As Colorado Parks and Wildlife prepares to reintroduce wolves, a public meeting on the issue will be held from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Jan. 25 in the Western Colorado University Ballroom, including a public comment period beginning at 10:55 a.m. Public comments can also be made virtually throughout the month of February.

By Courtney King

On the eve of the Winter Solstice, while I was staying at a home outside Gunnison, I was awoken by the howling winds outside. That sound, as well as my memories of the sunset view from the cabin, inspired a thought — what if instead of the howling wind, I were to hear the howling of a wolf pack?

A few days prior, I had sat around the fireplace with some new friends and discussed the challenges with living well outside of Gunnison. As it is, life in town during this time of year is already (largely rightfully) portrayed as a constant struggle against nature.

My friends all had experience working either with or for ranchers, as either ranch hands or as representatives of land management agencies and organizations who encountered ranchers as a part of their daily work.

That evening had begun with a conversation about regenerative agriculture and perceptions of the local ranching community, and so it was no surprise that by the end of the night, we were discussing the topic that always seems to come up (at least in my circles, which are admittedly small and often overlapping in the academic, wildlife, and outdoor realms): wolf reintroduction.

Those living in western Colorado at the time will likely remember voting on wolf reintroduction in the Nov. 2020 statewide election. Ballot Initiative 114 had passed — by the slim margin of 50.91%, and with most of the western slope in opposition — mandating Colorado Parks and Wildlife to return wolves to the centennial state by the end of 2023.

It was an exciting time to be involved in Colorado’s direct initiative process, where qualified proposals go directly on ballots for citizens’ approval, instead of needing to be submitted to the legislature for passage.

I had first learned of this process when taking a course on trapping wildlife — or rather, the language and optics surrounding trapping wildlife — on the East Coast. I was surprised to learn that certain “box” or “cage” traps were only banned in two states: Massachusetts, where I was taking the course, and out in Colorado.

Scheduled to move to Gunnison in the near future, I asked the wildlife biologists leading the course why these traps had been banned in Colorado, a state I hadn’t yet visited but knew was renowned for its ample hunting opportunities.

The answer given — whether rooted in opinion or fact I was unsure, was that advocacy groups had persuaded the state’s still-growing urban population that these traps were inhumane and should be banned, with the significantly smaller population of wildlife trappers who were most impacted by the rule left to face that decision’s consequences.

