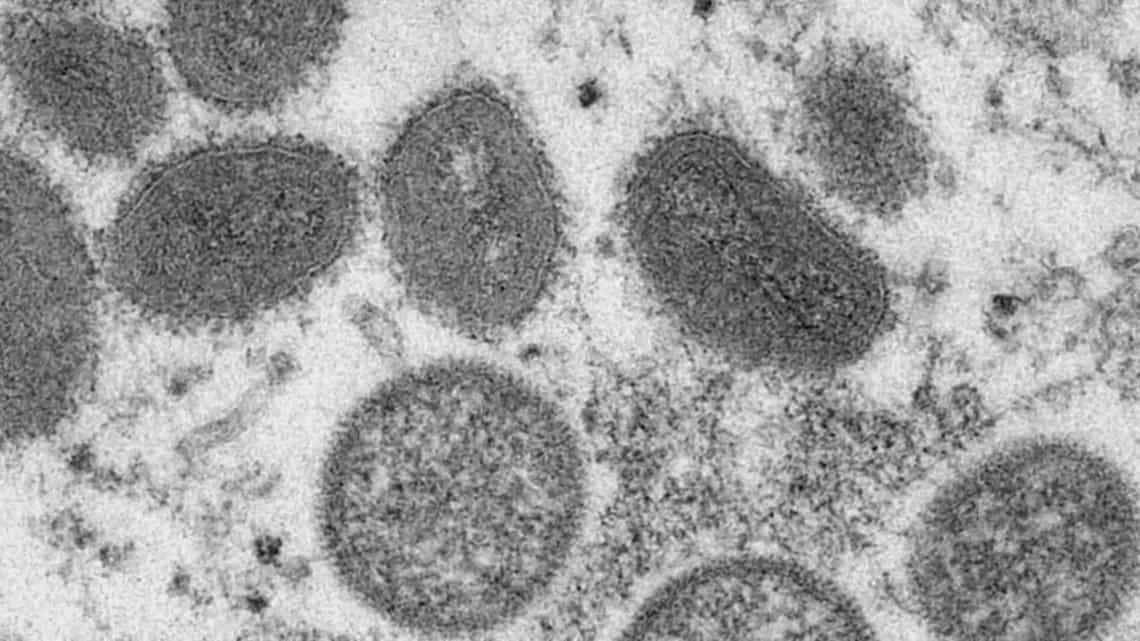

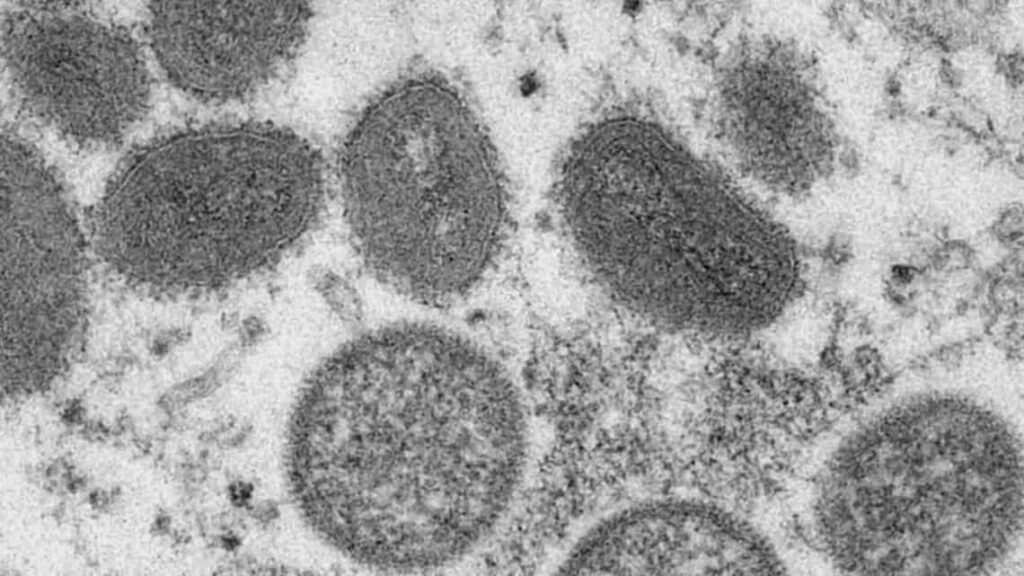

Monkeypox is a disease spread by the monkeypox virus. Initially discovered in primates back in 1968, the disease was first seen in humans in 1970. As an orthopoxvirus, monkeypox is related to smallpox, but is significantly less dangerous to human life in most instances.

