The wonderful world of bats

“There’s so many different impacts that bats have on the way we exist as a human society that people don’t even realize,” says Corinne Ryan, a Western alumna who defended her thesis and graduated with her Master’s in Ecology back in May 2023.

Colorado is home to 19 different species of bats, including the big brown bat, the hoary bat, and the spotted bat. These bats perform key functions in ecosystems, dispersing seeds from fruits, pollinating a variety of plants, and controlling pests. Sadly, bats are increasingly under threat from habitat loss and climate change.

“They contribute billions of dollars a year in pest control services, and that’s just their agricultural value alone,” says Ryan. Her personal favorite? The spotted bat, with its “massive, curved ears.”

“If you ever got eyes on one, you’d know,” adds Corinne.

Chiroptera, the mammalian order that encompasses the roughly 1,100 different bat species — more than one-fifth of all mammal species — remains significantly understudied, despite the many fascinating bat species.

The nocturnal critters, who often hide out in mines, caves, old buildings, crevices, and trees, often get stuck with a bad rap in broader western culture as dirty and scary creatures. They’re often linked closely with vampires and death, even though they’re largely harmless to humans.

In contrast, the Navajo think that bats act as bridges between the natural and supernatural worlds. Referred to as Jaaʼabaní, they believe that bats offered aid to humans and carried offerings from the gods down to Earth.

The threat of White-nose syndrome

Over the last two decades, White-nose syndrome, a largely fatal and extremely contagious fungal disease in bats, has been spreading west since its introduction to the United States in 2006. That relentless spread was one factor prompting Ryan to select bats as the subject for her Master’s in Ecology research project.

“WNS causes high death rates and fast population declines in the species affected by it, and scientists predict some regional extinction of bat species,” reads a National Park Service page on the fungal affliction, which is believed to have spread from Europe.

“It’s really important that we try to study and conserve these bat species that are impacted by White-nose syndrome,” said Ryan during her final project presentation back in May.

Approaching the end of her first year of graduate studies and searching for a research project that would have real, on-the-ground conservation applications, Corinne came across the draft plan for the Gunnison, Uncompahgre and Grand Mesa National Forests, known together as GMUG.

“One of the things that they specifically mention is that there needs to be more attention and research going towards bats,” relays Ryan. In 2017, she had spent portions of a study abroad semester researching bats down in Baja California Sur under renowned scientist Dr. Winifred Frick, the chief scientist at Bat Conservation International, a science and conservation nonprofit focused solely on bats.

Ryan’s field research

Project in hand, Ryan threw herself into learning about the biology, life history, and ecology of bats in the spring of 2022. By May, her field research sites were up and running — furnished with recording equipment designed to pick up bat calls.

Not long after, in July 2022, the day that many conservationists had feared came, and the fungus that causes White-nose syndrome was discovered for the first time in Colorado, appearing near the town of La Junta, about 60 miles east of Pueblo.

Hard at work at her field sites surrounding Gunnison and Montrose, Ryan set out to examine how different water bodies (bats typically live near water sources, because water provides habitat for the insects and other prey that they eat), elevation, habitat type, and human presence impact high-elevation bat species in western Colorado.

Her research utilized protocols developed by the North American Bat Monitoring Program on what is known as “passive acoustic monitoring.” Ryan notes that “Acoustic surveys are the most efficient, most straightforward, and least invasive method of surveying bats.”

Setting out her recording equipment at her study sites, predominantly located on U.S. Forest Service land between 7,500 ft. to 11,000 ft. in elevation, Ryan collected more than 55,000 bat calls between May and October 2022.

