as a research assistant to Professor Diane Campbell of the University of California–Irvine, who oversaw the skyrocket research. This summer, he’s reprising that role.

The long haul: Understanding the ecological impacts of climate change

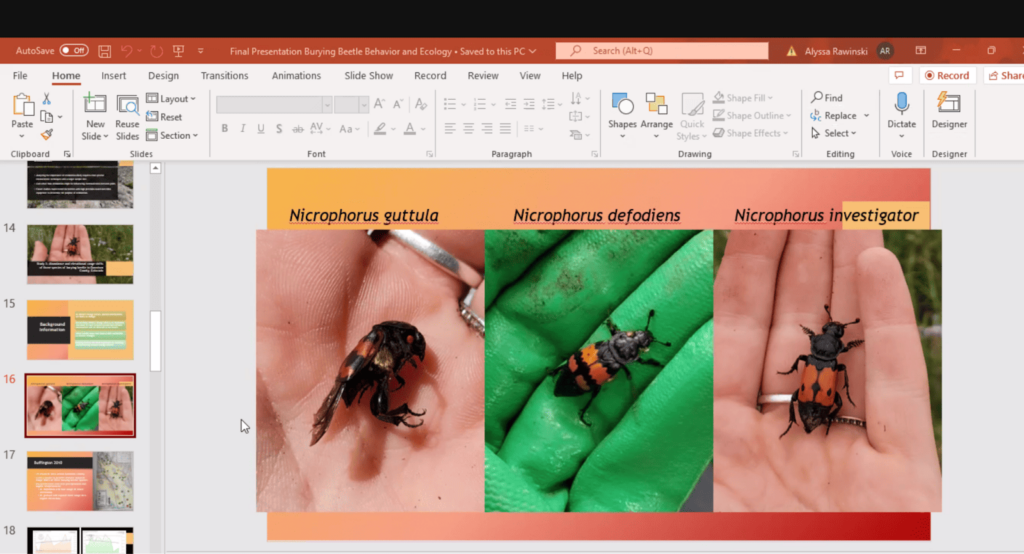

In the summer of 2021, Rawinski studied three species of burying beetles that feed on carrion — dead animals.

She says the beetles are unique because both parents care for their offspring, known in the world of ecology as “biparental care.”

They find a small carcass, usually that of a mouse, roll it into a ball, and lay their eggs near the buried carcasses so their offspring will have a hearty meal waiting for them when they hatch.

The first part of her study covered the effects of stridulation (noises insects make with their wings) on their reproductive habits. The second portion of the study investigated their range in the environment.

To study the effects of stridulation on beetle reproduction, Rawinski clipped a part of a group of beetles’ outer wings, preventing them from stridulating.

She then set pairs on mouse carcasses and observed the speed at which they went through their reproductive cycle, later measuring the size of their offspring. She repeated the same process with a control group whose wings she didn’t clip and compared the results.

Ultimately, Rawinski didn’t find significant differences between the control group and the group with clipped wings. If she were to repeat the experiment, she’d like to expand the sample size and take more precise measurements of the baby beetles to see if their parents’ musical ability affects them in other ways.

The second part of her study investigated their range shift (changes in where the beetles live). In 2009, a master’s student in a summer science program at RMBL named Kevin Buffington explored the abundance of different species of burying beetles at 29 sites in the Gunnison Valley, from Almont to Gothic.

Each of the three different species have different climate and temperature preferences, and Rawinski suspected that, in the 12 years since Buffington’s project, climate change and warming had affected where each of the species carves out a home in the valley.

Buffington’s study utilized niche modeling (which uses computer algorithms and environmental data to estimate where different species will live in the future) to predict how their ranges might have shifted. Rawinski returned to 10 of his sites and repeated his population measurements to see how they’d changed —and if his models had proven correct.

“They were pretty much spot on,” she says of Buffington’s predictions. “He predicted that the more arid species (Nicrophorus guttula, the species that prefers the desert) that lives in the sagebrush would move northward — higher in elevation,” she adds.

In fact, all three of the species that Buffington tracked showed a range shift northward and higher in elevation as climate change caused habitats at lower elevations to become warmer and drier.

