Master’s of Environmental Management (MEM) student Anna Markey uses trail cameras on Coldharbour Institute property to study ungulate behavior with the aim to reduce costly wildlife-vehicle collisions

This story is part of an ongoing series highlighting Clark Family School of Environment and Sustainability (ENVS) projects and their relations to the broader environmental movement and to the Gunnison Valley community.

As part of the Master’s in Environmental Management (MEM) program, students must complete 600-hour projects in collaboration with sponsoring organizations, which can be nonprofits, government entities, or private individuals or companies. Coming into the program in the summer of 2020, now second year MEM student Anna Markey was on the lookout for a project which furthered her already extensive background in wildlife biology and research.

Previously, Markey worked on projects collaring cougars in the Gila National Forest in New Mexico and the Manti La Sal National Forest in Utah. She also had the opportunity to monitor, collar, and care for endangered species including cheetahs, leopards, and black rhinos in South Africa. While working in Florida, she assisted in an ongoing deer collaring project and in collaring the elusive Florida panther.

In Colorado, Markey has continued working with wildlife by assisting the Bureau of Land Management with snowshoe hare surveys in the Powderhorn Wilderness, leading both the ungulate survival project, and the migration corridor projects examining the behavior of deer and elk in the valley. Recently, she has been assisting the Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) mountain lion collaring project.

The project’s genesis

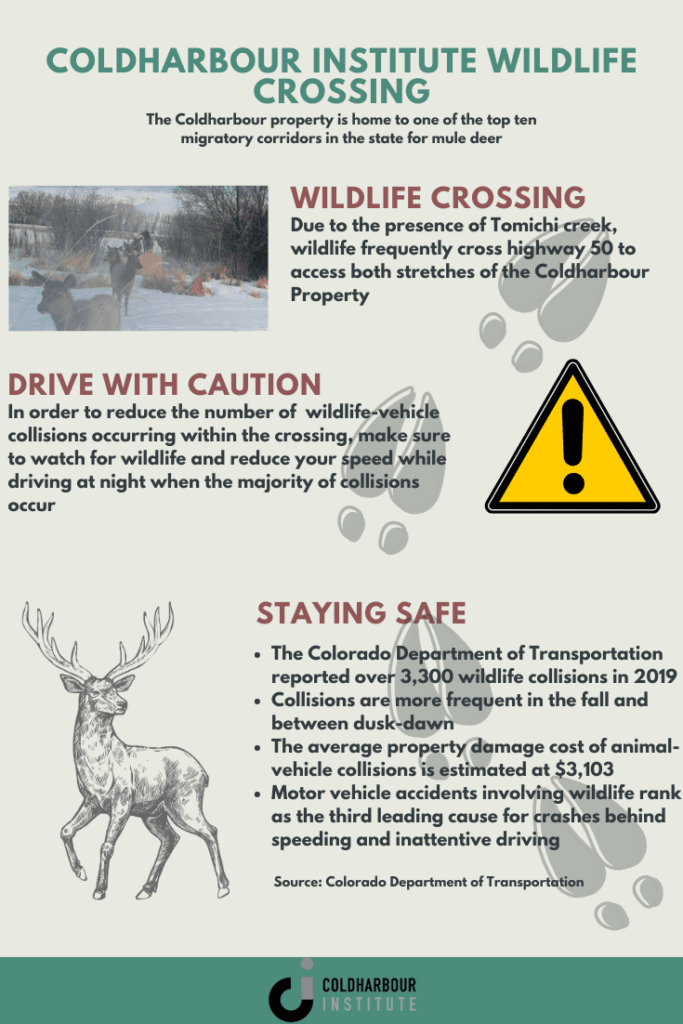

In early fall of 2020 during a required five-week course examining the role of science in environmental management, Markey homed in on an opportunity for a fitting wildlife master’s project. The project, pitched to students by Coldharbour Institute director MJ Pickett, stemmed from a high number of wildlife-vehicle collisions on Highway 50 along the Coldharbour property.

The original scope of the class project was to investigate the possibility of installing highway signage to warn motorists of wildlife hazards, as well as to consider using other forms of public communication. That project resulted in the publication of a blog post, a series of bumper stickers, and a poster with informational messaging.

Markey, already a Coldharbour Institute Fellow and actively in search of a master’s project, decided to continue the class project, undertaking a graduate research project to study the movement of ungulates (deer and elk) along Highway 50 near Coldharbour.

In May 2021, Markey installed 24 trail cameras (18 of which came from a donation from the Center for Public Lands) spanning the length of Coldharbour’s property along the north and south sides of Highway 50. The cameras are stationed between 120 to 150 yards apart, with the goal to capture ridges and valleys where deer and elk may congregate.

“Deer are particularly inclined to seek out the easiest options for movement. This tends to be in valleys and ravines or saddles between ridges and mountains. This allows for less energy exertion and foliage tends to grow better in lower areas because water will collect there,” Markey says.

The cameras are checked once a month and aim to identify the density and movement patterns of deer populations. Once analyzed, the photos can assist in identifying problem areas with particularly high ungulate traffic near roads, the most active times of day, and other factors that contribute to wildlife-vehicle collisions.

Markey’s overarching goal is to educate motorists about the inherent risk of driving in areas rich with wildlife species and inform them of times of day when they need to be most alert.

Danger for motorists is highest predominantly during transitional times, at dawn and dusk, and at the turning of the seasons: spring to summer and fall to winter. [When] we have snow, sometimes it can get harder for ungulates to get back off the road if snowplows come through,” notes Markey.

Markey says she typically has about 40 to 50 photos per camera per month (but when cows were out grazing on the property, she tagged around 8,000 photos in one month). Magpies, notoriously clever birds, have proven to be an enemy of science, taking down cameras in a fit of curiosity. Once, an emboldened elk even got in on the camera-busting frenzy.

Another, more pedestrian obstacle for Markey’s research is identifying herds of elk or deer when only one or two appear on camera at a time. High animal densities are a major contributing factor in vehicle collision risk and a key research question for Markey in her analysis.

Difficulties aside, analyzing the photos is Markey’s favorite part of the process, with little telling what she may discover. Although exciting, it can be a long process. After pulling the SD cards from the 24 cameras, Markey spends an entire day processing and tagging photos. She also documents species, individual count, time and date, and weather conditions. She estimates she has spent more than 600 hours on photo analysis alone.

Rendering the project even more important are rumblings that Highway 50 east of Gunnison may be in line for expansion from two to four lanes. The expansion would almost certainly increase risk of collisions with local wildlife populations. Markey’s hope is that her study could contribute to securing and successfully siting a wildlife overpass (or perhaps an underpass) should the highway expansion plans come to fruition.

Along with data that will be used to try reducing costly collisions, other information has been gained from the study. “There’s a greater species richness than I expected on the Coldharbour property, which is really cool to find,” says Markey, who has spotted black bears, bobcats, coyotes, deer, elk, skunks, badgers, porcupine, and other animals on her trail cameras.

After taking down the cameras in late March 2021, Markey’s project will culminate in May with a final report analyzing ungulate density and a map outlining hot spots of potential concern. “I’d like to see it inform management decisions in the valley whether that be in the form of knowledge about migration patterns, records of certain species of wildlife in general, or even decisions about future hunting tag numbers,” says Markey.

Post-graduation, Markey’s goal is to continue working as a wildlife biologist in the field, ideally with a state or federal agency where she can continue her passion: collaring animals to assist with management decisions.

Editor’s note: Stay tuned for more ENVS Project Series features!