Colorado Parks and Wildlife held a public meeting on Wednesday, Jan. 25 in Western’s University Center Ballroom to discuss the topic of wolf reintroduction.

You can watch the recorded meeting in its entirety on YouTube. Public comments can be made via CPW’s website through Feb. 22, and the full draft plan can also be read on CPW’s website.

After a presentation from Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) staff, several dozen members of the public had a chance to provide input in front of members of the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission.

The majority of commenters came from ranching and agricultural production backgrounds. The hunting and outfitting community was also well represented. Commentors from these groups expressed concerns about reintroduction, encouraging agency restraint and flexibility in management — including the right to kill wolves that pose problems for humans, predominantly in the form of livestock depredation.

Additionally, a number of wildlife and animal advocates spoke in favor of the wolves — citing moral and ecological rationales — and against the possible hunting of wolves mentioned by CPW’s draft plan in a prospective phase four of wolf reintroduction .

The CPW reintroduction phases are defined as:

Phase one: Endangered classification — Wolves will be introduced 10-15 at a time from northern Rocky Mountain states over the course of three to five years until at least 50 wolves are observed for four consecutive winters, at which point the state will reclassify wolves to phase two.

Phase two: Threatened classification — After moving on from phase one, wolves will remain in the second phase until their population in Colorado reaches 150 in successive years, or 200 in any individual year, when they will be moved to phase three.

Phase three: Non-game species classification, removed from the state’s endangered and threatened species list — wolves will remain in this phase under the current draft plan until parameters are established for the fourth and final phase.

Phase four: Game Species — This classification would make it legal for recreationists to hunt wolves, should this phase ever be formally established and come into play down the line.

In many ways, the meeting raised more questions than answers, but we’ll attempt to guide you through the key points — questions raised, comments expressed, and the next steps moving forward to the plan’s eventual passage in May.

Here’s what you should know:

Takeaway #1: Some compromise can be found in the use of nonlethal means — and even lethal means, to reduce damage to agricultural producers and overall human-wolf conflict.

A number of ranching advocates and wildlife boosters alike spoke to the importance of promoting and funding such efforts, including the use of propane cannons, fox lights, cannon shells, improved education, and other methods of conflict reduction, which could include physical or virtual fencing — like special fencing used in Minnesota to protect livestock from the state’s wolf population.

It is generally agreed that the use of nonlethal methods will take precedence before lethal methods are used. Expect more details to come on specific mitigation strategies in future CPW meetings this winter and into the spring.

At the meeting, some wildlife advocates even spoke of supporting lethal means as a necessary means to reduce conflict if and when it arises. However, funding for these measures was a frequent topic, which leads into the next takeaway…

Takeaway #2: Lack of designated funding and other resources loomed large over the meeting.

As CPW, staff, commissioners, and commenters frequently noted, Proposition 114 is an unfunded mandate, and there is widespread concern about whether the state agency has the resources and personnel to respond to wildlife kills and provision the materials and support needed by ranchers and others impacted by wolf reintroduction.

The real possibility remains that other CPW programs will be compromised to fund initiatives directly related to wolf reintroduction. As of yet, there is no legislation in the young session of the Colorado state legislature to remedy this issue, and also no real estimate on what the wolf reintroduction may cost.

Many ranchers expressed concerns about CPW’s ability to swiftly respond to wolf depredations of livestock, citing remote ranches that require multi-hour UTV and horseback rides to access.

Additional concerns were raised about the timeline of depredation compensation, with one commenter suggesting a more stringent 60-day remuneration window.

Takeaway #3: CPW and the ranching community agree — the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) utilizing the Endangered Species Act’s 10(j) rule is critical to effective management.

The federal rule will classify the wolves as an “experimental, nonessential” population, and will allow for lethal taking and other measures taken against wolves which could help reduce livestock or ungulate depredation. Overall, the rule could make reintroduction efforts, which many ranchers already view as a huge compromise, more socially palatable on the Western Slope.

Using such measures is critical to the impact-based management philosophy that CPW is currently utilizing, which prioritizes education along with a number of tools to be used on a case-by-case basis as required — up to and including lethal taking.

