By Courtney King

Courtney King is a 2021 graduate of the Master’s of Science (MS) in Ecology program at Western. Below is her guest essay recounting her experiences on the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT).

Two days after graduating from Western, preceded by weeks of worry, months of planning, and years of dreaming, I arrived at the Southern Terminus of the Pacific Crest Trail. The night before, I had packed and repacked, discovered firsthand how heavy water can be, and shared my most pressing fears about the trail with a close friend who was sending me off.

I was about to take the first steps of a months-long journey that, while I didn’t want to be presumptuous, I knew I could complete. Years earlier, I had been encouraged by a friend who had completed the Appalachian Trail, and his advice on the importance of preparing emotionally and mentally. By that point, I had viewed countless photos of fellow hikers beginning (or for the smaller proportion hiking North-to-South, ending) their hikes at the stone monument marking that end of the trail.

All the pictures I had seen, however, obscured the glaring fence along the Mexican border, over 20 feet tall and stretching off toward the horizon. The fence, followed by scraps of fabric left on the desert floor and signs encouraging anyone traveling through to turn back, were stark reminders that others had been driven to travel through the Sonoran Desert to preserve their and their families’ lives.

I, on the other hand, was hiking across the desert for…fun? Well, I still wasn’t sure exactly why I had set out on the trail; although I had thought of some responses to provide when questioned, they all came after the fact. My backpacking experience, too, came after I had already decided I would hike the PCT. I was technically able to say that I had some skills under my hip belt, as I had done a couple weekend trips the summer before, but knew I was really a beginner.

Could less than 50 miles and a handful of nights spent in a tent really prepare me for a months-long, 2,650 mile hike from Mexico to Canada? These worries and others, from the life-threatening (did I start too late to beat the summer heat) to the shallow (would I meet a trail family or end up with a unique trail name), and all potentially hike-ending, swirled in my head as I said goodbye to my friend and “real life”.

It should come to no surprise that my first days in the desert were hot. What worried me, however, was how intense the sun felt on my back when I knew it had barely reached 85 degrees Fahrenheit. If it felt this difficult now, how much worse would it feel when temperatures were 15 or even 25 degrees higher?

My first day, I kept passing other hikers finding respite in the shade for a few minutes, before stopping to do the same myself. It took me a few days, days which unfortunately seemed to have caused pain in my left shoulder blade that never fully went away throughout my hike, to realize that much of my issue was that I was carrying a few too many liters of water with more weight on one side of my pack.

Fortunately, as the days passed, I met and became fast friends with fellow hikers who either had more experience or were quickly figuring it out themselves. Many say that hikers “pack their fears,” and it was indeed a challenge to not fill up multiple liters from every water source, but I started to take the advice that, “water is for drinking, not for carrying.”

As time went on, I also became stronger, beginning to build up my “hiker legs”. I was grateful for how well my body was holding up after a string of 20-mile days, and didn’t take a true “zero” or no-mile day until I was a month in. Around that point, something changed. I know longer felt like I was simply on a long series of day hikes.

Along the trail, I faced decisions from where to camp to whether to hike through a potentially sketchy section of trail where a rockslide had occurred the year before. From the second experience I learned news could travel and be inflated along the trail like an extended telephone game; as I had been told by two women in their 80’s hiking the opposite direction, doing a tiny bit of rock scrambling turned out to be no big deal. At the same time, I was glad to hone my ability to decipher overstated concerns from real dangers.

After putting in hundreds of miles, meeting the unique inhabitants of Southern California (plants, wildlife, and people), receiving the “trail name” Cinderella after almost losing a shoe, and more, I finally felt like a thru-hiker. This feeling carried me to Kennedy Meadows, a place that serves as a milestone to PCT hikers as the “Gateway to the Sierras”. While I had loved my time in the desert, finding it to have more biological and geological diversity than I previously imagined, I could not wait to arrive in the Sierra Nevada.

My brief time in the Sierras felt like a whirlwind, with every day of the ~400 mile section full of difficult climbs up high-elevation passes, magnificent views of mountains and meadows, and icy blue lakes that many challenged themselves to plunge into. Just as I felt immersed in scenic beauty, I finally felt immersed in the broader trail community, having found a group of close friends (my “trail family”) and an extended “bubble” of fellow hikers. This extended group lived by the famous African proverb, “If you walk alone you’ll go fast, but if you walk together you’ll go far.”

I felt a sense of kinship with those who, despite some of us having just met, set our alarms to wake up at midnight for a sunrise summit of Mt. Whitney, or Tumanguya as it is known in Pauite. I thought often of the parts of nature I hold dear, realizing that while I had never been to this place before, I felt a sense of loss for the little snow that had fallen. In June, there should have been some patches of snow remaining, but this year it was long gone. The serenity of the Sierras was not fully extinguished, but certainly disrupted by news of what we had known would come at some point: wildfires.

Transitioning out of the Sierra Nevada, news from ahead and smoke in the distance served as constant reminders that we were heading towards the now-infamous Dixie Fire. Indeed, stopping to check my phone for the first time in days, I learned that a road I had originally planned to exit from was closed as towns had begun to evacuate. Fortunate to have internet access, which helped my hiking partner and I evaluate backup plans, I eventually hitched rides and met up with friends who had been escorted off the same, now-closed road.