Before 2022, the monkeypox virus was known to be present in multiple western and central Africa countries, but a cluster of cases was discovered in the United Kingdom in late April.

Flash forward more than three months, and confirmed cases in the United Kingdom now number more than 2,500. Across the pond, the disease has also taken firm root in the United States — with more than 10,000 confirmed cases across America (the most in the world).

Colorado reported a pair of cases in May, a half dozen in June, 66 in July, and more than 30 thus far in August, according to information provided by the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment (CDPHE).

In just the last week, multiple cases of monkeypox were confirmed in Boulder and La Plata counties. As case numbers continue to climb, the Biden Administration officially declared the virus a public health emergency back on Aug. 4.

The lowdown on monkeypox: Testing and vaccines

Joni Reynolds, Gunnison County’s executive director for Health and Human Services, says that Gunnison now has the ability to test for monkeypox, which involves sampling the rashes and sending the samples off to state labs.

She adds that several tests have been conducted by the county for those who were deemed at risk of viral exposure. All of those tests have come back negative.

Reynolds stresses that individuals who are presenting monkeypox symptoms — as well as individuals who believe they may have been exposed to the virus — should not hesitate to seek county testing.

“Testing supplies are readily available…supplies have not been a challenge,” she adds. People looking to get tested — or with questions regarding a possible exposure, can call the Gunnison County Health and Human Services Department at (970) 641-0209.

Another tool in the toolbox for public health officials looking to slow the spread of monkeypox is the FDA-approved vaccine JYNNEOs, which is being introduced throughout the country in a coordinated effort designed to put the currently limited supply to the most effective use.

While Reynolds says the county has been approved to administer the monkeypox vaccine, Colorado has just about 18,000 total doses in its initial allocation — rolling out several thousand at a time to 10 of Colorado’s more urban counties.

“The state looked both at where at-risk individuals reside — they used a proxy measure using the [number] of individuals that are on PREP, a preventative medication for HIV infection, along with the actual number of cases to determine where those doses would be allocated,” Reynolds says. “Gunnison, along with 54 other rural counties, were not part of their distribution.”

But Reynolds says that Gunnison County has the ability to refer at-risk individuals from the community, and that there’s an online signup form for the vaccine, along with more information, available on CDPHE’s website.

“I think the couple thousand slots fill up pretty quickly, but anyone can sign up for those,” Reynolds adds.

Understanding transmission and symptoms

Regarding the disease’s trasmission, Reynolds stresses that monkeypox is spread through prolonged, close physical contact — largely by sexual activity, but also via mouth-to-mouth exposure (i.e. kissing), and via skin-on-skin contact with rashes.

Early symptomatic indicators of monkeypox include fever and fatigue, which typically develop one to three days before the onset of monkeypox’s telltale sign —: the aforementioned rashes, also known as lesions — which can range in quantity from one or two to several hundred in different individuals.

The development of lesions is the primary sign that an individual has become contagious, but Reynolds notes that it’s possible that someone could transmit monkeypox via mouth-to-mouth contact before the rashes appear.

Reynolds also cautions that the lesions can sometimes be found solely in the genital and rectal region, and could be missed without close inspection.

She adds, “The individual may not be aware, because that might not be an area they can see, or that they check on a daily basis.”

The lesions often occur in five stages: macules — discolored, flat portions of skin lasting up to two days, papules — raised discolorations which can span another two days, then vesicles — which closely resemble blisters, pustules — round, hard, and opaque lesions that appear cloudy and can last as long as a week, and finally scabs — which may last another two weeks as the body heals.

After a person contracts monkeypox, they are predominantly contagious for a period of seven to ten days after the rash’s onset — but may require up to a month to heal fully. After the scabbed lesions have fallen off, an individual is no longer contagious.