Takeaway #4: The draft plan’s current program for compensating agricultural producers for depredations leaves many wanting more — and the issue of indirect losses complicates matters.

CPW’s proposed monetary compensation limit of $8,000 is vexing for ranchers, who cite prized horses that are worth more than double that.

Depredation confirmations will be made by CPW personnel under a preponderance of evidence standard (better than 50 percent chance it was a wolf kill).

Additionally, animals critical to their operations, such as trained herding dogs (which can be worth many thousands of dollars) would not be covered by the draft plan.

Another issue is that of indirect loss which would be difficult to compensate for — including added stress and lost weight in livestock, as well as lost land and foraging area as ranchers shrink the effective size of their ranches in an attempt to protect their animals.

Expect updates to this portion of the plan as it pushes towards completion.

Takeaway #5: Impacts to wildlife species remain largely unpredictable and divisive.

Several commenters raised the issue of the Gunnison sage grouse, a federally threatened bird with a population of less than 3,000 individuals (more than 85 percent of which live in Gunnison County), which has been the subject of conservation efforts in the community for more than two decades.

The impact wolves, as apex predators which can consume a wide range of animals (although they mostly prefer to eat ungulates) may have on the threatened grouse is largely unknown, but certainly worth watching.

At over 280,000 animals, Colorado’s elk population is currently the largest in the world. As it stands, hunters legally kill about 50,000 elk each year, Advocates for a number of wildlife groups and outfitters, including the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (RMEF), expressed the concern that a burgeoning wildlife population could strain the elk population, and lead to decreased opportunities for hunters, and potentially diminished business for hunting outfitters.

For their part, wolf advocates argue that restoring wolves to the land benefits overall ecosystem health. Those benefits can include killing sick and other unhealthy prey from the population (and forcing them to congregate in smaller groups, which can lessen the spread of chronic wasting disease), providing a check on overpopulated ungulate species — boosting over-foraged plant life and benefiting other animals, and redistributing nutrients via the carcasses of animals they kill, which provide foods to a number of species.

Another issue that was raised is that of the Mexican gray wolf, the rarest subspecies of wolf in North America. Currently, the Mexican gray wolf is listed as critically endangered with an estimated population of roughly 160 individuals — the result of a 1998 USFWS reintroduction to a recovery area in western New Mexico and eastern Arizona.

Some raised concerns that the reintroduction of gray wolves to Colorado could have a diluting genetic effect on Mexican gray wolves, should the species interact. In order for that to happen, wolves would need to travel hundreds of miles south and across state lines. Of course, that isn’t unheard of, as wolves reintroduced to the northern Rockies have made their way into Colorado, and were confirmed in the northern portion of the state as early as 2004.

Additionally, more than 900 other species reside in Colorado and are managed by CPW, including dozens on the state’s threatened and endangered species list.

Takeaway #6: Many in attendance want to see CPW work more closely with the federal agencies that manage the vast tracts of land where wolves will likely soon roam.

A number of commenters, largely from the ranching and hunting vantages, raised the issue of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), a federal environmental law intended to review major actions on federal lands for ecological impacts.

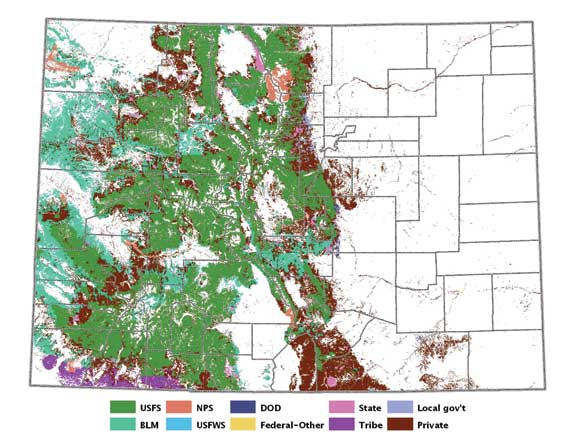

Due to the shortened time frame of the required wolf releases, the NEPA process has not been initiated, and is instead being circumvented by CPW planning to release the wolves on state and private land. Of course, large portions of the Western Slope are federal lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, and U.S. Forest Service — including prime wolf habitat.

Though their release will not take place on federal land, it’s inevitable wolves will roam federal lands soon after their release.