Wolves on the ballot

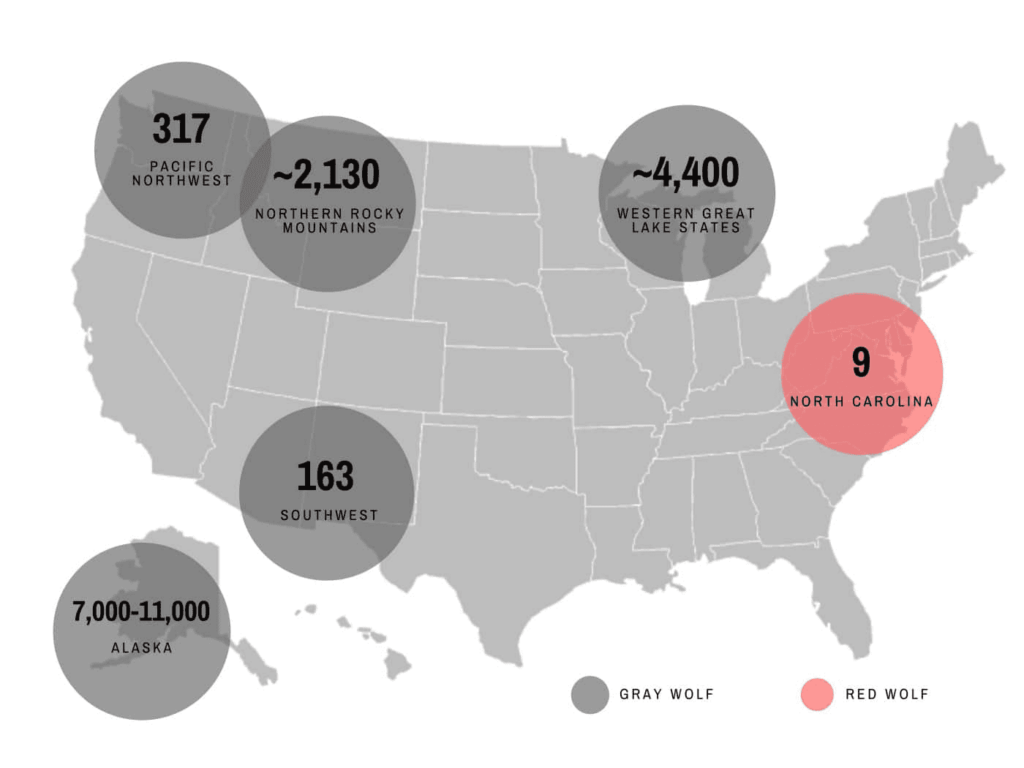

Several years later, that same rural-urban divide, and the accompanying attitudes, would come into play regarding wolves — one of our nation’s most charismatic predators — and likely America’s most controversial animal, particularly out west and in Alaska where the bulk of the nation’s wolves live.

In detailing the history of Ballot Initiative 114, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) notes that a citizen-led group known as the Rocky Mountain Wolf Action Fund had begun circulating petitions related to wolf reintroduction in the summer of 2019, more than a year before the vote took place.

For an initiative to be put on a ballot, petitions are required to reach a certain number of signatures. That number differs annually but is essentially around 125,000 — quite a small proportion of the state’s more than 5,750,000 total residents.

Interestingly, there doesn’t appear to be any requirement that these signatures be obtained from a broad geographic range, and thus it’s clear that a base of support from a large urban population could more easily push an initiative onto the statewide ballot.

Of course, that doesn’t guarantee an initiative will be passed, and wolf reintroduction became a popular topic of debate in the fall of 2020. Perhaps debate is not even the right word, however, as it seemed like these conversations really served as echo chambers for those who already held the same views — and took solace in that fact.

Nevertheless, the subject of wolf reintroduction had been discussed in Gunnison and similar communities across Colorado well before the 2019 petition saw the light of day.

At the same time as wolf advocates took to the media to extol the virtues of wolves within Rocky Mountain ecosystems, Idahoan ranchers were working to make it easier for wolves to be killed (they succeeded, and a 2021 law permitted hunters, trappers, and the state itself to kill up to 90 percent of the state’s wolves, more than 1300 animals).

Around this time, the Western’s student chapter of The Wildlife Society was contacted by Defenders of Wildlife, an environmental advocacy organization whose logo features a howling wolf in front of a picturesque southwestern landscape.

DOW was promoting various efforts and resources related to wolves, including those designed to help ranchers and wolves coexist, and the advocacy group asked if the students would be willing to facilitate a Gunnison community meeting for those with differing views on wolf reintroduction to engage in open dialogue. Sounds healthy and productive, right?

But, as you, the astute reader, might have anticipated the event quickly devolved. The commendable intention of finding common ground between the ranching community and supporters of wolf reintroduction quickly turned into an all-out verbal brawl.

One side was ostensibly defending the rights of wildlife, while the other had livestock in their proverbial care, and the meeting served as a fighting ground where individuals vehemently stated their views and became progressively more defensive of them — at least, those who didn’t ultimately walk out early.

The student organization, on the other hand, left feeling somewhat duped by those who had encouraged them to provide the space for such a volatile conversation without providing a mediator or other conversational guardrails.

I wasn’t at that meeting, but hearing about it from a former Western student reminded me of a similar event that had occurred when I lived on Cape Cod, out in Massachusetts.

Following the tragic death of a surfer, a town hall meeting was convened, in incredibly New England-like fashion.

The meeting was intended for shark researchers and town administrators to answer residents’ questions and begin finding and navigating a shared path forward. Of course, with time allocated for a public discussion period, the meeting made for a rather interesting listen.

While this meeting had a degree of order — with residents lining up to a microphone to ask questions and speak their minds — the points raised were followed by a chorus of cheers and boos that highlighted a divided room.

Many attendees noted that this was the first time in decades a shark had killed a human, and added that humans were the ones encroaching on the sharks’ habitat. Those attendees offered potential action steps, such as not surfing in the fall (the most common time to see sharks, and unfortunately also the time known for the best waves).