“Right now, the recommendation is that individuals isolate until their rash is completely healed, with new skin growing,” clarifies Reynolds. “The [virus] is not known to be contagious that entire time — but there is a small risk, and so the isolation [period] is intended to reduce any risk.”

Additional symptoms of monkeypox include chills, swollen lymph nodes, and muscle aches. A more complete list of symptoms is available on the CDC’s website.

Reynolds notes that while monkeypox is rarely fatal, it can lead to hospitalizations in some instances. “Monkeypox, unlike smallpox, has a very low risk of severe complications or deaths, but it can be painful…particularly depending on where those pox are located,” she explains.

Individuals who are living with HIV/AIDS are at a significantly higher risk for severe complications, as well as death. “It is critical that folks that do have immunocompromised situations with HIV status are aware of their personal risk, and take the appropriate additional precautions,” Reynolds adds.

For individuals who require hospitalization, there are antiviral treatments available in limited supply —- including a drug called Tecovirimat, which is primarily utilized for smallpox. Tecovirimant is known to be safe in humans, and is being prescribed to reduce symptoms and overall pain in monkeypox patients.

Stopping the spread: Vaccines, messaging and stigma

Reynolds notes that monkeypox differs substantially from Covid-19 in that symptoms in exposed individuals may present as many as three weeks after contact with an infected person.

She admits that this extensive period of uncertainty before symptoms develop (and before a test would come back positive) will likely make slowing the spread of monkeypox difficult — as it would require long quarantines that could put many Americans’ fragile employment status at risk.

Compounding the issue is that across much of the U.S., there appears to be little appetite for additional health-related measures and restrictions after more than two and a half years of a global pandemic.

“It’s going to be more challenging to prevent the spread for those reasons,” offers Reynolds.

On Aug. 11, the CDC unveiled new guidance that lifts the recommendation for individuals to quarantine after possible Covid-19 exposure, even as daily deaths from the ongoing pandemic hover at around 500 per day — more than 3,000 per week.

Adding to these other sources of difficulty in preventing the spread of monkeypox, Reynolds notes, is that sex is often not addressed only in American society — particularly with regards to the risks of possible infection and disease.

She says that the initial reaction to the monkeypox virus in the media and public sphere bears some resemblance to the early days of the HIV/AIDS crisis.

“There’s a spectrum of concern —[and there’s a] concern that the virus is contracted through some relatively easy manner — like through a bathroom or some other object, which has not been the risk for monkeypox, nor was it for HIV,” explains Reynolds.

Additionally, there is a view among some members of the public — exacerbated by some media coverage — that monkeypox is only a real threat for members of the gay community.

“Again, that’s not necessarily true. It depends on who may be exposed, and in an intimate situation with another individual,” Reynolds says.

Tracing back to the county’s earlier response to Covid-19, Reynolds recalls a gap in language where some individuals did not identify people they had recent sexual activity with as “intimate” relationships, which hampered the ability of public health officials and contact tracers to obtain the most accurate information.

“Having that language to be able to begin to talk about sex and that skin-to-skin exposure comfortably is going to be really important,” says Reynolds. “And then individuals [need] to begin to think about their [personal] risk on their own.”

Ultimately, Reynolds recommends that communities that are at-risk — including men who frequently have sex with other men, people with HIV/AIDS, and people who have multiple or anonymous sex partners — should strongly consider making choices in the short-term that lower their risk level.

That includes the possibility of abstention from sexual activity for the time being, or even just sitting down with prospective partners and having an honest conversation about the risk associated with monkeypox — and discussing possible exposure to the virus.

Update Aug. 20: On the evening of Thursday, Aug. 18, Dean Gary Pierson sent out a message to students from university president Brad Baca. That message is excerpted below:

“MPV is not known to linger in the air and is not transmitted during short periods of shared airspace, making it very unlikely to spread in classroom settings. At this time, most students are considered to be at low risk.

Western’s COVID Management Response Team and other campus partners continue to build upon our strong relationships with our public health colleagues at Gunnison County Health and Human Services (HHS) to ensure we continue to make the best decisions for our campus community and coordinate evaluation and management strategies.”

Additional information on preventing monkeypox can be found on the CDC’s website.