But due to the condensed time frame mandated by the ballot initiative, initiating NEPA would likely complicate matters further. A full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) under the law typically requires several years at a minimum, time CPW simply doesn’t have with the end of 2023 deadline.

What is more likely is expanded coordination and communication between CPW and its federal partners as the reintroduction approaches.

Takeaway #7: The prospect of hunting wolves is top of mind for animal rights and wildlife advocates, and is serving to validate that community’s reintroduction fears.

Many animal rights advocates expressed dismay that CPW would make mention of a possible future where wolves could be hunted in Colorado, making use of the refrain: “Murder is not management.”

While phase four is largely nebulous and likely many years away, it was a consistent focal point throughout the public comment period for those in the pro-wolf camp.

One woman expressed that CPW’s draft plan made her question if her husband — who voted against the wolf reintroduction for fear that the effort would be botched, and ultimately lead to more animal suffering — would be proven correct.

For CPW, the introduction of phase four allows them internal flexibility should the population of wolves in the state balloon and cause major headaches for the agency.

It also signals to ranchers and others against or cautious about the reintroduction that there will be some sort of backstop in place to slow or halt the return of wolves, should it be needed.

Watch for updates to phase four as the public process continues heading towards a final plan in May.

Takeaway #8: CPW is not setting any population goals for wolves. In light of this, what is the right number of wolves for Colorado?

CPW was very clear on Wednesday that it was not setting any population goals with its outlined metrics, and that the benchmarks given were for the purpose of sating the ballot initiative and moving wolves off the state’s endangered and threatened species list.

A wide range of opinions were expressed at the public comment session — ranging from encouraging CPW to do the bare minimum legally required (CPW staff noted that a theoretical population of 86 wolves would have a 0 percent chance of being extirpated, according to their models) to pushing for a population of hundreds of wolves — citing studies from the late 1990s and mid 2000s that found Colorado to be prime prospective wolf habitat, and put the viable wolf population in the 400 to 700 range.

One important caveat: Colorado has added more than a million new residents in the last 20 years (the population today is roughly 5.5 million) although much of that growth has come on the Front Range, which won’t be considered for reintroduction, although wolves may choose to migrate there.

Ranchers and others cautious about reintroduction emphasized that the ecological carrying capacity for wolves is lower from the number that can be sustained sociologically, and noted that Colorado has a larger population that other wolf-bearing Rocky Mountain states Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming put together.

That said — Minnesota, which has a very comparable human population, has about 2,700 wolves, and more than 80 percent of Minnesotans support maintaining the state’s wolf population.

Out west, both Oregon (4.2 million people and an estimated 175 wolves) and Washington state (7.7 million and about 200 wolves) are fairly similar to Colorado in their demographics and lifestyles and boast significant wolf populations — although not without issue.

One thing is for sure: The issue of wolf population is not going anywhere.

Takeaway #9: Ranchers want CPW to share data about wolf populations for risk mitigation purposes.

A number of ranchers raised the prospect of having CPW share collaring data with agricultural producers in order to provide awareness and aid mitigation efforts.

Per the agency’s draft plan, CPW plans to collar all released wolves and at least one, if not two, members of packs as wolves establish themselves in the wild.

Look out for more information on data sharing moving forward.

Takeaway #10: For better or worse, Colorado stands alone as a unique case — and the nation is watching.

The state’s effort to reintroduce wolves constitutes a number of firsts — the first predator reintroduction spurred by a ballot initiative, as well as the first to be headed by a state agency.

CPW’s Commission, CPW staff, the Stakeholder Advisory Group, and the Technical Working Group (TWG) have cumulatively poured many thousands of hours of work into crafting the draft plan — and were commended by nearly all in attendance for their collective efforts and diligence.

Additional public meetings and wolf reintroduction plan timeline can be found below:

- Feb. 7: Rifle, 8 a.m.

- Feb. 16: Virtual via Zoom, 5:30 p.m.

- Feb. 22: Denver, 8 a.m.

- April 6: Colorado Parks and Wildlife set to present final plan to Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) Commission

- May 3-4: Commission set to take final vote on the reintroduction plan

More info on the meetings can also be found on CPW’s website.