For Nicrophorus guttula, this phenomenon expanded their range. But for Nicrophorus defodiens, the least common species of burying beetle —and the one most fond of moisture — changing climatic conditions led to a significant range loss, which will likely continue as the American West only gets drier on average.

Rawinski says that the findings of this part of her study were twofold. “Niche models can be incredibly accurate” she notes, which leads to her second conclusion: “In [just over] 10 short years, we can see the effects that climate change is having on these species.”

Mentoring the scientists of tomorrow

While RMBL student scientists continue tracking the effects of climate change on local ecology, resident research mentors (professors from universities across the country) share a wealth of knowledge and research spanning decades.

David Hopp’s research mentor during his REU summer, Diane Campbell (a professor at the University of California–Irvine), is just one example.

“She’s been going up there since the mid 80s,” Hopp says of Campbell, whose experience over more than 40 years at Gothic give her an invaluable vantage on climate research.

Hopp says her work and the student science projects she advises are “hyper-focused” on one species: the skyrocket flower, which Campbell is an expert in.

The resilient species extends across a variety of ecosystems, from coniferous forests to sagebrush plains and high mountain slopes. The data gathered up in Gothic is just one square in a quilt of data from across the Western United State.

“We’re interested in every aspect of the flower,” Hopp expands, including its pollinators and the herbivores who eat it (like elk and mule deer), as well as its size, color, and even smell, elements which paint a complete portrait of the flower and how it’s affected by an issue as complex as climate change.

Hopp’s research focuses on the smell the flower produces, which he says is “a really nice combination” of his majors in chemistry and ecology.

“Every summer, we stress out the plants in different ways and see what happens,” he says about his and Prof. Campbell’s research.

Their ultimate aim is “simulated climate change,” so during his first summer, they put individual skyrocket plants in mini-greenhouses to see how they’d react.

“The things that we found are difficult to interpret,” says Hopp, adding, “it’s cool to see these responses and not understand them — it’s okay to not know things.”

For instance, higher temperatures made the flowers grow longer and produce more nectar, an attractive characteristic for pollinators, and a phenomenon to keep an eye on as the climate continues to change.

The impact of student research

While Hopp and Campbell are still trying to understand what’s happening with the plants they exposed to increased heat these past few summers, Hopp will also be working on a specific, as-of-yet undecided research project concerning the skyrocket.

They’re also working on combating the lack of literature available on the flower’s smell.

“We’re actually writing a paper now on that first summer that I’m going to be a coauthor on,” he says excitedly. They hope to publish the paper, which will present possible explanations for the changes they observed in the plants when exposed to higher temperatures, in July.

Both Rawinski and Hopp emphasize that student science can be just as impactful as research completed by people who already have their degrees.

“[Student scientists] are scientists doing important research,” Rawinski affirms.

In addition to the insight their projects offer into climate change, student scientists of all ages at RMBL receive training and permission to conduct hands-on projects with wildlife, providing valuable data to help understand the high-alpine ecosystem.

In that vein, Hopp says one of his undergrad colleagues from past summers at RMBL — who studies at Harvard University — will be conducting a study on hummingbirds’ taste preferences for his senior thesis, which will likely include catching and training hummingbirds.

The nitty-gritty of RMBL life

The undergraduate experience at RMBL take two forms, with both paths leading to 10 university credits issued either by RMBL or Western. Depending on their preference, accepted students can choose to conduct a full-time independent research project, or an independent research project paired with a short RMBL course.

The latter path is generally recommended for students without research experience and students especially interested in the course offerings, which vary from year to year. This summer, the courses offered are Rocky Mountain Ecosystems and Wildlife Biology.

All undergrad student science programs are 10 weeks long, and there can be up to 40 undergrad students in every cohort.

For 10 of the 40 undergraduates, student science at RMBL is conducted through the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program, which covers the full cost of the student science program (including the cost of the credits earned) and supplies a $5750 stipend and $400 towards travel costs.

“The scientists up there, [both]the professors and the students, come from all over,” says Rawinski. Her 40-person cohort includes six Western students.

