The increasingly popular 3+2 programs produce short term value for universities and students, but fall short under scrutiny on both rigor and long-term benefit.

Increasingly, colleges and universities, from the inexpensive, high-value community college to four-year public and private universities, are innovating their academic programming and delivery models as fewer students are applying to, and attending, college.

This trend has taken multiple forms, including the increasing online and part-time degree options offered by many institutions, expanded graduate offerings, and more recently—the proliferation of 3+2 programs, which allow students to complete a master’s degree on an accelerated five-year timetable.

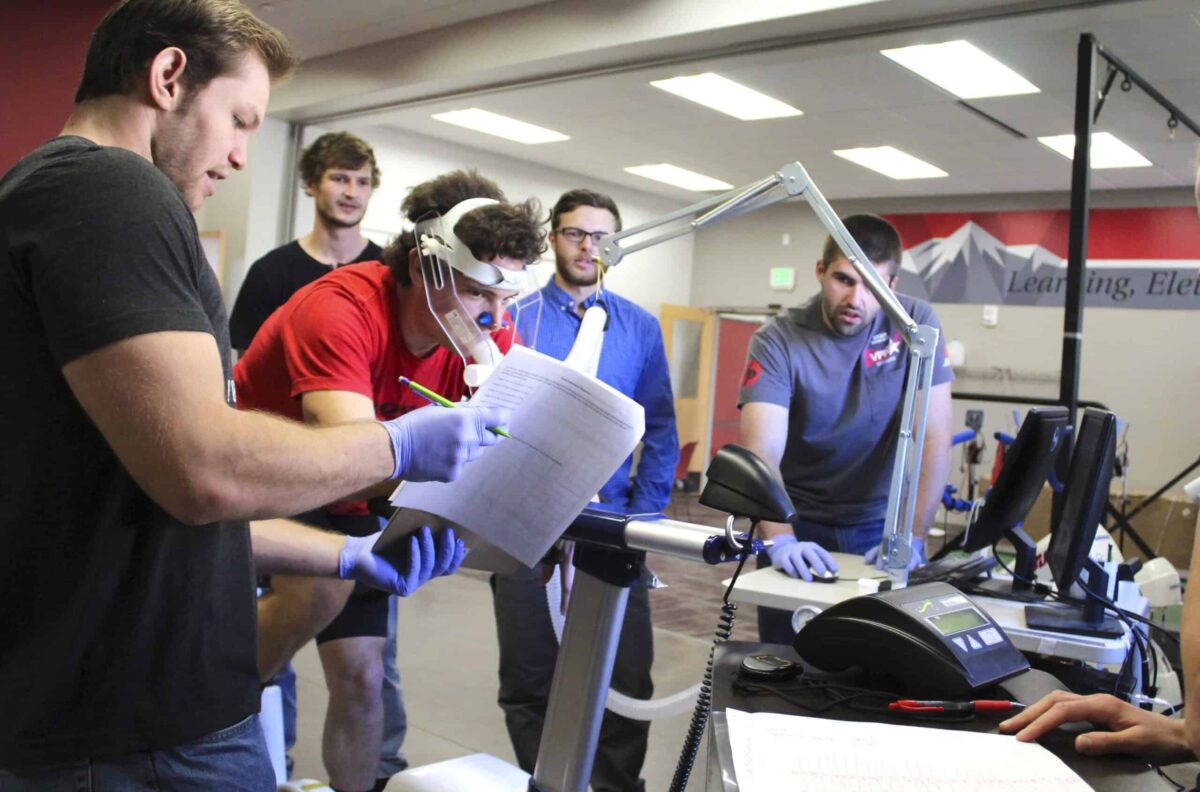

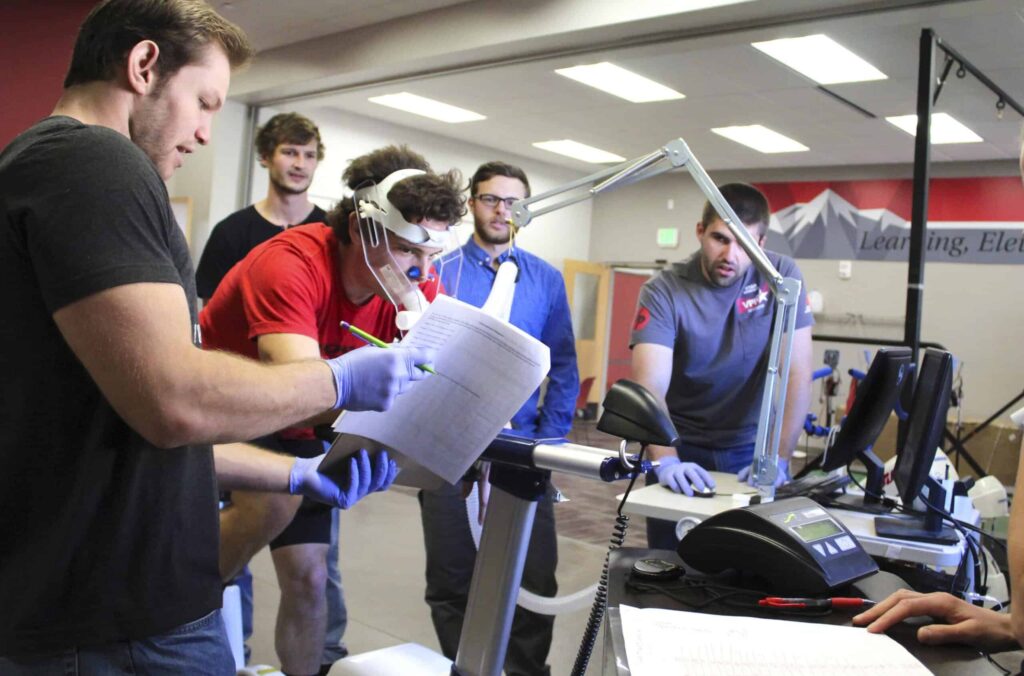

Currently, Western has nine such programs on offer, in fields that include rural health, environmental management, ecology, high altitude physiology, education, museum management, and creative writing.

It is easy to see why these programs are enticing for both students and schools. For students, the program allows them to shave a year off of their schooling—pocketing the tuition and fees they otherwise would have paid out, and “saving” a precious year of their time.

For colleges, the programs attract high-achieving students, nets another year of tuition. This is particularly important for graduate offerings, which are cash-funded at Western—meaning they must pay for their program’s costs out of student’s tuition dollars.

So, what’s the problem?

Well, 3+2 programs are so inherently focused on cramming in material and sticking to the schedule that they can fall short in other important areas. To pick some low-hanging fruit: Four years of attending school is a long time, and 3+2 students will almost undoubtedly experience a greater level of academic fatigue than their peers who enjoyed a break, even if it was just a full summer off after graduating with their bachelor’s degree.

When the 3+2ers finally arrive in the all-important fifth year, where they are completing their graduate projects and thesis, and presenting, or in some cases—defending their work, they are often limping to the finish line. And who can blame them?

These students likely would have been better served in many cases by some time off to recuperate from academic reading, writing, and the stress of collegiate life, which often extends into alleged break periods like Thanksgiving, spring break, winter, and summer—particularly in graduate school.

3+2 programs can also reduce academic freedom and the opportunities for exploration throughout college. For students who are eyeing a 3+2 program, they must apply for admission in their junior years, having met a specific set of academic and course requirements (often internship requirements, too) to gain admission to their respective programs.

The strict emphasis on checking off boxes in pursuit of graduate admission may deter them from exploring courses they find interesting, taking a job in a parallel or unrelated field, or pursuing other natural meanderings that could produce fruitful outcomes themselves, or even lead them down a path they ultimately prefer.

Additionally, 3+2 programs rob students of the full graduate experience. It is simply not possible to learn as much as five years as it is in six, and attempting to do so overloads students, and waters down both the final year of their undergraduate education, and the first year of their graduate one—the bedrock of their studies.