Others noted that the area’s fishing industry leads seals close to the shore, luring in sharks. While this is a valid point, the solution raised (“culling,” i.e. killing, seals) is not legally allowable due to the Marine Mammal Protection Act, passed in 1972. As the town administrators were forced to reiterate, the only way seals could be killed was if this federal act was repealed after decades on the books, a nearly impossible proposal.

Returning wolves to the woods

Returning to our controversial land predators: gray wolves, the case is far murkier. Colorado has now gone more than eight decades without wolves (although recently, some wolves have trickled down from Wyoming into northern Colorado) — and the potential direct impact on humans, in the form of animal loss in domestic and livestock contexts, is far greater than with sharks.

Unfortunately, emotions and preconceived notions have substantially interfered with the science, and wolf reintroduction may not have nearly as much impact on Coloradan’s lives and livelihoods as some have been led to believe.

One of the most important things people should know is that CPW is directed to “provide fair compensation for any losses of livestock caused by gray wolves.”

Of course, there are instances where proving a livestock fatality is impossible — with calves who have just been born and are not yet tagged, for example — but the compensation program, which can grant up to $8,000 per confirmed kill, is nevertheless valuable to decrease the overall losses of ranchers and farmers.

Nonetheless, it’s clear the state wildlife agency expects some rogue individuals to take matters into their own hands. On their website, CPW outlines the penalties for killing a wolf on a frequently asked questions (FAQ) page, stating, “We strongly encourage people to be ethical and follow the law.”

Although the agency denies it, grumblings have indicated that many employees in the agency (at least in areas where wolves are likely to be released) aren’t thrilled with the associated burdens that accompany wolf reintroduction.

The Draft Management Plan even states that CPW lacks the staffing and financial resources to undertake the lengthy National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) compliance that would be required to release wolves on federal land, so the 30 to 50 wolves set to be released starting in 2024 will instead be released on state land — and private land with the permission of landowners.

Ultimately, and no matter how the agency’s personnel feel, CPW will shortly be responsible for introducing and subsequently managing wolves, undoubtedly expending much of their limited staff and resources otherwise dedicated towards other species (non-hunted species, that is, as the funds generated from hunting and fishing are not fair game).

They’ll also have to shoulder the blame — rhetorically and financially, for human-wolf conflict, which will most likely take the form of livestock kills, which have already been confirmed in northern Colorado with the migratory population coming down from Wyoming.

And so, in response to their own question posed on their own website: “Who will be responsible for responding to damage claims/human health and safety issues and how will the costs be covered, including wages?,” The agency offers the blunt statement, “CPW will respond.”

And finally, Colorado Parks and Wildlife will be responsible for answering one of the major questions on everyone’s mind since the passing of the ballot initiative — where will the wolves go?

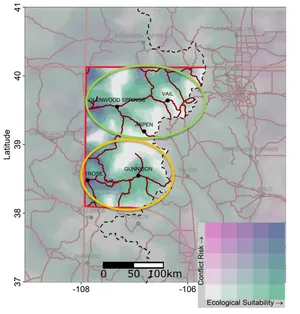

As Gunnison residents learned a few weeks ago, the answer (well, in part) is here! Specifically, the agency’s Draft Management Plan lists the Highway 50 corridor between Monarch Pass and Montrose as one of the proposed release locations, along with an area to the north surrounding, and between, the towns of Vail, Glenwood Springs, and Aspen.

The wolf debate rages on

Naturally, the potential for wolves to be released near Gunnison sparked discussion everywhere, but perhaps most notably on what has become a sort of makeshift, modern town square — Facebook Marketplace.

Some chimed in to offer that wolves are meant to be here, and that we should adapt to their presence as a fundamental part of the ecosystem.

One poster shared a story detailing how ranchers in Montana dealt with the influx of predators long extirpated from Western memory – including teaching their cattle how to defend themselves.

That comment reminded me of sentiments expressed by a CPW employee I spoke with a few months back; originally hailing from South Africa, he remarked how unlike in his home country, most of us in the United States have hardly had to learn to live with predators.