We lamented the section of trail, including the halfway monument, that we would miss. The next couple weeks seemed to continue the same way: we would make a plan and get comfortable with it, only to hear news about a new spot fire ahead that would completely rearrange our plans, and start all over again.

If there could be a silver lining to this time, avoiding fires and smoke ultimately brought my extended group of friends on the trail together, physically and emotionally. Those who were not yet far enough ahead of the Dixie Fire either had to find highways on which to walk around the fire, becoming an increasingly long and difficult prospect, or to hitch a ride. Myself and about a dozen other hikers, getting off trail in different areas as they were being evacuated, ultimately reconvened by chance in the town of Fall River, CA.

We had found immense support in the communities surrounding the trail and would continue to do so, this time in the form of a woman in a pickup truck offering to drop our packs at a church in the town of Burney Falls that allowed hikers respite in their gymnasium. The following day, as more from along the trail arrived seeking comfort and companionship, we held a “Hiker Prom.” The night served as both a reunion and a temporary goodbye, as some continued on the trail from Burney Falls the next day, while others sought out rides even further north where they hoped they could avoid the fire’s spread.

Eventually, under smokey skies, I crossed with friends from California into Oregon. The trail looked the same, and the air quality index was still too high for comfort, but I was finally in a new state after three months. Plus, I knew that Oregon had notoriously “easy” terrain, with some challenging themselves to hike through the entire state in less than two weeks. I enjoyed stopping at the many lakes the trail passes by, most of which have resorts with warm food (a luxury after weeks of cold ramen), and took a detour around the rim of Crater Lake.

After getting another ride around a closed section of trail, I spent a night near the eerie Mt. Hood, experienced the stunning Three Sisters Wilderness for the first time, and tried not to fall while hobbling across painful pumice stones. Suddenly, Oregon was falling behind me, and I crossed over the Bridge of the Gods into Washington.

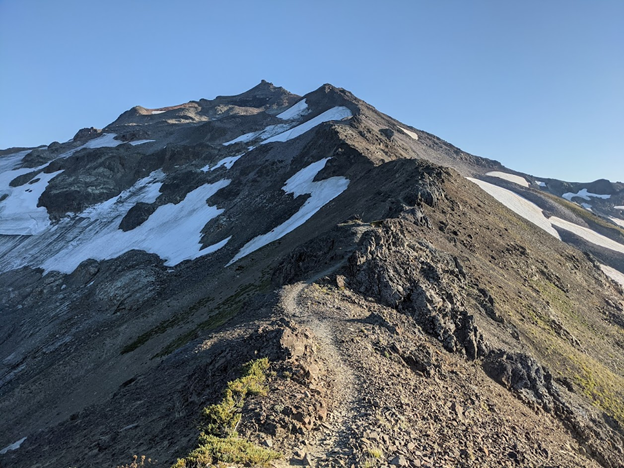

Washington was, as I had imagined and hoped, wondrous. I revisited wildlife I had first encountered in Colorado, from elk crashing through trees to pikas squeaking in the scree. The relative calm and quiet at this point in the trail (many hikers had already finished or left early), combined with the expansive views of the Cascades, gave me the space to reflect upon my journey and what was ahead.

I experienced what felt like some of my most difficult times on trail, with sleepless nights, days of freezing rain, and intense river crossings. I was asked what had been my scariest moment on the trail, and thought of these moments; that is, before remembering that I had different fears in the preceding weeks and months, I had just forgotten them as my skills grew and the environment around me changed.

I also couldn’t pinpoint my favorite moment or section of trail, enamored with all that I had experienced so far. Each moment of the trail had brought me gifts, at times tangible (the Pacific Northwest’s provisions of wild huckleberries and blueberries were a treat), but often less so.

On September 22, after over four months of hiking, I reached the Northern Terminus of the PCT. I felt a strange sense of finality; after reaching the end of a pivotal moment in my life, I was left with more questions than answers, all of which could be summarized as, “What now?” The trail had become my home and entire life, and returning back to “normal” in the following weeks felt anything but.

I had prepared for the possibility of post-trail depression, and found support in friends similarly struggling to re-integrate, but that didn’t make it any easier to recount my experiences. It was particularly difficult to express my frustration over having to bypass so many miles of the trail. I still felt accomplished, but couldn’t say I had successfully completed a continuous thru-hike.

While I was fine with that, others off-trail didn’t “get it”, and thought I simply needed more comforting words and encouragement.

As I spent the time to rest, recover, and address my complicated emotions surrounding the trail, I found it easier to speak about. I had grown and changed in a short amount of time, and while I frequently meditated on my hike of the PCT, I also knew it was time to move on. In the last few weeks of my hike, I thought often of a sentiment I had been told in Southern Oregon: “You never get off trail, you simply move on to a new one.” Although this adventure left much unanswered, it provided me a few immensely important certainties.

I had found camaraderie in a community with a unique language and lifestyle, whose members may be fluid, but who I hope to keep re-finding throughout my life. I felt sure in my choice of a career, to have dedicated my life to preserve the ecological communities I lived within and whose natural cycles I saw disrupted.

I knew I was strong and adaptable, could rely on myself to weather the storms that faced me, but could also humbly accept the favors I was generously offered. Navigating without set waypoints, I had little idea where I would end up or what I might do, but would surely bring with me the memories from my first long trail and yearning for more.