This is ultimately unfair to the 3+2 students, who are not getting the highest quality education they could, and to their classmates, who often have to engage in group work with 3+2 students who are overstretched and at the end of their academic wits. From a purely academic perspective, nobody wins.

Students in the 3+2 programs are expected to be exemplary—a cut above. And they often are, do not get me wrong. Yet the institutions admitting them are inherently biased towards offering acceptance to as many students as the program can feasibly allow to garner more tuition dollars.

Doing so puts borderline students in a precarious position of high stress and expectations, which is both unfair to students, and not conducive to learning.

Finally, 3+2 programs do not allow for students to graduate with their undergraduate degree and venture out into the world—getting a seasonal gig, joining AmeriCorps or PeaceCorps, working for a few years, and then returning to graduate school with a clearer picture of their academic and professional intent.

This gap year (or gap years, plural) is often cited as critical to the development of one’s interests, and for good reason. It is often difficult to translate classroom settings into a realistic vision of the working world, or even of many graduate programs.

Thus, the more “real life” experience garnered before taking the leap to graduate school—a difficult, stressful, often expensive undertaking of two or more years—the better in most cases for students to make decisions that will have ramifications on the remainder of their lives.

Traveling, taking a paid internship, volunteering, trying a new entry-level gig, and advancing their education independently during that gap period can make a big difference in a student’s maturity, and in their confidence to pursue a graduate education in a given field of study.

None of this is intended to take away from the accomplishments of those who are eyeing, currently undertaking, or have completed 3+2 programs. From a financial vantage, they are a smart move for those with clear intent on their chosen path.

It is also clear why universities are increasingly churning out 3+2 graduates in an increasingly competitive marketplace for student attendance and tuition. The incentives in play are obvious on both sides.

Yet there are substantive issues at the core of 3+2 programs, as more students opt for that path—the value of a master’s degree, both intrinsically in terms of student effort and learning, and extrinsically within the marketplace for jobs and other positions, is lessened.

How big of an issue that is to you likely depends on your perspective on the issue, but it is certainly a point to consider as Western ramps up its graduate offerings and looks to expand their cohort sizes.

There is no clear answer to this conundrum, and it is likely that universities, including Western, will continue to continue down this road. Accelerated degree programs may sound phenomenal on paper, but they often come up short in practice.

Moving forward, I would urge caution on accelerated degree programs—both for the sake of the student experience, and to preserve the academic integrity of universities.

Ultimately, the responsibility for limiting the size and scope of 3+2 programs must lie with the university—acting on behalf of the student body and considering the long-term impacts for all involved parties.