For those in the ranching community, becoming reacquainted with doing so likely means expending extra effort towards protecting one’s livestock, an additional strain at a time when water scarcity and other factors are already stressing ranchers.

The Facebook comments were full of concerns regarding safety of both livestock and humans, and tied back to the overarching sentiment that “We didn’t vote for this, so we shouldn’t have to deal with it.”

And while the majority of Gunnison county residents did in fact vote against wolf reintroduction, the population who voted for (43 percent) was not insubstantial, and the social-ecological modeling map study used to determine possible release locations throughout Colorado did take social acceptance into account.

Some of the areas deemed to have the most suitable wolf habitat had less than 30 percent support for reintroduction, and thus largely fell out of consideration for wolf releases.

Despite the importance of ranching in Gunnison’s history, culture, and economy, numbers make it clear that the opposition to wolf reintroduction isn’t all coming from ranchers themselves, but likely includes other members of the community speaking up on their behalf.

For some time, ranchers and other individuals who are dedicated to retaining the ranching lifestyle have largely been framed as a monolith against wolf reintroduction, but we know that is likely untrue.

That perception is reflective of preexisting divisions within the community, which likely make it harder for those in the agricultural community who might otherwise be accepting of wolf reintroduction to have their real voices heard.

In this instance, they may feel forced to decide whether they’re on the side of conservationists (often perceived as outsiders) versus that of their close neighbors and fellow ranchers. A particularly difficult “choice” to be forced into as many ranchers cite the ability their profession allows them to enjoy and act as stewards of the land.

Fortunately, while the agency can’t guarantee their final plan will please everyone (or anyone, for that matter), they are at the least obligated to open a public comment period and consider the entire spectrum of resulting opinions.

In Gunnison, an open meeting will be held from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Jan. 25, in the Western Colorado University Ballroom, and comments can be made virtually throughout the month of February.

Based on the aforementioned Defenders of Wildlife meeting, one could not be blamed for fearing that the upcoming public comment event in Gunnison could devolve into chaos, like the Massachusetts town hall on living with sharks.

But what ultimately shined through in that town hall, however, were means of moving forward. In that particular case, those means took the form of stop-the-bleed courses, the proliferation of emergency communication devices, and other procedures that made the community safer.

Just as that town couldn’t depredate seals, individuals living on the Western Slope will be unable to legally kill wolves when their population numbers are low, and to prevent them being brought here in the first place. In all likelihood, dozens of wolves will freely roam the Western Slope within a couple of years.

CPW is hosting additional meetings across the state for potentially impacted communities, with future meetings to be held in Rifle (Feb. 7, 8 a.m.), Denver (Feb 22, 8 a.m.), and virtually (Feb. 16, 5:30 a.m.).

Hopefully, those opposed to wolf reintroduction in town and elsewhere can feel that their concerns are heard and met —and move beyond the initiative’s passing and into developing feasible strategies for mitigating threats to livestock and pets.

Down the line, the final Management Plan is set to be released on April 6, and the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission is set to take their final vote on the plan May 3 and 4.

In the meantime, the public meetings and comment periods are likely to stir up debate around wolves greater than Coloradans have experienced so far.

One thing is for certain: plenty of howling — for or against the plan — is sure to come.

The full public meetings and wolf reintroduction plan timeline:

- Jan. 19: Colorado Springs, 8 a.m.

- Jan. 25: Gunnison, 8 a.m.

- Feb. 7: Rifle, 8 a.m.

- Feb. 16: Virtual via Zoom, 5:30 p.m.

- Feb. 22: Denver, 8 a.m.

- April 6: Colorado Parks and Wildlife set to present final plan to Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission

- May 3-4: Commission set to take final vote on the plan

More info on the meetings can be found on CPW’s website.

We already have coyotes, bears and mountain lions that kill our wildlife…We do not need an apex preditor to join in and kill deer, elk, livestock and the Gunnison Sage Grouse..The grouse are protected and an easy meal for wolves. They just stand there as I walk by. Not much of a challenge for a wolf pack…

Thanks

I suggest that that everyone who voted for wolf restoration be the ones who pay for livestock that are harmed by the wolves…Why should anyone else be responsible?

They want them here, then they pay for it!