Every year, RMBL produces a guide to the professional resident research mentors and the projects they’ll be supporting student scientists to conduct over the summer. RMBL then matches admitted students with mentors and their associated projects based on availability and preference.

Rawinski says that she filled out a survey about which advisory and projects she was most interested in shortly after she was accepted. She selected her top five researchers and ultimately ended up working with the advisor she had ranked second.

When asked about the most significant challenge of the program, Rawinski says it’s the stress of trying to complete a complex research project in just 10 short weeks.

“They did have benchmarks, some points along the process,” she qualifies, but adds, “It does take a lot of self-dedication and motivation.”

Despite the fast pace and the gravity of their work, it’s not all serious business in Gothic.

“They also had some fun stuff planned for us,” says Rawinski.

In addition to professional development like seminars on public speaking and professional writing, RMBL staff planned hikes for the undergraduates over the summer, and even hosted a cabin crawl, when student scientists and staff who didn’t live in the cabins got to tour the on-site housing and socialize.

Hopp says the key to making the most of a summer up at RMBL is being open to new experiences.

“A lot of people who come here that are not from this area, they have no idea what it’s like to live in a town with no sewer,” he laughs. “It really puts people outside of their comfort zone … I’ve seen people lean into that and change their life in Gothic.”

The student application process

Students interested in joining RMBL’s undergrad program can apply online. Prospective students who complete their applications before Feb. 15 the spring prior to the summer science program don’t have to pay the $40 application fee (for students interested in the 2024 summer season, that means applying before February 15th, 2024). The 2024 application is not yet available but will open in the fall.

All applicants, regardless of when they apply, must submit a completed essay, two recommendations, an unofficial transcript, and a financial aid form.

Rawinski says she applied the fall before her research term. Once she was selected, she attended Zoom meetings to be matched with her advisor and meet her group members — the other student scientists working with her and her advisor.

There is limited on-site housing in cabins at RMBL in Gothic, and whether or not undergrads will live there is determined on an individual basis.

“If you don’t get on-site housing, you have to find your own in Crested Butte or Gunnison,” Rawinski explains.

Hopp adds that the experience for each student, and the total cost of the program, will likely vary based on a variety of individual factors.

Depending on a student’s financial aid application and whether or not they’re REU recipients, RMBL or the National Science Foundation may cover the cost of housing for participants, either in the form of on-site housing in Gothic or by covering the cost of rent in Gunnison or Crested Butte for the summer.

Without financial aid, the cost of the program (including room, board, and the cost of college credits issued by RMBL) is $8,500. All non-REU applicants are automatically considered for RMBL financial aid based on their applications.

Hopp, in his role as a returning research assistant, is a direct employee of UC-Irvine, which covers his housing in the valley.

Returning as a research assistant

“Ask and you shall receive,” says Hopp about undergrad student scientists who want to return to Gothic as research assistants. “There’s so many groups up there that need help, and especially if you already have experience,” he expands.

He describes his role as an “extra pair of hands,” and says he also assists Campbell’s undergraduate student scientists in designing their research projects.

Hopp appreciates the expanded networking possibilities as a research assistant.

“I felt like I was a lot more connected to the older people,” he says about last summer. “When I was an undergraduate, I was stuck in the group of undergraduates. As an actual employee, I was hanging out with the kitchen crew, the work crew, [and] the other research students.”

He recommends following that path and reaching out to a research mentor directly, although there are limited opportunities to work directly for RMBL as a research assistant.

What’s next for Hopp and Rawinski?

Rawinski graduated from Western this May and plans on staying in the Gunnison Valley to work as a biology technician for the U.S. Forest Service.

After completing his first summer as a research assistant at RMBL last year, Hopp traveled around South America before returning to Colorado to be a research assistant once again this summer.

“I’m thinking this will be my last season in Gothic,” he admits. In the future, he sees himself earning a PhD. “I know that, at some point in my life, I’ll go back to school,” he expands, “I’d love to be a professor and do research [professionally].”

Both say their experiences at RMBL have connected them with people they’ll stay in contact with for a long time.

“The community is so amazing,” explains Rawinski. “It’s a great place for networking.”

Speaking about the professionals he’s met, Hopp sums it up: “I’ll be speaking with them for my whole career.”