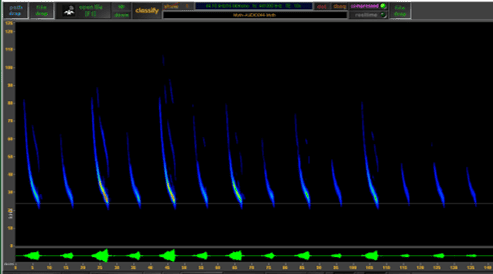

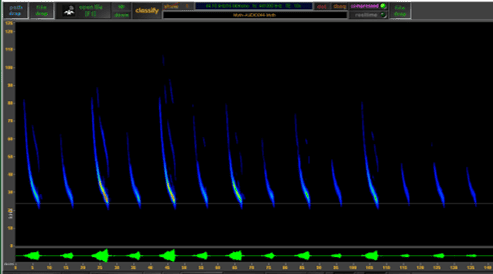

She plugged that data into the software SonoBat, an analysis system that identifies bat species by the sonogram (the visual image) of the sound recordings— with Ryan verifying the results by listening in to a portion of the call data. After taking a two-day course from Fort Collins-based Vesper Bat Detection Services, Ryan spent a month analyzing and verifying her sonogram data.

“You have to learn bat calls by sight, which is really interesting,” notes Ryan. “It looks really scary when you first get into it … but it actually ended up being fun because I’m a huge nerd.”

Identification complete, Ryan’s field research picked up 14 of the 19 bat species in Colorado. She then selected 10 species for further analysis based on their vulnerability to White-nose syndrome.

“That’s a double whammy for [those species]. They are affected by this really pervasive, super high mortality disease, and they exist at these higher elevations, so there’s really nowhere for them to escape to when it becomes hotter,” says Ryan.

The bigger picture

Ryan’s research confirmed the ongoing presence of four bat species at more than 10,000 ft., higher than ever before recorded: the small-footed bat, silver-haired bat, long-eared bat, and the Brazilian free-tailed bat. She also found several species of bats outside of their previously estimated range.

“It felt like a culmination of all of that hard work,” says Ryan, who was initially surprised by her findings — and had them double-checked by an expert (they held up under scrutiny).

Corinne’s work also found a scientifically significant relationship between human footprint and the small-footed bat, with the bat species occupying sites with lower human presence.

“This would indicate that this particular species really tends to avoid areas that have a high human footprint on the landscape, human alterations such as buildings, roads, and resource developments,” notes Ryan.

As with nearly all scientific research, her work raises a set of new inquiries for further study, especially considering the large gaps in human knowledge of bats. A prime example of this ignorance, Ryan explains, is that it’s still unknown if many of Colorado’s bat species migrate to escape the Colorado winter.

Notably, Ryan’s discovery of bats at previously unrecorded high elevations raises several distinct possibilities for the warm-blooded mammals that could inform the course of future research.

“There could be two basic explanations,” explains Ryan. “Maybe they tolerate high elevations better than we thought, because those areas do tend to be understudied. Maybe they were present there all along and we just didn’t know.”

The other explanation is that since “high elevations are warming; their thermoregulatory capabilities are less stressed in these high elevations now … so they’re moving up in elevation.”

Without previous and ongoing data, that question is nearly impossible to answer just yet, but the latter explanation could prove harrowing for bats as the climate continues to change, heating up Colorado’s summers.

One area Ryan would like to see targeted research on is the relationship between temperature and bat occupancy at the study sites, which would hopefully help researchers better understand how bats are faring in a warming world.

Unanswered questions and shifting perceptions

Additional research on bats in Colorado could examine what human alterations most impact small-footed bat populations, continue to study the impact of climate change on bats that are highly susceptible to White-nose syndrome, and determine the relationship between invertebrate populations (i.e., bat food) and bat occupancy.

Recently, biologists from the U.S. Forest Service have reached out to Ryan to notify her that they’re continuing the research at the sites Corinne had established. “That was really awesome, I was really hoping that would happen,” says Ryan.

Currently, Ryan’s working as a field biologist for a consultancy based out of Salt Lake City. Eventually, she hopes to polish and publish her research after a much-deserved cooldown from graduate school.

Altogether, Corinne is hopeful about the future of bat research and conservation — and about changing people’s negative perceptions of the 40 bat species across the United States.

“I think that in the next few years people will really start to get on board with bat conservation and the importance of studying [bats],” she concludes.

You can check out more Clark Family School of Environment and Sustainability (ENVS) research and conservation projects on the Western ENVS YouTube channel.